First Flight

Pan American World Airways or Pan American Airways (Pan Am), the symbol of American innovation, was the first American airline to fly transatlantic routes and conquer the aviation industry in an era when it was not even dreamed of. The airline, founded in 1927, was taken to its peak by Juan Trippe, who paved the way for its greatness for nearly four decades. The first Pan Am flight took off on October 19, 1927, leading the American aviation industry into endless possibilities.

The airline was not only a success story but also a cultural symbol for America. Unfortunately, its slow decline approached in the 1970s, until it went bankrupt in 1991. The last Pan Am scheduled flight, flown by pilot Mark Pile, landed on American soil on December 4, 1991. A legacy of more than 64 years ended and became a subject of study. This article entails the story of Pan Am and what led to its eventual decline.

The Era in the Making

The story of Pan Am is rooted in the United States of America of the late 1920s. The first airplane was invented just over two decades ago, in 1903, and the aviation industry, although glorified, was not understood, let alone captured. Congress passed the Air Mail Act of 1925, also known as the Kelly Act, which was the first step to commence and commercialize the aviation industry on a larger scale.

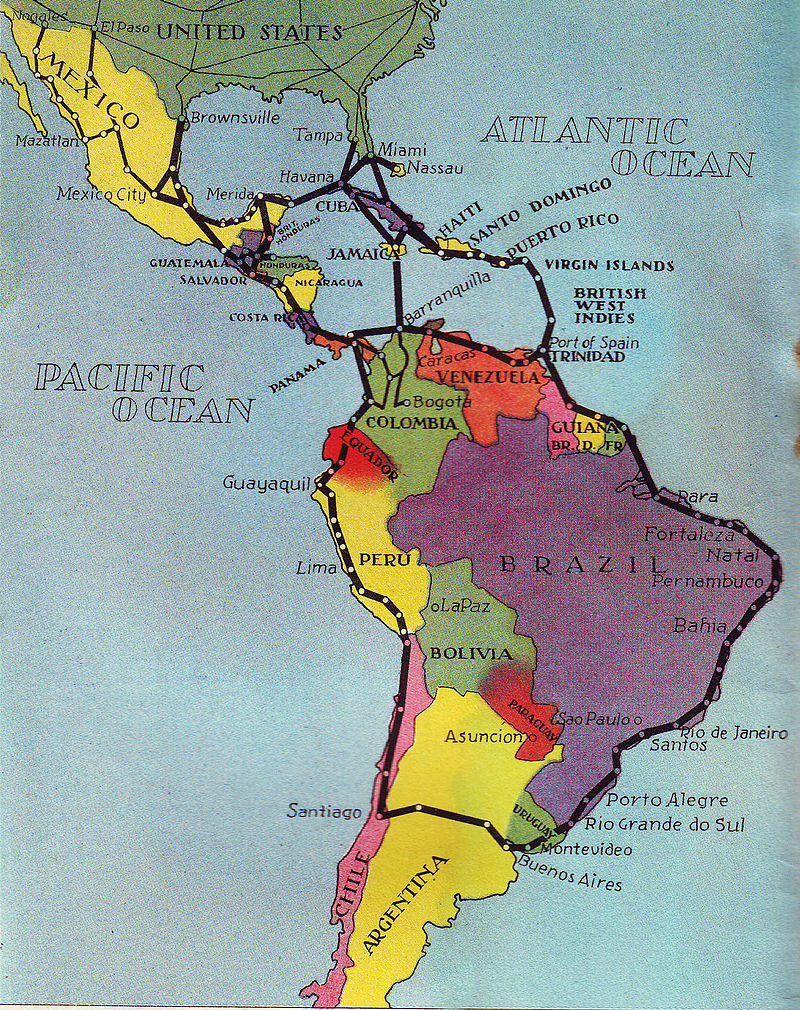

The act created an ecosystem for public-private partnerships, whereby private airlines would enter into contractual agreements with the government to deliver mail across the United States and beyond. At that time, three private companies were chasing a government contract to deliver mail to Latin America: Atlantic, Gulf, and Caribbean Airlines (AG&C), Aviation Corporation of America, and Pan American Airways.

Juan Trippe founded the Aviation Corporation of America, which merged with the AG&C to create Pan American Airways. Two things happened due to this merger. Pan Am received the government contract, and Juan Trippe became the airline’s president and general manager. He would then become the man who revolutionized international air travel and the mind behind Pan Am and its success.

The Rise of Pan American Airways

Juan first secured landing rights in South America and started killing regional competitors. One of the victims of his strategy was the Grace Shipping Company, which delivered mail by sea, and with whom Pan American Airways formed a joint venture. Apart from mail delivery, intrigue around air travel also increased around that time, and Juan knew his target customers—rich people who would happily spend money for the experience. Notwithstanding that the rich and elite were the only people who could afford air travel. These rich elites would also become the reason behind Pan Am’s survival and sustenance during the great depression.

Juan dreamed big for an aviation owner of that time, as he began visioning Pan Am’s stronghold over the world’s biggest oceans, the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. Pan Am’s aircraft collection would mostly comprise Skiroski flying boats since runways were uncommon. By late 1935, the first mail-carrying flight traveled across the Pacific Ocean, from San Francisco to Manila, Philippines.

In 1936, Juan’s dream became a reality as a passenger plane traveled in the Pacific. Following its success in the Pacific, Pan Am also found its way into the Atlantic Ocean. Competitors now had their sights set on Pan Am’s transatlantic routes. The airline was also successful during the Second World War, carrying people who wanted to flee Europe to America.

After the war, Juan attempted to monopolize Pan Am, the sole US airline to fly international routes. This insecurity resulted from increasing domestic airlines that aimed to fly international routes and foreign overseas airlines finding their way into the ecosystem. Trippe lobbied for the Overseas Airline Consolidation Bill in 1945, which advocated for a single US overseas airline to fly globally.

He also sought the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) to fly domestic flights. The bill naturally did not strike a chord with Congress, the media, and other competitors because of its anti-competitive motives in a newly expanding industry. Trans World Airlines was one of Pan Am’s competitors in the market and advocated against the bill to preserve its position in the market and its probability of becoming a success. The bill and the request to fly domestic flights were rejected for Trippe’s anti-competitive objectives, defeating his motivations for a monopoly. Nonetheless, Pan Am remained a major industry player.

The Jet Age

First invented in 1939 in Germany, the Jet plane was observed in WWI. However, it only became a part of commercial aviation in the late 1950s, with Pan Am taking the lead. Two American companies, Boeing and Douglas were manufacturing jets. Both were sought by Juan Trippe, who acquired 20 Boeing 707s, and 25 DC-8s. On October 26th, 1958 the Boeing 707 carried passengers from New York to Paris, marking the beginning of the jet era for Pan Am.

The airline was in the perfect position to be marketed the way it was in the 1960s. Heroes in Hollywood movies would fly Pan Am and ads about the airline would feature the most adored actors. A culture was being developed around the Pan Am brand.

One Wrong Step

Pan Am’s adventures took a wrong turn in the mid-1960s. With most of his audacious ventures resulting in success for the airline, Juan Trippe decided to invest in supersonic transports (SST). SSTs are high-speed passenger planes that travel faster than the speed of sound. These planes were glorious on paper, the possibility of which was being explored by Britain and France.

However, there were many problems with SSTs, mainly that they were expensive to conduct research on, let alone build, and they were harmful to the earth’s environment. The American government under John F. Kennedy was skeptical of this project but had not yet decided. That did not stop Juan from contracting with France for an option to buy SSTs when they were developed. Meanwhile, Juan convinced Boeing to construct the 747s, which would fly along with Boeing 707s until the SSTs were ready to hit the skies.

Two things went wrong. First, Pan Am did not buy the SSTs. The fund for the American SST project, pushed by the Federal Aviation Authority Administrator, Najeeb E. Halaby, also closed. The SST never became a success in commercial aviation. Second, the 747s were largely bought because of Juan Trippe’s predictions that more people would travel by air in the 1970s. It was a wrong prediction. The Boeing 747s, for their gigantic size and marvelous design, had their seats half empty in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Air traffic was unpredictably less, and the new investments into 747s cost Pan Am billions of dollars.

Point of No Return?

Juan resigned as the CEO of Pan Am in 1968, just as the airline started losing money. He was succeeded by Harold Gray, followed by Najeeb E. Halaby in 1970. None of them could change the airline’s fate, as it incurred losses and burnt money. Other than the accumulation of Boeing 747s at the wrong time, a few more reasons contributed to Pan Am’s losses.

First, Pan Am was no longer the only airline flying transatlantic flights; that era was gone. At this point, the aviation industry had expanded as more and more airlines emerged. These airlines would be in different states of America, and the politicians of those states would lobby policies for them in Congress. Second, Pan Am was still not flying domestic flights due to CAB’s disapproval. William T. Seawell joined as CEO of the airline in 1971. He was notorious for his behavior as the CEO. He also laid off thousands of Pan Am employees due to financial difficulties.

After the Deregulation Act of 1978, which effectively took the CAB’s power to regulate airlines, Pan Am did not need the CAB’s approval to fly domestic routes anymore. William T. Seawell acquired the National Airlines in 1980, a Florida-based airline, with a considerable web of routes. The acquisition should have helped Pan Am, but that did not happen. The company kept losing money. Running out of cash rapidly, William sold the airline building to the Met Life Insurance company, which still owns it. The airline-owned Intercontinental Hotel chain was also sold to a British company, Grand Metropolitan in 1981.

Loss of a Legacy & the End of the Pan Am Era

The situation was so bad, that Edward Eker, who succeeded Willaim T. Seawell, started funding the airline with the salaries of its employees. The employee pension funds were also frozen, and pay freezes negotiated to fund the airline kept extending. This created a tense environment within the company, as pilots and other employees felt on edge and insecure about their future and the future of Pan American Airwats.

The labor unions went on strike against the pay freezes. This meant that the company’s culture and the trust between the management and employees were vanishing. The distrust heightened when, in 1985, Pan Am sold the Pacific routes and some of its planes to United Airlines. Pioneer of the Pacific routes, Pan Am had now lost its legacy.

Since then, Pan Am never recovered. In 1977, Pan Am Flight 1736 was one of the deadliest aviation disasters in history. The accident occurred when KLM Flight 4805 collided with the Pan Am Boeing 747 on the runway, killing all 248 people on board the KLM plane and 335 of the 396 people on board the Pan Am plane. As security concerns mounted, this was one of the several disasters that deterred people from flying.

In 1988, the Lockerbie crash caused by a bomb in a suitcase on Pan Am flight 103, killing more than 200 people around Christmas time, translated into empty airplanes for most of 1889.

In 1990, the situation worsened with the recession. The airline lost $394.1 million in the final quarter of 1990, after the beginning of the recession in July, and $249.2 million in the first three months of 1991. The Persian Gulf War also contributed to these losses because air traffic had reduced significantly as a result of the war.

Several efforts were made at different points. On January 8, 1991, with the help of the Bush government, Pan Am struck a deal with the Bankers Trust of New York and United Airlines, whereby the airline would give its Heathrow operations to United Airlines in exchange for 150 million dollars from both parties, subject to Pan Am’s filing of Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Subsequently, Delta Airlines acquired Pan Am’s routes and pumped money into Pan Am while restructuring it. As fate would have it, none of these efforts made any difference.

The airline was bound to be shut down. In December 1991, after Delta’s efforts to revamp Pan Am, it pulled off its funding. Pan Am was dead. By December 4, 1991, all of the Pan Am employees were on American soil. They were bent up in recession and no longer employed. The Pan Am era had wound up painfully. The brainchild of Juan Trippe, who died in 1981, was a memory of the past.

Conclusion

There is something melancholic about glory turning into dust. Pan American Airways was synonymous with grandeur, luxury, and new-found experience in the early and mid-1900s. It was a poster product of American soil, but that which was an inevitable failure, thanks to some of the decisions of its CEOs, and the nature of global events that impacted its success. Notwithstanding, the aviation industry is not an easy industry to survive in, but that which gives birth to various empires, many of which were short-lived.

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please check the Submissions page.

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.

Noorulain Shaikh graduated with an LLB (Hons.) degree from the University of London. She is keen on geographical, sociopolitical, and legal aspects of world affairs. She is a published author of articles concerning international law and regional policy affairs.