The world is witnessing the rapid development of generative AIs. Contrary to the stark reality, this development is being framed as a solution to all contemporary global issues. However, the increasing environmental degradation resulting from AI development is being dismissed by big tech companies. The development of generative AI is characterized by the consumption of large quantities of electricity and water, i.e., training a single large language model (LLM) emits approximately 300,000 kg of carbon dioxide, equivalent to 125 round-trip flights between Beijing and New York. Even though the world is transitioning to sustainable energy development and discouraging the utilization of fossil fuels and oil in energy production. Yet, the development of AI in a vacuum with no regulatory mechanism poses a grave concern to environmental protection around the globe.

Notwithstanding, this development is being dominated by the global North, whereas the global South is bearing the shadow environmental cost. Despite the presence of procedural obligations under international law for the protection of the environment and the prevention of cross-boundary harm. No such practices have been adopted by the AI development companies, policymakers, or think tanks. This article argues for the urgency of adopting Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), a procedural obligation under international law, as a necessary mechanism of anticipatory governance and minimizing the shadow environmental cost in the global south.

Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) in International Environmental Law

Environmental impact assessment first emerged as a procedural obligation under international law in 1972 after the Stockholm Convention, and now it has been developed into an international and domestic mechanism for the integration of environmental considerations into socio-economic development and decision-making process. An environmental impact assessment describes a process that produces a report of the foreseeable environmental impact of the proposed activity or the project. Secondly, it provides policy or decision makers with all the necessary information on environmental consequences and proposed alternatives to prevent cross-boundary harms. Thirdly, it provides a mechanism for ensuring the participation of potentially affected states or individuals in the decision-making process. It has been formally recognized as a binding obligation in Principle 17 of the Rio Declaration, providing, “Environmental impact assessment, as a national instrument, shall be undertaken for proposed activities that are likely to have a significant adverse impact on the environment and are subject to a decision of a competent national authority.” Furthermore, Principle 21 of the Rio Declaration imposes a binding duty on the states for cooperation for environmental protection and sustainable development. Moreover, the ICJ in the pulp mills case, “Argentina Vs Uruguay,” formally recognized EIA as a binding procedural obligation under general international law.

Despite decades of international environmental law designed to assess and mitigate large-scale environmental harm, AI development operates in a near-total regulatory vacuum. However, it is pertinent to govern the development of AI to mitigate the anticipated environmental impacts.

Generative AI Development as Environmentally Significant Activities

Generative AI development involves creating models like LLM, GAN that learn patterns from an extensive collection of data to generate novel content such as images, audio, and videos using techniques like transformers operating through large data sets. Moreover, the rise of generative AI has increased electricity demands, evident from the escalating demand for data centers.

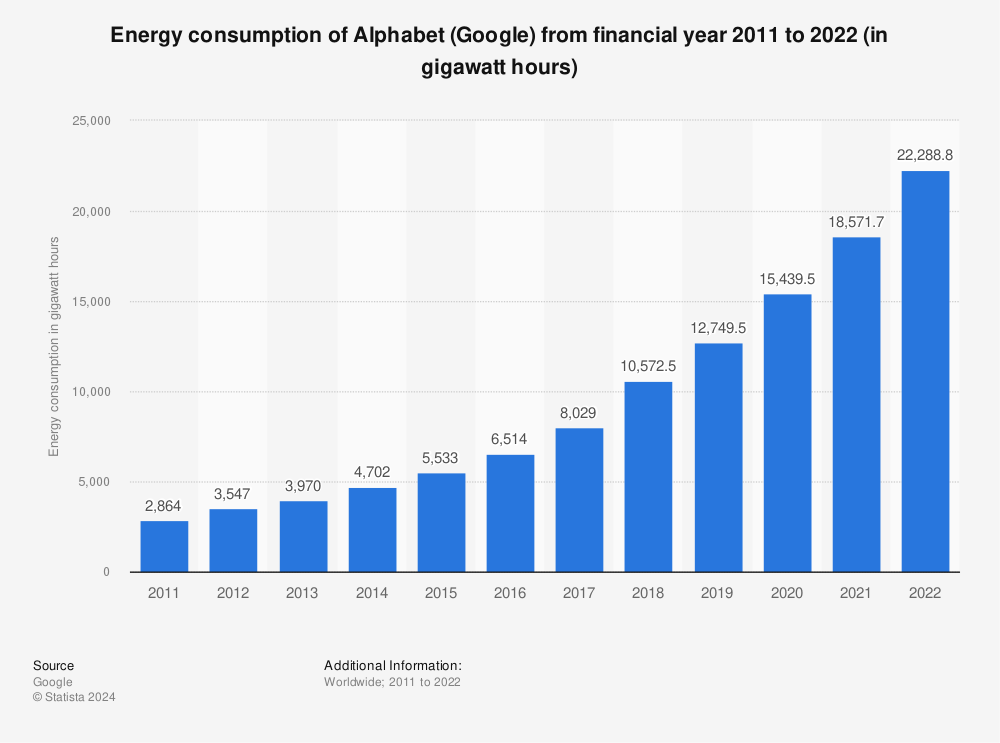

Data centers serve as the backbone of an AI-driven world, providing the critical infrastructure necessary to meet the increasing demands for computational power and data storage. Consequently, since 2012, the number of data centers has surged from 500,000 to 8 million around the world. These data centers, to run their operations, require large quantities of energy and water. Estimates project that the global requirement for water for the development of AI will increase up to 4.2-6.6 billion cubic meters in 2027. In furtherance of that, large quantities of e-waste have been produced in these data centers. However, the disposal of the exact volume of e-waste containing toxic and hazardous materials has still been unclear, which poses a significant threat to human health and the environment.

Find more statistics at Statista

Apart from that, the development of AI and the establishment of data centers require large quantities of minerals and metals, including cobalt, aluminum, and rare earth metals, including gold and silver. These metals and minerals undergo an extensive process of extraction and purification to achieve the level of purity required for building the AI. The largest AI data center is the Citadel Campus, Reno, Nevada, USA, built by a US-based company that spans 7.2 million square feet to illustrate the large volume of minerals required for the sustenance of these critical structures.

Moreover, these minerals have been extracted from resource-rich countries in the global south. The supply of these minerals has been controlled not by market dynamics but shaped deeply by geopolitical factors. Currently, China controls the market of critical minerals used in the infrastructure of AI, such as antimony, gallium, germanium, and rare earth element, on the contrary, the United States is the leading producer of the AI-related products on the manufacturing stage – this process heavily depends on the high-level skills in such fields as intellectual property, product design, automation and fabrication.

Meanwhile, no access and benefit sharing mechanism has been adopted under any international instrument for the provider states to prevent the expropriation of their natural resources.

Data Center Energy Consumption Surges Amid AI Boom by Anna Fleck, licensed under CC BY-ND

Furthermore, AI models consume more energy than traditional technological applications such as Google Search, email, data retrieval, communication, or content generation. For example, a single search on OpenAI ChatGPT consumes ten times more energy than a simple Google search. As a result, a leading authority, the International Energy Agency (IEA, 2024), provides that data centers, cryptocurrencies, and artificial intelligence took about 2% of the total consumption in the year 2022, at 460 TWh of electricity of world power consumption. According to the same report, this number is expected to double in 2026, reaching between 620 and 1,050 TWh.

This increasing demand for energy is surpassing the available supply in multiple regions of the world. It is pertinent to mention that the exponential increase in the development of AI, the creation of data centers, the number of users, and the demand for energy is alarming. It is causing irreversible harm to the environment. Therefore, there is a serious need to adopt Environmental Impact Assessment to evaluate and minimize the adverse environmental impacts of AI development and adoption of an extensive access and benefit sharing (ABS regime) to prevent the expropriation of natural resources of the global south.

The Regulatory Gap: Why The Existing Regulatory Mechanism Falls Short

The development of AI took place in the absence of any regulatory mechanism. The tech companies have developed AI without taking into account its environmental cost and its impact on the underprivileged segments of the world. The only regulatory principles regarding AI development are the EU AI Act, 2024, and the OECD AI principles.

However, the focus of the EU AI Act is merely on fundamental rights, protecting the individual rights of privacy and dignity. It is completely silent on environmental protection and sustainable development. Similarly, the OECD AI principles call for the protection of the environment and sustainability. Nonetheless, the principles are non-binding and provide no implementation mechanism for the prevention of foreseeable environmental harm. The protection of the environment is treated as peripheral or left completely unacknowledged in the development of generative AI.

Although the protection of the environment is the utmost responsibility of the world, it requires global cooperation. Yet, the development of AI without taking into account its environmental cost poses a significant threat to the well-being of future generations. Moreover, the principle of intergenerational equity in international law imposes a duty the protect the environment for future generations.

In spite of the robust international principles based on sustainability, equity, and protection, the unregulated AI development is disconcerting. AI development is not merely a digital activity but an environmental activity as well. Therefore, there is a serious need for the adoption of environmental impact assessment (EIA) for AI activities. The EIA regarding AI activities must disclose the consumption of energy sources, water usage, lifecycle impacts, and possible disposal of e-waste generated during the activities.

The project planning must include iterative assessments for environmental protection, including initial assessments before deployment, as well as continuous updates as the project scales up. Furthermore, it should ensure the participation of affected communities in the AI activities in the decision-making process, especially representation from the global south.

The adoption of EIA is necessary to manage risks and regulate AI activities, so they should not operate in a vacuum.

Conclusion

Artificial intelligence is typically regulated as though the effects are intangible, limited to data flows, algorithms, and abstract dangers to rights and values. However, the environmental impact of AI systems is not a side effect or a hypothetical one. It is predictable, accruing, and expanding globally. The lack of formalized ways to evaluate these effects is not an indication of the lack of legal instruments but rather of the inability to impose the wisdom of governance in a new technological sector.

Environmental Impact Assessments have long been a tool of international environmental law to protect against exactly the aforementioned blind spots, those whose potential effects remain unknown, whose damages can be cross-border, and about which regulation requires prospective action rather than the retrospective response. The fact that EIAs would be adapted to large-scale AI systems would not limit innovation; instead, it would train the innovation to incorporate transparency, accountability, and informed decision-making into the development of AI at its early stages. With the constant development of global AI governance frameworks, their legitimacy will be judged by how they address the material aspects of the spread of AI, as opposed to their consideration of environmental harm as a background issue. Making environmental impact assessment part of the governance of AI is a feasible and legally sound measure towards anticipatory regulation, the type of regulation that realizes that technological advancement, as well as environmental protection, cannot be effectively governed in a vacuum.

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please visit the Submissions page.

To stay updated with the latest jobs, CSS news, internships, scholarships, and current affairs articles, join our Community Forum!

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.