Abstract

The UN peacekeeping missions come into play when violence becomes overt. Peacekeeping comprises all those activities that tend to maintain lasting peace and facilitates efforts towards peace agreements to create room for peacebuilding. However, it has evolved in its structure, mandate, operations, and power (or power limitations) over time and is broadly recognized today in terms of first, second, and third-generation peacekeeping.

The following research paper analytically discusses the challenges, politicization, scope, and paradoxical approach towards peacekeeping and most importantly, the different facets of world politics that lead to the evolution of structure, mandate, and the scope of peacekeeping. It analyzes and brings to the light, with the help of case studies, how non-functional its efficiency has become due to the anarchy prevalent in the international system.

The paper would help readers analyze why the need was felt to move towards third-generation peacekeeping or if the very essence of peacekeeping has become limited to achieving strategic and socio-political goals and the aspirations of the West. Finally, the paper analyzes if NATO is establishing itself as the fourth generation of peacekeepers or if the emerging multi-polar world posits any challenge to peacekeeping missions of the UN and its mandate.

Keywords: Peacekeeping, Capstone Doctrine, UNOSOM, UNEF, UNAMIR, DPKO

Introduction

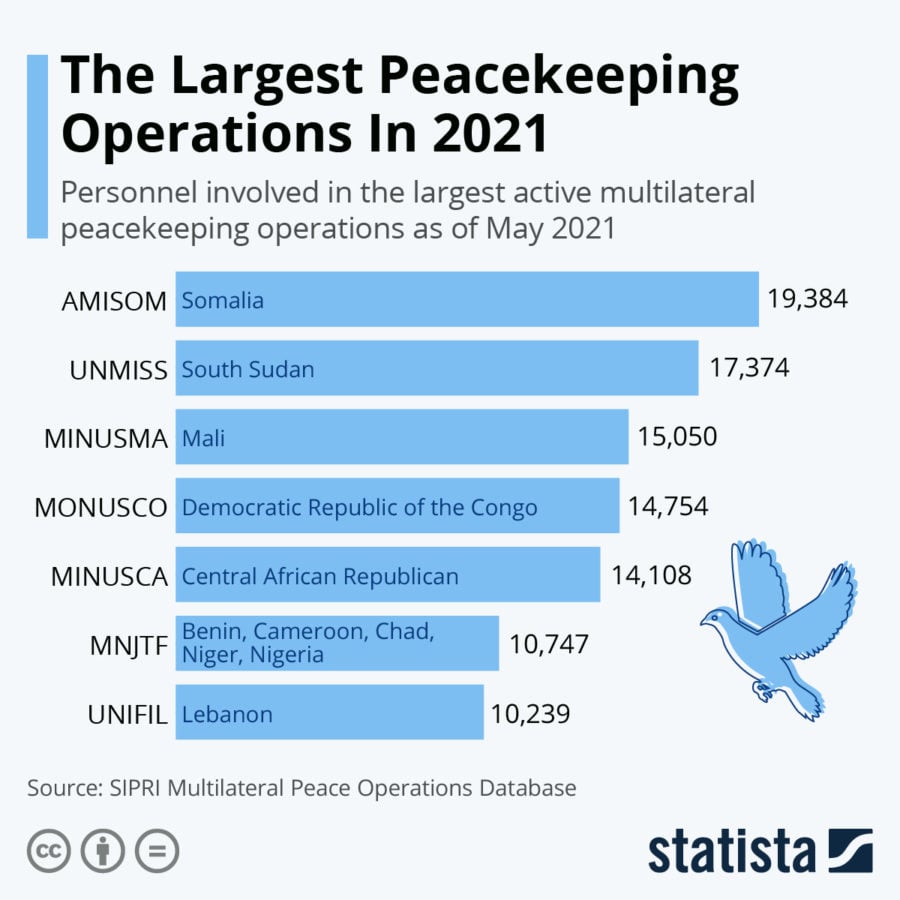

Since peacekeeping includes activities to maintain peace or establish it, it observes ceasefires and monitors security situations in the conflict zones, and reports back to the Department of Peace Operations and the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). Starting from United Nations Emergency Force (UNEF), there have been more than sixty peacekeeping operations, most notably in the Asian-African region and their funding exceeds the funding of the United Nations itself. Contemporarily, 13 peacekeeping missions of the UN—with a budget of $6.7 billion and 81,370 blue helmets (peacekeepers)—are active.

Goals of Peacekeeping

The goal of peacekeeping is to:

- Observe, monitor, and report the events in a conflict zone using patrol over-flights, static posts, and other technical means.

- Contain violence to prevent it from evolving into full blown war

- Limit the intensity, geographical spread, and duration of war.

- Consolidate and supervise ceasefire and support verification mechanisms to create space for reconstruction.

- Inter-position as a buffer and ensure confidence building measures among disputants.

First-generation Peacekeeping (1956-1990)

The contemporary structure of UN peacekeeping missions dates back to the formation of the United Nations Emergency Force, sanctioned by UNSC Resolution 1001 to secure an end to the 1956 Suez Canal Crisis between Egypt and Israel (Tandon, 2019). Its principles of impartiality, neutrality, commitment to the UNSC, non-use of force, and legitimacy were adopted as such in both the first-generation peacekeeping and second-generation peacekeeping. However, second-generation peacekeeping also adding political commitments to peacekeeping.

Formulated during the Cold War where the bipolar power structure of the world revolved around power politics, alliance making, deterrence, arms proliferation, the first-generation peacekeeping comprised lightly armed troops that would monitor merely ceasefires and buffer zones. The second emergency force, UNEF-2, was deployed following the ceasefire between Egypt and Israel after Yom Kippur War and to ensure the redeployment of Egyptian and Israeli troops across the buffer zone following the agreements of 18 January 1974 and 4 September 1975 (Wiseman, 1976).

The first-generation peacekeeping was not structured as we see it today as the world was divided along ideological lines – communism vs capitalism – and the world politics revolved around the international politics of the two rival states – the USA and the USSR. The conflicts that occurred during this time were limited in scope and intensity as compared to the wars before the Cold War and the intra-state wars following the Cold War. The peacekeeping, if any (in the true sense), was diverted to contain communism.

Second-generation Peacekeeping

With the dismemberment of the USSR and the emergence of a unipolar world structure, world politics also got structured across the domains of liberalism. With such an evolution, peacekeeping also became multicultural, multidimensional, and multilateral. The number of missions increased to 130 and the missions now employed a total of 1 million blue helmets.

Now, the traditional scope of peacekeeping evolved into a multiplicity of tasks including security, humanitarian, and political objectives. While its scope broadened in theory, in practice the humanitarian domain of peacekeeping was used significantly to ensure the transition of states towards democracy or liberalism in total.

With the unipolar power structure of the world, the dimensions of conflict also changed from inter-state to intra-state, or we might say that intra-state conflict intensified. With these dynamics, the legitimacy of the peacekeeping missions of the UN also became problematic. The UN peacekeeping missions failed abruptly while 2000 Tutsis were killed in a single day in an attack on a school, Ecole Technical Official, by Hutus in 1994.

Despite repeated warnings, the peacekeeping troops had preferred to escort foreign officials to the airport. The United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) proved to be the nadir of the subsequent failed UN peacekeeping missions despite showing some early successes in El Salvador, Namibia, and Cambodia, etc.

In the second-generation peacekeeping, the mandate was now transformed to:

- Strengthen the state to become powerful enough to sustain its own security.

- Facilitating the political process by promoting reconciliation to establish the legitimate and effective institutions of government.

- To provide for the safety of all UN-related and other international missions in a conflict zone so that they would work in a coherent manner in harmony.

Peacekeeping, however, failed abruptly to achieve any of its mandates. This can be seen from the case of Somalia where the UN Operation in Somalia’s (UNOSOM-I) intermittent presence could not prevent the succession of Somaliland from Somalia, or the insurgency leading to the autonomous Puntland in the north of the state.

Despite two brief spells of UNOSOM and a brief one-year period of United States-led United Task Force (UNITAF), neither the Islamists (Al-Shabaab militia) nor the insurgency in the south could be tackled. Although UNOSOM-II winded up the operation in 1995 (which started in 1992), it still faced casualties and failed abruptly. All these three missions were intended to provide humanitarian support to Somalia in the absence of any central government following the civil war initiated in 1988. Yet, the mandate of UNOSOM-II was modified in large to establish a democratic government in Somalia following the killing of 24 Pakistani peacekeepers.

Department Of Peacekeeping Operations

The success of second-generation peacekeeping, however, was the development of the Department of Peacekeeping Operations in 1992 that was sub-divided into the Office of Operations and the Office of Mission Support to provide logistical and administrative support to the peacekeeping missions of the UN. The Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) is charged with the development, planning, and management of peacekeeping operations as well as manages reimbursements for Contingent Owned Equipment (COE), letters of assist, and principles and guidelines for the peacekeeping missions of the UN, etc.

Third-generation Peacekeeping

The end of the 20th century marks the beginning of third-generation peacekeeping. Not only the rise of non-state actors has questioned the legitimacy of peacekeeping, but the peacekeeping missions of the UN were highly criticized for being highly politicized, ineffective, biased, and interest-driven (Kundi, 2021). In the post-9/11 period, states and regions within the ambit of the Global War on Terrorism felt viable enough to pursue their national interests, irrespective of the need of taking into account the international community.

Russia’s intervention in Georgia for the liberation of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, the USA’s occupation of Afghanistan in 2001 and Iraq in 2003 as well as NATO’s bombing of Serbia in 1999 in favor of Kosovo, interrogates whether there is any more need for already failed peacekeeping missions where pluralism and extreme nationalism rolls back globalization on one end and intra-state communal conflicts obstruct preventative diplomacy on the other.

Capstone Doctrine

However, to cope up with the deficiencies, a lot of reforms were practiced to improve third-generation peacekeeping. One such reform of 2006 was the “Peace Operations 2010” strategy which called for an increase in personnel, harmonization of conditions of service, improvement of the partnership agreements between DPKO and United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the African Union, and the European Union (“Peace Operations 2010,” 2006).

It also envisaged the development of clear and viable guidelines and principles for the UN peacekeeping missions. One such effort led to the formation of the Capstone Doctrine that sets the mandate for UN peacekeeping in the 21st century. The basic principles include peacebuilding measures as:

- Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration of Combatants (DDR) to provide former combatants with sustainable livelihoods.

- Mine action to regulate unexploded ordnance and mines to begin with the restructuring of the societies.

- Protection and promotion of human rights by monitoring and helping to investigate human rights violations.

- Electoral assistance (conduction of free and fair elections and the establishment of a legitimate state).

- Support to the restoration and extension of state authority. This involves the provision of operation support to state institutions, capacity building, political mobilization etc.

- Security Sector Reform (SSR)—peacekeeping is mandated by UNSC to be called for training, reform and restructuring of armed forces and police sector as well as legislative and judicial system.

As mandated by UNSC, NATO, by virtue of establishing transitional governments, has performed the role of peacekeeping but because governments were politicized, they did not represent the true essence of the democracy characterized by the “will of the people”. Hence, we see that the February agreement was between the Taliban and not the former Ghani government. The Taliban were seen as structural prevention to ensure the USA’s respectable exit from Afghanistan.

The UN peacekeeping missions in the aftermath of 9/11 are struck by numerous other problems that they fail to cope up with. For instance, in the case of Sierra Leone when the Revolutionary United Front was wreaking havoc on the state in the 2000s and the peacekeeping missions headed by India’s Major General Vijay Jetley crept into Freetown—the capital—leaving masses to the brutality of the revolutionaries (Ruggeri, Gizelis and Dorussen, 2013).

Also, the failure replicated when despite orders from the then secretary-general, Ban Ki-Moon, India’s Jetley refused to counter revolutionaries in the Democratic Republic Of Congo while insurgents took over Goma to the anger of Ban Ki-Moon (Oladipo, 2017). Both Kofi Annan and Ban Ki-Moon failed to remove India as a lead because India—the largest contributor to peacekeeping—threatened to drawback all its personnel.

In the New York Summit of 2015, there were intense negotiations between Obama and Ban Ki-Moon to equip peacekeeping troops with intelligence, modern equipment, and technology to the dismay of other developing states that are the major contributors of military personnel. They feared transforming peacekeeping to peace enforcement.

However, an ethos of “Responsibility to Protect (R2P)” was added in the second decade of the 21st century, and drones were deployed to monitor movements of the rebels as well as to verify the Rwandan claims that it was not supplying insurgent troops. Following the Goma debacle, it was allowed for the first time in history that military personnel may assume combatant form to subvert the threat of non-state actors. But the point of peacekeeping is highly contradicted here.

It is highly argued that peacekeeping is to monitor and maintain security situations and not enforce peace. Also, it becomes problematic as to whom to consider legitimate and this is where states politicize peacekeeping. The USA is helpless to act against Syria’s Bashar Al Assad while with the pretext of democratic realism, it claims to maintain peace in the world by destroying the peace in 2001, 2003, and again in 2011.

Similarly, UNSC members are polarized on various peacekeeping missions such as whether or not to impose sanctions on hostile government-backed Janjaweed militia in Darfur (Fleshman, 2010). While Russia and China back peacekeeping missions in Darfur, they oppose sanctions against the Sudanese government. The hostile or aggressive government becomes another challenge to peacekeeping as much as to decide on the legitimacy of non-state actors.

Both the money and personnel for the peacekeeping missions of the UN have expanded with the budget rising from $500 million at the end of the Cold War to $3.8 billion since 2000. But now the budget stands at $6.7 billion for the 13 contemporary peacekeeping missions. The number of personnel, however, has subsequently decreased from 1 million to 120,000 in 2015 to 81,370 in 2019.

In 2017, Antonio Guterres, as a later reform, suggested lowering budgets, increasing personnel, harmonizing the work of the Department of Political Affairs and the Department of Peace Operations (previously known as the Department of Peacekeeping Operations) to provide for more resources and options for broader peacebuilding measures, as well as to recognize emerging security threats and deploying preventative measures to curb the threat beforehand (“UN Reform Agenda,” 2017). This can be regarded as fourth-generation peacekeeping.

Conclusion

Whatever the generation, it is viable to understand that peacekeeping missions also operate in the anarchic international system where interest dominates politics and power drives the system. The role of peacekeeping in the 21st century is highly challenged by intra-state conflicts on one end and is also marred by allegations of malpractices and ineffectiveness on the other. The state continues to play a unitary and rational role in world politics, however.

References

- Fleshman. (2010). Darfur: an experiment in African peacekeeping. UN. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/magazine/december-2010/darfur-experiment-african-peacekeeping

- Kundi, M. (2021). Peacekeeping missions of UN: History and current challenges. Paradigm Shift. https://www.paradigmshift.com.pk/peacekeeping-missions-of-un/

- Oladipo, T. (2017). The UN’s peacekeeping nightmare in Africa. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-38372614

- “Peace operations 2010” reform strategy (2006). United Nations Peacekeeping. https://peacekeeping.un.org/sites/default/files/po2010.pdf

- Ruggeri, A., Gizelis, T.-I., & Dorussen, H. (2013). Managing Mistrust: An Analysis of Cooperation with UN Peacekeeping in Africa. The Journal of Conflict Resolution, 57(3), 387–409. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23414720

- Tandon, Y. (1968). UNEF, the Secretary-General, and International Diplomacy in the Third Arab-Israeli War. International Organization, 22(2), 529-556.

- “The UN Secretary-General’s reform agenda: what is it, why is it important, what does it address, and where is the human rights pillar? (2017). Universal Rights Group. https://www.universal-rights.org/blog/un-secretary-generals-reform-agenda-important-address-human-rights-pillar/

- Wiseman, H. (1976). United Nations and UNEF II: A Basis for a New Approach to Future Operations. International Journal, 31(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/002070207603100108

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please check the Submissions page.

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.