The author is studying Economics at the National University of Science and Technology (NUST) with a keen interest in financial affairs, international relations, and geo-politics.

On New Haven’s High Street stands an eerie, imposing brownstone building with a distinct Gothic flourish. It’s known more simply as “the Tomb,” a structure that has housed Yale University’s secret society “Skull and Bones” since 1856. Since its inception, the secretive society has captivated imaginations, fueled conspiracy theories, and shaped the trajectories of American elites, from presidents to CIA directors.

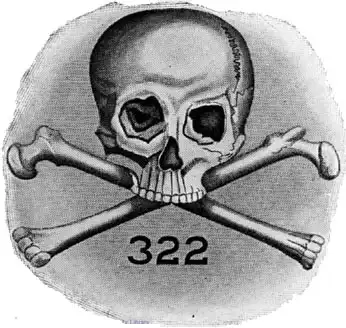

1832 William Huntington Russell and Alphonso Taft (father of future President William Howard Taft) founded the society following a dispute among Yale’s debating societies over Phi Beta Kappa awards. Inspired partly by German Burschenschaften (student societies), the founders sought to create a brotherhood that blended intellectual rigor with clandestine rituals. The society’s original name, the Eulogian Club, alluded to Eulogia, a fictional goddess of eloquence. Still, it soon adopted the darker moniker “Skull and Bones,” with the cryptic number 322 etched into its insignia.

The number’s meaning remains a mystery; some tie it to Demosthenes’ death in 322 BCE, symbolising the fall of Athenian democracy, while others believe it references a German precursor society. Whatever its origin, “322” became a lodestar for Bonesmen, who allegedly date events from this year in internal documents.

Each spring, Yale’s rising seniors endure ‘Tap Day,’ a tradition as tense as theatrical. Since 1879, Bonesmen have roamed campus, clapping chosen juniors on the shoulder and uttering, ‘Go to your room,’ a command signaling membership. Only 15 are selected annually, a practice unchanged since the society’s founding. The criteria were highly selective, focusing on all-rounders who could provide academic excellence, leadership, and, historically, lineage. Prescott Bush (George H.W. Bush’s father), Bush Presidents, John Kerry, and media moguls like Henry Luce bore the prestigious Bones pin.

Yet the exclusivity and secrecy bred controversy. Until 1992, women were barred from entry, a policy only overturned after a bitter alumni feud. In 1991, with the inclusion of seven women in the ranks, the traditionalists protested and changed the Tomb’s locks, forcing initiates to meet elsewhere. The traditionalists would lose it democratically with 368–320 in favor of coeducation. However, lawsuits and public sparring between figures like William F. Buckley and John Kerry laid bare the society’s generational rift.

Behind the Tomb’s iron doors, eerie rituals unfold in the shadows. Initiates reportedly lie in coffins, confessing intimate secrets, while older members don robes and adopt pseudonyms like “Long Devil” or “Magog”. The society’s obsession with mortality is literal: Legends claim it houses stolen relics, including the skulls of Apache leader Geronimo, President Martin Van Buren, and Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa.

The Geronimo tale, though disputed, persists. In 1918, Prescott Bush allegedly exhumed the warrior’s remains during a Yale University expedition, a claim Geronimo’s descendants unsuccessfully challenged in court in 2009. Whether fact or folklore, such stories cement the society’s macabre foundations and rituals that still persist. The society’s actual influence lies in its alumni network. Members gain lifelong access to a cabal of power brokers, epitomised by Deer Island, a 40-acre retreat on the St. Lawrence River. Once a lavish estate with tennis courts and catboats, today it’s a dilapidated “dump” where Bonesmen “rekindle old friendships” away from public scrutiny.

Critics argue this camaraderie translates to unparalleled influence. Three U.S. presidents, Supreme Court justices, and CIA directors, including George H.W. Bush, have been Bonesmen. During the 2004 election, both George W. Bush and John Kerry, facing questions about their membership, deflected with identical quips: “It’s a secret.” Such opacity fuels theories of a “Deep State” nexus, though skeptics note that correlation does not equal causation.

In recent decades, Skull and Bones has grappled with its identity. Once a pipeline for Cold War elites like Henry Stimson (architect of the atomic bomb), it now faces accusations of irrelevance. Younger members, steeped in progressive activism, clash with alumni over values like hierarchy and tradition. The Class of 2021 admitted no conservatives, mirroring a cultural shift toward a more liberal society that values inclusion and equality over secrecy and exclusionary influence.

Yet, the allure persists. Alexandra Robbins, the famous author of The Secret of Tombs, notes that Bonesmen still dominate Wall Street and Washington, albeit less visibly. “The network isn’t about ruling the world,” she argues. It’s about knowing the right people to call at 2 a.m.” Essentially, Bonesmen are an exclusive group within an already exclusive group of Ivy League students, creating an extremely powerful networking circle.

The secret society Skull and Bones thrives on paradox. It is a relic of Gilded Age elitism that adapts to survive, a brotherhood accused of occultism yet steeped in banality. Its rituals, equal parts absurd and arcane, mask a pragmatic truth: in a fractured world, the promise of belonging still holds power.

As the Tomb’s gates close on another initiation, one question lingers: Do Skulls and Bones shape history or merely reflect it? Like society itself, the answer remains shrouded, a riddle wrapped in a skull and guarded by bones.

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please check the Submissions page.

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.