Introduction

Born in 1332, a Tunisian historian, sociologist, and historiographer, Ibn Khaldun is considered one of the greatest minds the Muslim world has produced. His primary work, titled Muqaddimah, has been regarded as one of the greatest works in which he explained the nature of history in a systematic manner.

Ibn Khaldun can be credited for providing us with key concepts and theories such as those pertaining to historical causation, the rise and fall of the political order, and elite socialization. He has also provided a comprehensive framework that is key to understanding the imperial political economy. One of the key concepts propounded by Ibn Khaldun in this regard is asabiyyah. The concept of asabiyyah is a significant one, as it helps us to explicate the key phenomena in our contemporary world.

The Concept of Asabiyyah

The word “asabiyyah” can be described in a number of ways as various meanings have been ascribed to the word such as solidarity, group feeling, common will, or national feeling. But in a broader sense, it can be defined as a cohesive force that keeps the people intact. The phenomenon of Asabiyyah is premised upon two things, namely kinship and ideology.

The factor of kinship is predominated in nomadic or semi-nomadic social setups where the population is relatively lower and people know one another through a personal acquaintance. Kinship in such a sort of setup played a crucial role in social cohesion. The other type of Asabiyyah is grounded in an ideology that is prevalent in a sedentary lifestyle where the population is large enough to hinder personal acquaintance.

The said ideology, which could be a religion or any other type of ideology, plays a cohesive role in this regard and keeps the people united. It is in this later spirit that we will explore how the phenomenon of asabiyyah can be employed to explain the communal nationalisms of both Muslims and Hindus, with a particular emphasis on the subcontinent in the subsequent paragraphs.

Asabiyyah and Nationalism

The modern notions of nationalism and asabiyyah enjoy an intimate relationship, as both concepts exhibit similarities. Masood Ashraf Raja, an associate professor of post-colonial literature at the University of North Texas, has termed asabiyyah as one of the early definitions of nationalism. As mentioned earlier, the word asabiyyah can be translated as a cohesive force, solidarity, group feeling, or sentiment that ties the people together.

In the same manner, the renowned historian K.K. Aziz has defined nationalism as “a sentiment, a consciousness, a sympathy which binds a group of people together. It is the desire of a group of individuals, who are already united by certain ties, to live together, and if necessary to die together.” Moreover, the ideology that keeps the people together in a sedentary lifestyle in Ibn Khaldun’s asabiyyah is religion. In the same manner, religion also plays a crucial role in arousing nationalistic sentiments, or nationalism per se. For instance, Jewish Zionism, Burmese Buddhism, and Japanese Shintoism are a few examples that illustrate this fact. Given the similarities that exist between the two notions, the concept of asabiyyah can be employed to explain the communal nationalism of both Muslims and Hindus in the subcontinent.

Muslim Nationalism

The roots of Muslim nationalism in the subcontinent can be traced back to the 1857 uprising. The uprising proved to be a lost endeavor and was suppressed brutally by the British East India Company. The Muslims, in particular, were held responsible for the uprising and bore the brunt of Britain’s repression. The result was the suppression and isolation of the Muslims.

Out of this suppression and isolation, there emerged a need for solidarity among the Muslims. K.K. Aziz has aptly illustrated this point; according to him, “This was the first casting of the seeds of nationalism, the first awakening to the need of solidarity.” In due course, Muslim nationalism evolved significantly and ultimately culminated in the creation of the nation-state of Pakistan.

The core of Muslim nationalism was essentially premised on religion. To draw an analogy, the Muslims of Bengal were as different from the Muslims of Punjab in terms of ethnicity as the French people are from the Germans; however, it was religion that played a gluing role among the Muslim polity of the subcontinent. By the turn of the twentieth century, according to Christophe Jaffrelot, Islam became an exclusive dividing line between Muslims and Hindus. Echoing the view of Jaffrelot, Francis Robinson also asserts that Muslims and Hindus have never overcome their cultural differences and that Muslim nationalism was, to a great extent, premised upon these old-age differences.

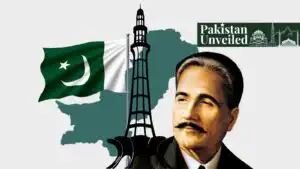

The pioneers of Muslim nationalism, such as Allama Muhammad Iqbal and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, had time and again reiterated Islam as the core of Muslim nationalism, as evident from their speeches and addresses. And how can one forget the blunt use of religion in the 1946 elections by the Muslim League in Punjab, which ultimately paid dividends in the result? In his fortnightly report, the then Punjab governor, Bertrand Glancy, reported to viceroy:

“The Muslim League orators are becoming increasingly fanatical in their speeches. Maulvis and pirs and students travel all around the province and preach that those who fail to vote for the League candidates will cease to be Muslims; their marriages will be no longer valid and they will be entirely excommunicated.”

Hindu Nationalism

Hindutva, or Hindu nationalism, has remained a part of Indian politics. For quite some time, it has now occupied a central stage on the horizon of Indian politics under the BJP’s rule—well known for its extremist Hindu nationalism. The rise of Hindu consciousness can be traced back to the 17th century in the empire of Shivaji; however, the genesis of modern political Hindu awakening can be found in the early 19th century.

Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Dawarkanath Tagore, the founders of the Brahmo-Samaj movement, are considered pioneers of early modern Hindu nationalism, which was progressive in its outlook. However, in due course of time, the concerned progressive political awakening morphed into a form of Hindu nationalism that was entirely communal at its core. In the early 20th century, the Hindu Mahasabha and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), collectively termed “Sangh Parivar” became the flag bearers of communal Hindu nationalism. Madan Mohan Malaviya, Damodar Savarkar, K. B. Hedgewar, M.S. Golwalkar, and Lala Lajpat Rai became its pioneers.

Hindu nationalism invokes “Hinduism” as a culture and religion to unite the Hindus and urge them to strive to make India a Hindu Rashtra predicated upon the Hindu ethos and religion. It tends to identify the nation through a narrow lens of identity—the Hindu identity. For instance, according to Savarkar, one of the chief proponents of Hindu nationalism, “an Indian is anyone who regards India as both the fatherland and holy land.” It implies the exclusion of Muslims and Christians who do not regard India as a holy land. He further added, ‘‘India cannot be dissociated from Hindu people and Hindu culture.”

Conclusion

As evident from the above discussion, the communal nationalisms of both the Hindus and Muslims in the subcontinent were characterized by a cohesive force that happened to be a religion. It is the same cohesive force to which Ibn Khaldun had alluded in his notion of asabiyyah in the 14th century. In Ibn Khaldun’s view, asabiyyah played a significant role in the emergence of civilization. In the same manner, the communal nationalism of Muslims with the interplay of other factors, played a crucial role in the formation of Pakistan. In the case of Hindu nationalism, it is striving for a Hindu Rashtra. Thus, by employing the notion of asabiyyah, one can get a detailed insight into the communal nationalisms in South Asia.

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please check the Submissions page.

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.

Syeda Seerat is an MPhil scholar at Quaid-I-Azam University and a research associate with the South Asia Times.