Pakistan is said to be a nation that is perched on a demographic dividend. Its population is not only younger than 30 years of age, but almost two-thirds, which, on paper, should be an advantage for growth, innovations, and increased prosperity. Nevertheless, demographics is not fate. A youth bulge is easily transformed into a burden on the populace, particularly without jobs, skills, and productivity. The red flags are already present in the case of Pakistan.

As the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics says, over two-thirds of the Pakistan population is below the age of 30, and approximately two and a half to two million youths join the working-age group annually. However, the economy is generating relatively lower formal productive employment. The outcome is a further discrepancy between aims and chance, one that threatens to cut major development, stability, and societal integrity.

A Youth Bulge Without Jobs

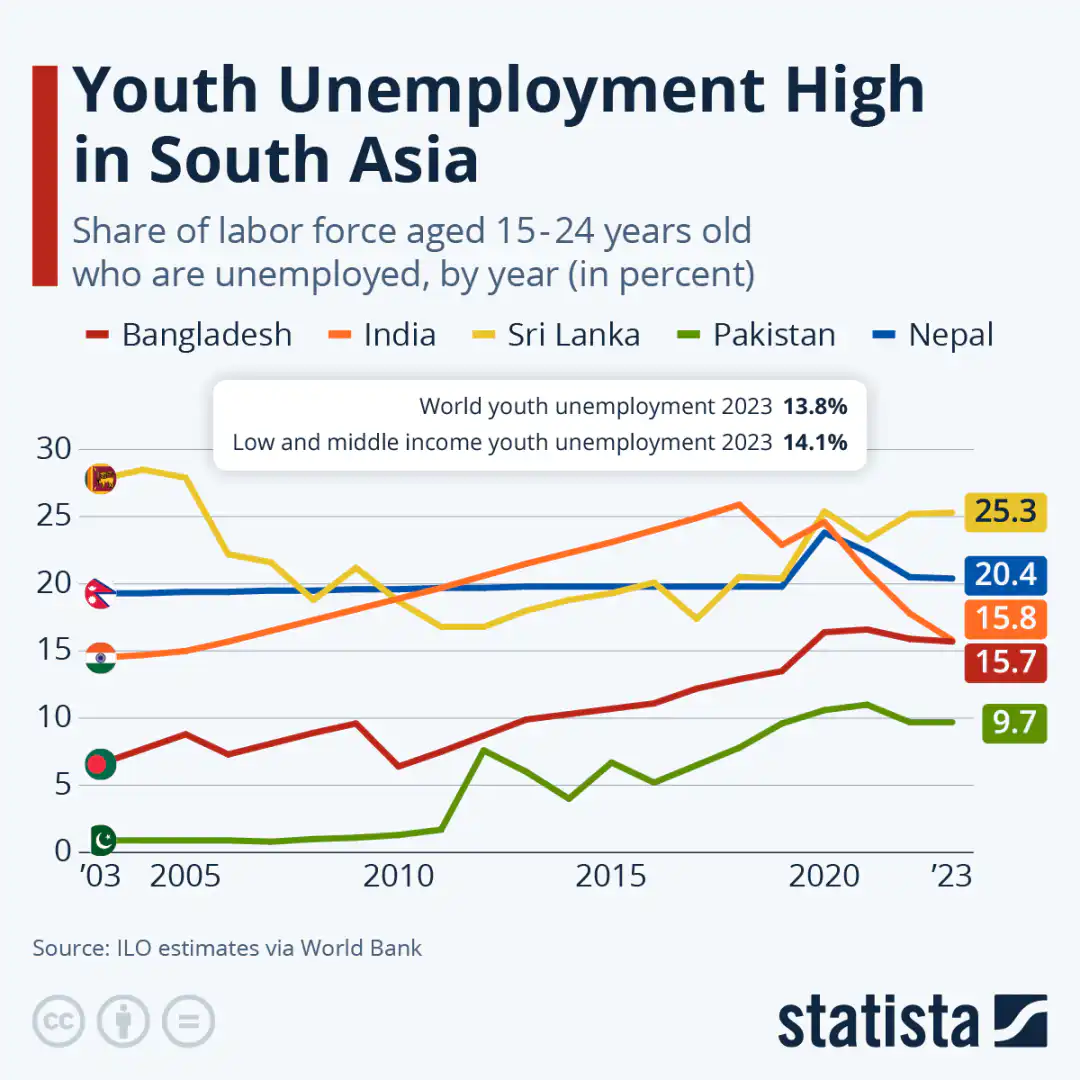

The rate of participation of the labor force in Pakistan is also low when compared with the rest of the region, particularly among youth and women. Formal statistics indicate that youth (15-24) unemployment stands at approximately 11-12%, although headline figures are deceptive because of underemployment and informality. According to PBS labor force surveys, more than 70 percent of the employed youths are working in informal or low-productivity industries.

This implies that there are millions of young Pakistani citizens who are technically employed but economically idle—they earn too little, learn too little, and contribute too little to the development of the economy in the long run. Pakistan has one of the lowest estimates of employment elasticity of growth by the World Bank, which means that GDP growth does not translate into job creation.

This macroeconomic impact is dire. An increase in labor supply exceeding the increase in productive employment will result in stagnant wages, lower household savings, and low domestic demand. In the long run, this destroys the principles of growth.

Degrees That Are Not Employable

Education has grown fast, whereas skills have not. Pakistan is currently breeding hundreds of thousands of graduates annually, but employers constantly claim that they cannot find job-ready workers. According to the World Bank enterprise surveys, more than 60 percent of the companies consider the lack of skills as a significant barrier to business growth.

Educational structure is one of the major offenders. Pakistan spends approximately 2 percent of its GDP on education, which is lower than the suggested international standard of 4-6 percent. Worse still, the distribution of that expenditure: rote learning is prevalent, vocational education is poor, and academia-industry connections are insignificant.

The outcome is a typical skills mismatch. The youth get qualifications that are not translated to productivity, and companies produce less than they can because of human-capital limitations. As the Asian Productivity Organization lists, labor productivity in Pakistan is one of the lowest in Asia, much lower than countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam.

The Productivity Trap

Poor skills translate into poor production—poor production keeps the level of wages down. This is the reason Pakistan is in the trap of low-value production and commodity exports. An average Pakistani worker is half as productive as the workers in East and Southeast Asia. According to the World Bank productivity indicators, the output per worker in Vietnam is approximately 2.5-3 times that of Pakistan, although the two countries have had a similar income level for 20 years.

This productivity gap is why Pakistan is not able to increase exports, climb up the value chains, or find sustained foreign investments. It also describes the lack of youth unemployment even when economic growth is going on: companies become cannily careful, slow to automate, slow to scale, and shy to grow.

The Illusion of Entrepreneurship

With the challenge of creating fewer job opportunities, the solution is more and more entrepreneurial efforts from policymakers. However, this is a fallacy of a story. Start-ups cannot absorb millions of young entrants annually—particularly those who come into the world in an economy that is marked by informality, lack of finance, bad infrastructure, and regulatory sclerosis.

According to World Bank financial inclusion statistics, less than 5 percent of young people in Pakistan are able to access formal credit. Venture capital is still minute when compared to the population, and the majority of the so-called entrepreneurs are running survival businesses and not scalable enterprises. Entrepreneurship is a slogan, not a solution, unless well-built ecosystems, skills, capital, regulation, markets, etc., exist.

When a Youth Bulge Makes It Risky

Idleness among the youth does not only imply lost production. The continued youth exclusion promotes brain drain, informality, and social instability. Over 860,000 Pakistanis were abroad seeking jobs in 2023 alone, with many of them being young and semi-skilled. This exodus is not only an opportunity in a foreign land but also an irritation back home.

The International Monetary Fund has severely cautioned that states with youthful populations and low rates of labor are at risk of political instability and reduced long-term economic development. The demographic burden may turn into fiscal and social instability for Pakistan, where fiscal space is already limited.

Turning the Time Bomb into a Dividend

Pakistan has a limited opportunity to intervene. The young generation that poses as a threat to making the world unstable can turn into a growth engine should the policy priorities change strongly.

Five reforms matter most:

- Job-rich Development: Put emphasis on export-oriented manufacturing, IT-based services, and construction (sectors with high employment multipliers).

- Education Reform—Skills First: Match the curriculum to market demand and scale up vocational and technical training.

- Hiring by the Private Sector: Minimize regulatory friction and informality that can deter formally hired firms.

- School-to-work Pipelines: Increase apprenticeships, internships, and employer-based training programs.

- Specific Entrepreneurship Assistance: Not generalized rhetoric of start-ups, scale-ups, and high-potential businesses.

The Clock Is Ticking

Demographics purchase time—but not plenty. The youth bulge in Pakistan is not going to be eternal. When millions of youths continue to be under-skilled and under-employed, the payoff will reverse to slow down growth, state budgets, and societal unity. The future of Pakistan will not be decided by the number of young people it has. It will depend on the productivity of such youths that they will be permitted to attain.

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please visit the Submissions page.

To stay updated with the latest jobs, CSS news, internships, scholarships, and current affairs articles, join our Community Forum!

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.

Dr. Ghulam Mohey-ud-din is an urban economist from Pakistan, currently based in the Middle East. He holds a PhD in economics and writes on urban economic development, macroeconomic policy, and strategic planning.