Algorithmic democracy is a concrete technological claim that presents the possibility of precision policy by making possible the rapid prediction of societal demands and the efficient deployment of public resources at a speed and scale far beyond what human administrators can achieve. The digital realm is replete with references like these. For instance, the Fire Department of New York’s FireCast algorithm, which automatically spots high-risk buildings prior to any fire starting, strongly shows how data-driven prediction can easily shift government from reactive to proactive operations. By detecting subtle patterns in complex or large datasets, machine learning paves the way smoothly for policies to move beyond “one-size-fits-all” solutions and facilitates services that meet the needs of distinct communities more effectively and quickly.

How Code Can Perpetuate Inequality

But here is the catch: precision and speed alone can’t properly ensure fairness. Algorithms are artifacts of human choices about which proxies to trust or which errors to prioritize avoiding. If these choices reflect past prejudice or structural neglect, the code itself can perpetuate injustice. Sadly, this has happened on countless occasions. Hiring systems, which are trained on biased historical decision-making data, can inadvertently repeat the past discriminatory patterns within the recruitment process.

One cautionary case of such prejudice is when women’s job applications were systematically downgraded by Amazon’s internal resume-screening tool, which was trained on the data of past applications and hiring decisions. Because the vast majority of past applicants and hires were men, Amazon’s sexist hiring algorithm automatically favored male-associated patterns and terms.

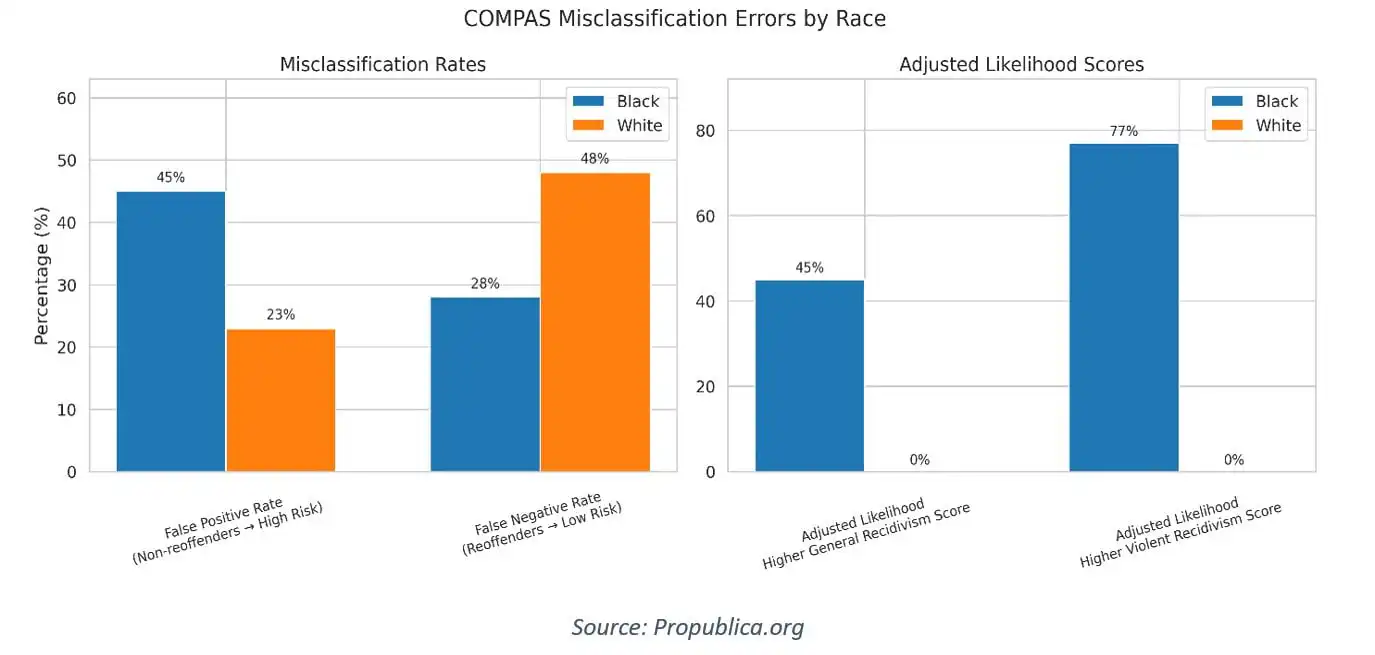

Florida provides another clear case of algorithmic bias through COMPAS, a proprietary risk-scoring tool used in the US criminal justice system to predict a defendant’s likelihood of reoffending. COMPAS outputs risk scores that influence decisions regarding bail, sentencing, supervision, and parole. Although the computer-run tool’s overall accuracy was similar for black and white defendants, it misclassified black defendants as “high risk” nearly twice as often as white defendants, even when they didn’t reoffend.

In contrast, white defendants, who later reoffended, were incorrectly predicted as “low risk” nearly twice as often as black reoffenders. Surprisingly, after adjusting for factors like age, gender, criminal history, and future recidivism, black defendants were still 45 percent more likely to receive higher general recidivism scores and 77 percent more likely to receive higher violent recidivism scores than white defendants.

These inherent injustices are hard to fix through purely code alone, owing to two foundational flaws. First and most importantly, there is no universal, math-based, clear criterion of fairness. Key quantitative fairness standards such as statistical parity, equalized odds, and equal opportunity can’t be mutually satisfied or compatible in many settings. Selecting fairness metrics is not a technical choice, but a public, value-laden decision regarding trade-offs.

Focusing on maximizing public safety by reducing false negatives can inadvertently lead to a surge in false positive rates, especially for vulnerable groups. Simply put, adherence to one formal fairness criterion may make another worse. Second, a substantial number of sophisticated models, including large neural networks and complex ensemble systems, are “black boxes” whose internal logic is largely incomprehensible to humans.

Centering Democracy in an Automated Age

There’s also a bigger structural risk to the political system. In a democracy, information and decision-making are decentralized, while a dictatorship keeps both tightly centralized. Totalitarian regimes of the twentieth century collapsed because human bureaucrats were not able to handle or process the massive amounts of data. With code-based governance, the dynamics will entirely change because algorithms thrive in data-saturated environments.

Consequently, automated systems facilitate extremely efficient centralized governments. The emergence of “AI bureaucrats”—governing finance, education, insurance, and even justice—raises concerns about a concentrated, automated authority that maintains a veneer of algorithmic fairness. But behind its seemingly fair façade beats a data-driven heart rife with racial and gender biases, geographic and religious prejudices, socioeconomic and political favoritism, and other entrenched systemic injustices. In concise terms, it hides value judgments and power imbalances.

Arrow’s theorem and the malleability of group choice remind us that outcomes depend heavily on institutional rules and information flows. Today, algorithms have become powerful tools for shaping those conditions. For democratic fairness to go hand in hand with algorithmic governance, the focus must be on a more institutional design and less on technical panaceas. Effective regulation must hold companies and institutions accountable for algorithmic harms.

Personal data should be used to help citizens rather than manipulate them. Meaningful transparency only matters if it is substantive. Instead of relying on opaque releases of model weights, it should prioritize clear documentation of training data and robust explanation mechanisms. Democracies should promote decentralization and community-driven systems in which decisions regarding fairness trade-offs are openly and fearlessly debated.

Finally, algorithmic systems may help in decision-making, but they can’t replace moral judgment or political accountability. Human beings possess an “inner moral compass” and a lived sense of justice that current machines lack. Behavioral interventions and nudges can be useful in certain contexts because people often rely on “mindless System 1 processes” that involve reacting quickly and automatically without conscious or logical thinking. However, the same mechanisms also open the door to psychological exploitation and deepen polarization when embedded in attention-maximizing platforms.

The enduring ethical concern is the risk of a “malignant transfer of fragility,” where elites enjoy the profits while ordinary citizens quietly bear the burden of opaque or systematic risks. Ensuring enforceable accountability and restoring genuine “skin in the game,” which means elites should also face consequences for the risks they create, is crucial to address this imbalance because fair governance depends not only on better predictions but also on institutions that enforce justice.

Conclusion

In short, algorithms can make governance more precise. However, precision without democratic control may come at the cost of fairness. Code-based governance should ensure that algorithms are governed by democratic institutions. They should be tested for bias, held accountable through liability, transparent when they affect rights, and integrated into civic processes that choose acceptable trade-offs. In the absence of these institutional safeguards, precision will too easily become an instrument of concentration instead of delivering justice.

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please visit the Submissions page.

To stay updated with the latest jobs, CSS news, internships, scholarships, and current affairs articles, join our Community Forum!

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.

Saqlain Haider Cheema is a columnist with a keen interest in global and political affairs