Arts, literature, and drama have styled the changes and transformations in culture in Pakistan throughout its history. Particularly, the 20th century is described as an age in which cultural icons crossed popular societal norms, challenged those in positions of authority, and projected the politics of change. Figures like Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Bano Qudsia, Sadequain, and Zehra Nigah are far more than some artist-intellectuals; they are spearheads of progressive ideals. Through their works, be it in poetry, literature, or visual art, they have built narratives that push boundaries for equality, freedom, and justice in amounts that bear such relevance even today.

In juxtaposition to the vibrant past, it is shocking how the cultural landscape has suffered evolution (or rather, regression). This has put Pakistan at a crossroads where traditionalism and conservatism stand in the present, in contrast to the free flow of expectations in the past. The vibrant world of Pakistani art, dramas, and poetry, which raised issues and vindicated progressive values, appears to have taken the road back toward the myths that often extol patriarchy, orthodoxy, and conformity today.

This article discusses how icons in art throughout history argued for progressive ideals, what roles they played in shaping society, and how radicalism reflects the way Pakistan evolved along the cultural and nationalistic trajectory.

The Progressive Artists of Pakistan

During the early years after independence, creativity and artistic freedom were the buckles of Pakistan. Those years saw some of the most innovative artists, writers, and poets form a cultural renaissance in Pakistan. They were not just artists, they were social activists who made sure that every voice was raised against oppression.

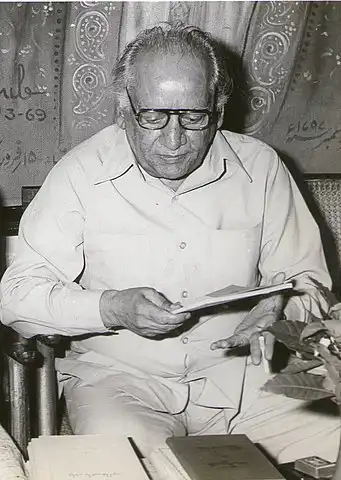

Faiz Ahmed Faiz, the most renowned poet of Pakistan, was also a political firebrand. His poems became a symbol of rebellion rooted in the values of justice against oppression. His famous poem Hum Dekhenge, written during the Zia regime, became a chant against institutional despotism. His poetry with themes of revolution, equality, and the desire to be free occupies a major section of Pakistan’s literary history.

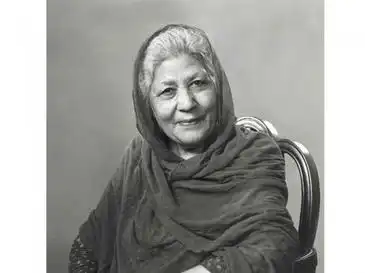

Bano Qudsia, one of the finest writers and playwrights in Pakistan, rendered a unique and progressive approach to storytelling. Her plays and novels explored some serious social issues of gender inequalities, class struggles, and women’s conditions in a conservative society. From the stage of her famous drama Aadhi Baat, Bano Qudsia tackled taboo subjects with a gentle maturity that broke the barriers of silence surrounding emotional and social taboos. Though women’s voices ceased to become loud, her delicate scrutiny of relationships, personal freedoms, and collective expectations was revolutionary.

Sadequain was among the top painters and calligraphers of Pakistan who interrogated the place of religion and politics in the identity of Pakistan. He became known for his bold approach to calligraphy, combining traditional Islamic art with a modern flair. His works questioned conventions in society, particularly concerning religion and culture. His murals in Karachi and Lahore introduced new styles and forums for art to be exhibited in public spaces, bearing the weight of intensely personal and deeply political meaning. Sadequain’s art is a cultural commentary and an assertion of individual agency in the face of conformity.

Zehra Nigah is one of the more prominent voices in contemporary Pakistani poetry, portrayed through a feminist lens. She uses poetry as a way to shed light on women’s quotidian experiences, delineating through subtleties and nuances their emotional struggles. Zehra Nigah’s writing was groundbreaking; it confronted the silent wars women have fought within a society that often forced them into secondary jobs. Her work is a mirror of the times and a call for social change.

These artists represented a more progressive phase in the Pakistani history of art, an age in which art, literature, and public discourse collaboratively questioned and often challenged the authorities. They went beyond conservative thought, using their media to advocate gender equality, social reforms, and political freedom.

The Role of Dramas and Popular Culture in Shaping Progressive Narratives

Besides poets and artists, the world of Pakistani dramas in the 80s and 90s also had space for progressive thought. Early Pakistani dramas were very bold, they used to tackle complex social issues like corruption, class divide, and female repression. Shows like Aangan Terha and Tanhaiyan were the epitome of progressive thought of that time. These dramas promoted tolerance, self-empowerment, and intellectualism.

Aangan Terha was a satire that cleverly mocked societal and political norms. The characters though caricatures represented the contradictions in the country’s political and social structure, it was a bold commentary on Pakistan’s political reality. Tanhaiyan touched on the emotional and social complexities of women’s lives, subtly challenging the traditional roles imposed on them. These shows had strong independent women, so they paved the way for the discussion of women’s rights and social change in Pakistan.

Today, however, the tone of Pakistani dramas has changed completely. While there are still some progressive voices in the industry, most of the content that’s aired today is centred around patriarchal family structures, romantic melodramas, and idealized conservative values. Female characters are often shown as passive, subservient, or as victims of circumstances, with no room for individuality or autonomy. The shift towards a conservative narrative especially in mainstream media has pulled back the space that progressive dialogue had in art and culture.

The Role of Conservatism in Today’s Cultural Landscape

Conservatism in Pakistan’s culture started to rise in the 1980s when General Zia’s regime made Islam a part of state policy. Zia used religion as a unifying force and a tool of control, to counter the progressive movements that flourished in the previous decades. The military’s influence on art, literature, and media through censorship, moral policing, and state-driven narratives, choked the space for critical discourse and dissent. Writers and artists started to face pressure to conform to nationalistic, religious, and patriarchal norms, making it increasingly difficult to produce work that questioned authority or highlighted social issues like gender equality, human rights, or political freedom.

As Pakistan’s cultural and political landscape evolved, narratives in the arts began to reflect this more on the conservative side. The earlier richness of ideas in literature, the arts, and cinema has now been replaced with stories that extol conformity of thought, family values, and religious orthodoxy. In literature, social issues like women’s oppression or class struggle started to fade away. Instead, media and drama serials started promoting idealized family life and morality, often centred around traditional gender roles and religious values. These changes reflected the growing influence of religious leaders and conservatives in shaping public opinion and pushing a more restrictive and polarized view of society.

Zia-ul-Haq’s censorship had long-term effects on artists and intellectuals. As societal taboos grew stronger, topics like women’s autonomy, sexual rights, and criticism of political figures became harder to tackle. Writers who dared to write on these subjects risked exile, imprisonment, or censorship. This created an environment where most public art was sanitized to avoid controversy or punishment and art became a tool for social and political commentary less and less.

In today’s Pakistan, these conservative values are still prevalent. The media which used to be the platform for subversive and progressive ideas now promotes narratives that fit into traditional family structures and Islamic values. Issues like gender equality, youth rebellion, or political corruption hardly get the attention they used to. Instead, family-oriented dramas heavily laced with conservative ideologies dominate the prime-time television slots. The focus has shifted to portraying “ideal” women as the pillars of family life, hardly ever delving into their individual struggles or social mobility. Political commentary which used to be rich with corruption, freedom, and identity now toes the line of nationalistic pride and sidelines the critical edge that made it so powerful in the past.

Religious conservatism also decides how art and literature are received by the public. Whatever challenges religious norms or questions the role of faith in politics is looked upon with hostility. Fear of being labeled un-Islamic has scared many artists and intellectuals from tackling these topics and has created a bubble of self-censorship where artistic expression is limited by the boundaries of societal expectations.

A Comparative Reflection: The Past and Present

The shift from progressivism to conservatism in Pakistan is a reflection of a change in values and priorities. In the past, Pakistan had a vibrant cultural scene where intellectual freedom, political dissent, and artistic experimentation flourished. Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Bano Qudsia, and Sadequain were the face of questioning authority and envisioning a more just and equal society.

The political landscape especially after the 1980s with military rule and the rise of religious conservatism has made cultural freedom less available and created an environment where tradition and conformity are preferred over artistic rebellion and intellectual critique. Art and literature today are more in line with the mainstream and topics that once challenged the social order are now pushed aside instead, we have narratives that promote national pride, family values, and religious dogma.

This raises important questions: What happened to the radical potential of art? How did Pakistan’s intellectuals, writers, and artists move from defying authority to being more cautious in their work? The progressive voices that once pushed the boundaries seem to have disappeared and in their place is a climate of censorship and political correctness.

But the audience has changed too. As Pakistan has become more polarized, with the lines between religiosity and secularism getting more defined, the audience’s expectations from art and literature have changed too. They want entertainment that fits into traditional values not thought-provoking, challenging work that can stir controversy. The space for radical ideas in the cultural landscape has shrunk and many artists are too scared to create anything that can challenge narratives.

Cultural Renaissance 2.0: A Blueprint for the Future

As Pakistan tries to figure out its cultural identity in a changing world, the idea of a “Cultural Renaissance 2.0” is necessary. This movement will build upon the progressive work of the past and add the tools and ideas of the digital and globalized age. It envisions a society where art, literature, and public discourse become the catalyst for critical thinking, social change, and innovation.

A modern cultural renaissance in Pakistan would revive the spirit of artistic freedom. It would encourage artists, writers, and intellectuals to challenge the systems and question the norms without fear of censorship or punishment. Public support for artistic work through grants and initiatives would nourish this creative spirit. Cities could have open-air art exhibitions, street performances, and community-driven festivals to bring art to the public and encourage grassroots participation in cultural dialogue.

Technology would be a game changer in this revival. With digital tools democratizing creative platforms, artists and writers can bypass the traditional gatekeepers and reach a wider audience. Social media, streaming platforms, and digital art forms can amplify the progressive voices and bring Pakistani culture to the world.

Inclusivity should be the foundation of this renaissance. Marginalized groups like women, minorities, and youth should have a bigger presence in the cultural narrative. Their stories and perspectives are key to creating a diverse, authentic, and lively cultural identity for Pakistan.

Education is the answer to any such movement. By including arts and humanities in school curriculums, the next generation can be active players in this revival. Universities can have artist residencies, literary festivals, and public lectures to bridge the gap between academia and creative industries and create space for intellectual and artistic growth.

With collective effort and imagination Pakistan can once again be the hotbed of cultural innovation and progressive thought.

Conclusion

In the early days of Pakistan, people, through their social activism made possible a more progressive, inclusive, and creatively alive society. Even their radicalism was not merely an aesthetic choice but a commitment to social justice, gender equality, and political freedom.

Yet, the progressive ideals of those icons were pushed aside. Conservatism and religious orthodoxy have kind of taken over the cultural narrative of Pakistan. The regressive trends in Pakistani drama, media, and public discourse indicate that we are actually moving away from the values of critical thinking and societal progress that had once defined our cultural identity.

So, let’s learn from the past and reclaim the bold progressive Pakistan of our artistic and intellectual heritage. Only then we can inspire the same kind of change that our cultural icons fought for with such bravery.

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please check the Submissions page.

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.

Momina Areej is currently pursuing an MPhil in Clinical Pharmacy Practice. With a passion for writing, she covers diverse topics including world issues, literature reviews, and poetry, bringing insightful perspectives to each subject. Her writing blends critical analysis with creative expression, reflecting her broad interests and academic background.