Introduction

In explaining the extent of the success of the anti-nuclear movements in the Global South, the paper will aim to explain how they have linked the topic of nuclear weapons to topics such as decolonization, social justice, racial equality, and environmental justice which also helped the movement gain more international momentum. The paper will prove that, contrary to the popular belief that the Global South had been passive in the injustices made against them by the West, powerful movements have been formed in Africa and other regions in the Global South.

This is precisely the reason this paper will focus on the Global South’s agency in the global norm against nuclear weapons, particularly because they were the main victims of nuclear testing and imperialism (Allman, 2008: 86), and therefore had the most stakes in raising awareness and changing policy towards nuclear weapons. The agency of these movements has provided great momentum to the anti-nuclear sentiment globally and proves the power of the agency of such movements on policymaking.

The role and successes of several Global South anti-nuclear movements will be analyzed in this paper, including the Sahara Protest Team, the African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (Pelindaba Treaty), Partisans of Peace, and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. Other than secondary sources of academic literature, the paper will explore a number of primary sources including newspapers, speeches, letters and treaties.

The Sahara Protest Team and the Pan-African Struggle Against Nuclear Testing

An important phenomenon that does not have enough light shed on regarding Pan-Africanism is the link between the Pan-African struggle for independence and the opposition to nuclear armament. The Pan-African struggle was not only against the conventional form of imperialism but also nuclear imperialism in the 1950s and 1960s (Allman, 2008: 83). Nuclear imperialism refers to the nuclear world order, where the centre continuously exploits and subjugates the periphery.

The periphery is exploited for its raw materials that are used for nuclear power under the façade of ‘civil nuclear cooperation’ by core states. The core also uses nuclear threats and terrorism against the periphery (in particular, nuclear testing on the periphery’s land) while leading the non-proliferation regime of the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) that pressures the periphery to join and disarm or else stigmatized and punished (Hussain & Zuhoor, 2019: 74-75).

Discussing the role that the Pan-African movements have had on the issues of nuclear testing is of paramount importance as it goes to dispel what has been termed ‘afro-pessimism’, which is the notion that “nothing good ever comes out of Africa” (as cited in Allman, 2008: 84). Not only does the movement of the Sahara Protest Team link the anti-colonial struggle with anti-nuclearism but it also connects these notions with racial justice through its ability to garner support and alliance with black people, not only in Africa but also in the US.

This is referred to as Black internationalism (Allman, 2008: 85). As black internationalism was growing, along with anti-colonial movements in Africa, France announced its intentions in 1958 to use Algeria’s land for testing a new atomic bomb. The Algerian nationalists passed a resolution denouncing the decision to use Africa for nuclear tests, yet to no avail (Allman, 2008: 87).

On April 22 in 1958 in Accra, the First Conference of Independent African States was held to appeal to the Western powers to halt the production and testing of nuclear weapons, with a particular condemnation of French intentions to test nuclear weapons in Algeria. As this was not only an effort against nuclear imperialism, and rather tied nuclear imperialism to other forces of imperialism, part of the resolution brought up the Palestinian problem, urging for a just solution (Loves, 1958).

The Pan-African movement against nuclear imperialism encompassed all forms of oppression by the West and strived for the emancipation of all oppressed peoples. As Ghana provided an independent and transnational forum for black people, influential radical black activists travelled to Ghana to join the protest against French nuclear testing.

Along with Kwame Nkrumah, protestors like Rustin, Sutherland, Scott, Randle, and others, decided to meet in Accra and then drive to the test site in Algeria to protest against it. This protest was fully supported by Ghana’s ruling party at the time and provided the Ghana Council for Nuclear Disarmament (GCND) with G£2,757 (Allman, 2008: 90).

The team of protestors was ready to take on what they knew would be a difficult journey with the support of the Ghanian government. The African peoples and the government of Ghana both showed great enthusiasm, determination, and the will to stand up against racial injustice and nuclear imperialism despite great obstacles in their way. In no way shape or form were they simply passive and accepting of the great injustices done against them.

“We are going to see that we create our own African personality and identity. We again rededicate ourselves in the struggle to emancipate other countries in Africa; for our independence is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of the African continent,” (Nkrumah, 1957: 01:30). This quote from the speech Nkrumah made was of great significance because it highlighted the importance of African unity in the face of Western imperialism of all forms.

When the team assembled in Accra, the French authorities denied them visas for entry, including a French citizen, but that hardly put them down. At the UN, Ghana’s permanent representative said, “If France must explode its bomb, they are quite welcome to do so somewhere in metropolitan France…….. Those days when the destiny of Africa was decided at the conference tables outside Africa…… are over,’’ (as cited in Allman, 2008: 91).

On December 5, 1959, the team of 18 protestors assembled in Accra and began their journey to head to the nuclear testing site in Algeria. When they reached the first French government post at Bittou, they were stopped by French officers and told they were given orders to not allow them through. They spent several days in limbo but eventually had to withdraw and reconsider their plan.

They headed toward Po in the Upper Volt and were once again stopped at the frontier post. They were then arrested and driven to Ghana where they were unceremoniously dumped. On February 13, 1960, France dropped its first nuclear bomb in the Sahara Desert and on April 1, it dropped its second bomb (Allman, 2008: 90-92).

Was it Worth the Try?

Although it came as a crushing disappointment to the Sahara Protest Team and the Ghanian party who invested great time, effort and money to stop the bombs from being dropped on African soil, as well as to all the oppressed African peoples, it nonetheless stands for black and African solidarity and determination to stand up against injustice, to refuse being silenced and stifled by their white oppressors.

The joining together of African liberation forces, US civil rights movements and European anti-nuclear forces were believed to have helped feed and reinforce each other positively in addition to the fact that the movement was supported by the Ghanian political party which marked a pivotal point in progressive history (Allman, 2008: 97).

This protest, furthermore, marks the ability to connect the national to the international and the global. Decolonization projects should not only be viewed as national or domestic endeavors, but rather as an international endeavor to achieve racial equality across the globe. It should be regarded as a new vision or a reimagining of the world marked by justice and equality.

These efforts have demanded the reconstruction of the international order (Getachew, 2019: 2-5). The movement, despite not being able to achieve what it had initially assembled to do, still stood for something greater. The topic of nuclearism had become a taboo by then, which has a considerable impact on how nuclear weapons are viewed and thus dealt with.

It was a transnational movement, a movement that gathered black people from all over the world, to stand together for the freedom they believed in. It was by then proved that great things can and do come out of Africa, but when those impactful things do come out of Africa, they are made to be hidden or reframed to be made irrelevant.

Take, for example, the Atoms for Peace speech made by Eisenhower right after a nuclear testing bomb was dropped on the bikini atoll in the marshall islands in 1954, a bomb that was 1000 times more destructive than the one dropped on Hiroshima (Krige, 2006: 163). If you search for ‘Atoms for Peace’, you will find tens of thousands of relevant sources for that one speech Eisenhower made that was meant to make the US look good, despite, once again, the irony of the timing of the speech.

On the other hand, trying to find literature on the Sahara Protest Team and Kwame Nkrumah’s speeches about the movement is very difficult as the sources are much more limited. ‘Afro-pessimism’ can therefore be said to be nothing more than a Western construct deliberately made not only to paint a negative image of Africa to the world but also to lower African morale in regard to their unlimited potential.

The desire to make Africa free of nuclear oppression did not stop with the dissolution of the Sahara Protest team. In 1964, 33 African states at the UN Assembly asked to place on the agenda the banning of nuclear weapons in Africa (The Washington Post, 1964). That year, the African Weapon-Free-Zone Treaty was proposed (Security Dialogue, 1996: 233).

Many of the African states were not just preventing nuclear testing on their grounds by the West but were also not interested in acquiring nuclear weapons as Kwameh expressed, “We have to prove that greatness is not to be measured in stockpiles of atom bombs” (Kwameh, 1961).

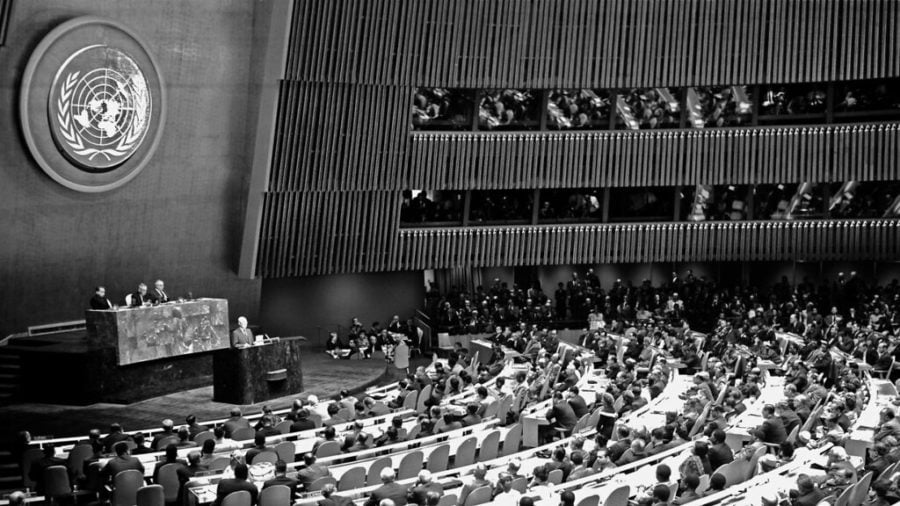

In 1996, a great achievement was accomplished; the UN General Assembly adopted the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) which was opened for signature by all states. It maintained that all signatories were banned from any nuclear weapon test explosion or nuclear explosion and to prohibit any nuclear explosion in any area under its jurisdiction.

The African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (Pelindaba Treaty)

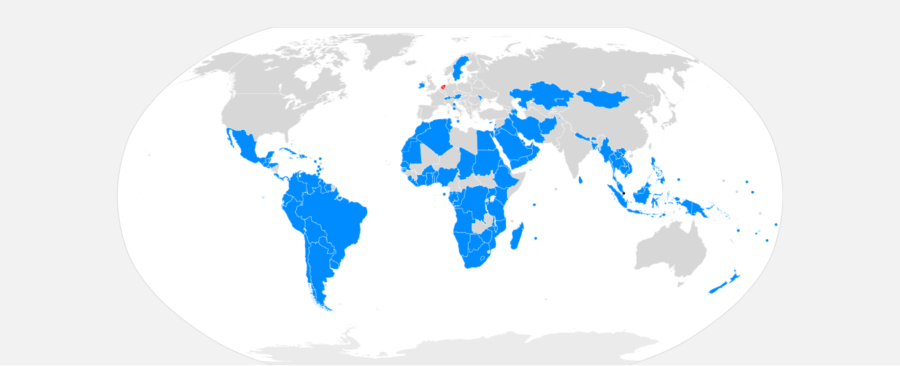

In 1996, African heads of state met in Cairo to participate in the signing of the Pelindaba Treaty which marked Africa’s impactful step towards a nuclear-weapon-free zone among African states. The African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (NWFZ) is the third such zone established, with the other two existing in Latin America and the South Pacific (Ogunbanwo, 1996: 185).

This treaty was made with the conviction that the African NWFZ would provide an important step towards the reinforcement of the non-proliferation regime and the promotion of complete disarmament to enhance regional and international peace and security. The aim of this treaty was also to protect African states from potential nuclear attacks.

Furthermore, the concerted effort at making Africa nuclear-weapon-free is also to protect its land from environmental pollution caused by radioactive waste and matter (Pelindaba Treaty, 1996). The aforementioned aims are all of great importance, not only to Africa but to the world.

The creation of such a treaty provides the acknowledgement that although nuclear weapons provide ‘deterrence’ as Nuclear Weapons States (NWS) argue (Waltz, 1990: 733), the majority of other heads of state are more than willing to dispense with them due to their destructive and harmful forces.

Protocol I of the treaty provides negative security assurance, which is the undertaking of protocol party states not to use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against the parties to the treaty (Ogunbanwo, 1996: 185). This protocol was open for signature by China, the UK, the US, Russia, France and Northern Ireland.

Article 5 of the treaty prohibits the testing of nuclear explosive devices by any state anywhere in Africa (Pelindaba Treaty, 1996). This meant a great success in the creation of a nuclear-free Africa where nuclear testing by Western NWS was no longer an option. Furthermore, to help Africa make the best use of nuclear energy, Article 8 of the treaty provides that nuclear science and technology can be used for peaceful purposes.

As a significant upgrade to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the Pelindaba Treaty makes no room for loopholes in the treaty by agreeing to the term ‘nuclear explosive device’ instead of ‘nuclear weapon’ as it is in the NPT (Ogunbanwo, 1996: 190). Article 1 of the treaty defines the ‘nuclear explosive device’ as “means any nuclear weapon or other explosive device capable of releasing nuclear energy, irrespective of the purpose for which it could be used” (Pelindaba Treaty, 1996).

The ban on nuclear explosive devices also includes a ban on peaceful nuclear explosives (Ogunbanwo, 1996: 191), which signifies the treaty’s concern for environmental protection.

The Nuclear Weapons Free Zones: Towards Global Nuclear Disarmament?

“Although the total abolition of nuclear weapons seems, at present, to be quite difficult, promoting Nuclear Weapons Free Zones (NWFZs) from a regional standpoint might encourage further large-scale non-proliferation processes” (Mukai, 2005: 79). Nuclear Weapons Free Zones offer the anti-nuclear, nonproliferation regime a number of advantages.

As mentioned earlier, the Pelindaba Treaty was deliberate in meticulously defining nuclear explosive devices, as has the Latin American NWFZ in order to completely avoid any potential loopholes. Furthermore, the NWFZ treaties explicitly maintain the prohibition of stationing nuclear weapons or nuclear explosive devices, unlike article 2 of the NPT which does not prohibit such thing. Thus, NFWZ provide a stronger commitment to non-proliferation than the NPT (Mukai, 2005: 80).

It is argued that it would be very difficult, if not impossible, to aim at the goal of achieving global disarmament by beginning with this issue globally. By all means, having NWFZ is a great step forward. It fosters an environment against nuclear weapons as well as provides people in the region the safety from nuclear threats. However, it is yet important to question the viability of regarding NWFZ as the only way to initiate complete and global disarmament.

If anything, the NPT which they created and crafted suits their interests of ensuring that no other state enjoys the ‘privilege’ of possessing nuclear weapons but themselves. The controversial Article 6 of the NPT which has angered many Non-Nuclear Weapons States (NNWS) provides NWS with the loophole of vertical proliferation while prohibiting horizontal proliferation. Many find the NPT to exhibit double standards and nuclear imperialism (Jayaprakash, 2008: 43).

Therefore, they took it upon themselves to create an equal non-proliferation treaty without the double-standard dictates of the NPT. Sure, creating a NWFZ provides the equality that should exist in such an agreement, but to what extent can we say that this step is going to eventually disarm the NWS? If anything, can we not argue that this could further fetishize nuclear weapons, and further reinforce the notion of elitism of nuclear weapons holders?

The point here is not to say that other states should possess nuclear weapons because it would be unfair for some to have the elite status of being holders of such status symbols. No state should have in its possession and its disposal the capacity to destroy and kill in the most heinous ways, and leave generations to come to suffer from the aftermath of an event they never wanted part in.

The point is to question the presumption that NFWZ will actually result in global disarmament because it is easier to ‘work its way up’, as was Mukai’s (2005) understanding of it. But NPT never really had to ‘work its way up’. Signatories to the treaty, other than NWS, are all prohibited from producing or possessing nuclear weapons (Bajia, 1997: 48). It certainly is, though, easy to criticize than to come up with viable alternatives.

The Peace Partisans

In 1949 at the Paris Congress, the term Peace Partisans was first heard from the World Peace Congress. It is an anti-nuclear pacifist movement initiated under the World Peace Congress. Its roots lie in the anti-Fascist movement of the 1930s and Leninist teachings in which the Communist Party was involved (McLachlan, 1951: 10-12). It was a protest against American aggression, capitalism and imperialism (Warren, 1949).

Furthermore, the movement aimed to rally support for Russia against the Atlantic pact’s alleged plans for war on Russia. William Dubois, a civil rights activist, spoke at the Paris conference and described US’s policies as a form of new colonialism, on which he blamed the basic cause of war trends. He described the US as the forefront of the re-enslavement of human labor (New York Times, 1949).

Another prominent figure and Soviet writer, Ilya Ehrenburg, directed the following words at the US, “You can’t do two things at once-talk of peace and take an atomic bomb from your pocket” (as cited in Warren, 1949). At the conference, the Peace Partisans also demanded outlawing of atomic bombs and the boycott of all propaganda in favor of a new war (The Washington Post, 1949).

By August 1950, Peace Partisans came forward with the Stockholm Appeal petition that would outlaw the atomic bomb. 273,470,566 people signed the appeal all over the world, including in the US and Europe (New York Times, 1950). Despite beginning as a pro-Communist, Russian group, the Peace Partisans over time was not just a fight against the US.

J.D Bernal, Chairman of the Presidential Committee of the World Peace Congress, wrote a letter responding to criticisms aimed at the World Peace Congress due to it being dominated by the Soviet Union by writing, “[The World Council for Peace] was the first international body which campaigned against nuclear weapons…..For years it has advocated the cause of total and controlled disarmament. Its present initiative is one which is called for by the need to find some expression of world public opinion during the session of the 17-nation Disarmament Committee in Geneva” (Bernal, 1962).

In Bernal’s ‘Appeal’, he also wrote the following: “We invite all organisations and movements, all men and women concerned with ending the present dangers and who are working towards his great goal, to participate in our Congress. All are welcome. There we can have a free and frank discussion of every problem related to peace and disarmament. There are indeed no vital questions, whether national independence, living standards, or employment, that are not directly affected by the present arms race. All need to be discussed in relation to disarmament.” (Bernal, 1962).

This text makes clear the connection that the movement makes between nuclear imperialism and problems of independence and even livelihood, which could have possibly been the source of the vast support it received from all over the world, particularly from the Global South that was struggling with issues of national independence at the time. One of the major supporters from the Middle East at the time was the United Arab Republic.

In 1962, when Anwar al-Sadat was president of the National Assembly and the Afro-Asian Committee, he wrote a letter to Bernal in support of the movement saying, “I would like to inform you that we, the United Arab Republic, are convinced that the problem of general and total disarmament under effective international control is the hope of millions of people who want to put an end to the danger of nuclear war in our world…..I am convinced that general and total disarmament, once achieved, will be a heavy blow against colonialism and its aggressive designs” (Sadat, 1962).

In Egypt, the movement had its branch (the Partisans of Peace Movement) and gained a lot of attention from artists, actors, writers and journalists who promoted the movement and its ideas. Another branch was also in Syria (the Syrian Partisans of Peace). Both branches made concerted efforts to persuade politicians to sign the Stockholm Appeal.

Not only was the movement interested in denuclearization but the Partisans of Peace Movement in Egypt also played a pivotal role in the anti-British armed struggle in the Suez Canal (Ginat, 2021: 716-718). The movement then spread in Iraq after a speech Mohamed Al-Jawhari made when he was elected to the Partisans conference World Council which was held in Warsaw in 1950. He discussed the injustices imposed on Iraq by the West with their imperialism and war (Bishop, 2021: 67).

The colonized peoples were not silent. They stood up against what they believed was a great injustice to them and voiced their concerns and will to put an end to it. They did not watch idly as the West increased its nuclear capacity and oppressed them. Their agency was well and alive.

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)

The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) was an initiative made by the Global South and has been voted for adoption by 122 states in 2017 which aimed to challenge the nuclear status quo. However, only a few Western states have adopted this treaty, with the rest being rigorously against it (Acheson, 2019: 78). France, for instance, has not signed or ratified it and has continuously voted against it in the annual UN General Assembly resolution since its inception (ICAN, 2022).

The treaty provides a comprehensive plan of prohibitions against any nuclear activities, including a ban on testing, developing, acquiring, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons. Furthermore, the treaty provides that the parties must provide assistance to those who have been affected by the usage or testing of nuclear weapons as well as provide for measures to be taken for environmental remediation in areas that have been contaminated by nuclear explosives (Immenkamp, 2018: 3).

The treaty gained immense resistance, mainly from NWS, with one of the criticisms cited against the treaty being its weakness due to the fact that NWS and their allies were not involved in its drafting (Immenkamp, 2021: 5). However, this criticism is less than convincing, given that the NPT was drafted by the NWS and has hardly produced the desired result of global denuclearization. Besides, since when is a treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons meant to accommodate NWS interests in keeping their nuclear weapons?

The whole point of a treaty of this sort is precisely to abolish nuclear weapons altogether. At any rate, Acheson argues that the NWS are against the TPNW because it challenges the patriarchy in two ways: first, the initiative was brought by activists, diplomats and academics that shifted the discourse from the importance of deterrence to the urgency of disarmament; second, the treaty was promoted by the empowerment of the activists of the global south, women and diplomats (Acheson, 2019: 78).

The TPNW was dismissed by the EU as ineffective and unrealistic in the face of contemporary challenges of the international security environment, given the fact that the TPNW does not allow signatories to host nuclear weapons. This would present a significant challenge to many European countries who host US nuclear weapons as part of their security agreements. The European governments have rejected this initiative despite strong public opinion in favor of the treaty in Belgium, the Netherlands, Italy and Germany (Immenkamp, 2021: 5).

Acheson argues that despite the fact that the NWS have not joined this treaty, it still stands as an important normative force on the behavior of other states regardless of whether they sign the treaty or not. Perhaps if this theory is true, it could also hold for NWFZ. The ban also impacts financial institutions, and national and local actors, all of which bring changes to politics and economics that could eventually lead to complete nuclear disarmament (Acheson, 2021: xxii).

Furthermore, demonstrating a pronounced and complete rejection of nuclear weapons can help increase the taboo and stigma surrounding nuclear weapons. The point behind such a ban is to make research, development, testing and possession of nuclear weapons illegal, and thus increasing the political and economic costs of keeping nuclear weapons. Such a ban would impact the calculations of NWS (Acheson, 2021: 110).

As the TPNW bans the stockpiling or hosting of another state’s nuclear weapons, it renders ineffective the ‘extended nuclear deterrence’ advantage which posits that a NWS would use nuclear weapons to protect its allies. Moreover, the ban would also incur domestic political costs for politicians who oppose the ban as they would have to justify their position in an environment that is increasingly anti-nuclear and views it as illegal, and even immoral (Acheson, 2021: 112).

Conclusion

The Global South anti-nuclear movements have not come without their challenges and limitations. Nonetheless, they have proven the Global South to be fully capable of asserting their agency, their voices and their opinions on a matter that affects not only them but the whole world.

Movements such as the Sahara Protest Team, despite being incapable of stopping the French nuclear tests in Algeria, has nonetheless left a legacy of Pan-African resistance, resilience and determination to stand in the face of their oppressors. It has brought light to the matter of racial injustice and imperialism of nuclear weapons.

Although it happened 38 years after the protest, nuclear weapons test explosions were banned by the CTBT. NWFZ in Africa, and elsewhere, have also been influential in fostering a climate that increasingly criminalizes the development and possession of nuclear weapons as well as ensuring the denuclearization and non-proliferation in vast regions, not only in Africa, but also in Latin America and the South Pacific (Ogunbanwo, 1996: 185).

Peace Partisans movement also demonstrated the immense support Global South states have given to the non-proliferation regime. And finally, the NPTW led by the Global South, despite not being signed NWS yet, is still believed to be incremental in providing a possible future without nuclear weapons (Acheson, 2021: xxii). Furthermore, the treaties discussed in this essay also provided viable alternatives to the NPT.

The movements encouraged activism against nuclear weapons, and such a matter was not just the domain of powerful governments. All of these accomplishments of the Global South demonstrate the determination of those states of creating a safer, more socially and racially just and clean environment for the whole world, despite the common misconception and portrayal of the Global South being passive receivers of bad ends of White deals. Thanks to their efforts and accomplishments, a possible nuclear-free world can be imagined.

References

- Acheson, R. (2019) The nuclear ban and the patriarchy: a feminist analysis of opposition to prohibiting nuclear weapons, Critical Studies on Security, 7:1, 78-82.

- Allman, J. (2008) Nuclear Imperialism and the Pan-African Struggle for Peace and Freedom: Ghana, 1959–1962 , Souls, 10:2, 83-102.

- Bajia, S. (1997). The Concept of Nuclear Proliferation: Need For Reconsideration. Indian Journal of Asian Affairs, 10(1), 47–50.

- Bernal, D. “To Ease the Tension”. (1962, May 31). Marx Memorial Library. https://www.marx-memorial-library.org.uk/project/jd-bernal/world-congress-general-disarmament-and-peace

- Bernal, D. “World Congress for General Disarmament and Peace Appeal”. (1962, January 29). World Council of Peace, London. Marx Memorial Library. https://www.marx-memorial-library.org.uk/project/jd-bernal/world-congress-general-disarmament-and-peace

- Bishop, E. (2021). The “Partisans of Peace” between Baku and Moscow: The Soviet Experience of 1958. In J.G. Karam (Authors), The Middle East in 1958: Reimagining a RevolutionaryYear (pp. 65–76). London: I.B. Tauris.

- The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test Ban Treaty. (1996). Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Preparatory Commission.

- France and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. ICAN. (n.d.). Retrieved May 20, 2022, from https://www.icanw.org/france

- Getachew, A. (2019). Worldmaking after empire: The rise and fall of self-determination. Princeton University Press.

- Ginat, R. (2021) Egyptian communist voices of peace (1947–1958), Israel Affairs, 27:4, 711-731.

- Herald, T. (1964, September 18). African Nations Ask Nuclear Ban,” The Washington Post.

- Hussain, N. & Zuhoor, S. (2019). Determinants of the US nuclear imperialism: A theoretical analysis. Margalla Papers, 2, 71-84.

- Immenkamp, B. (2021). Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons ─ The ‘Ban Treaty’. European Parliamentary Research Service.

- International Propaganda Organ is Created as World Peace Congress Ends in Paris. (1949, April 26). The Washington Post, 6.

- Jayaprakash, D. (2008). Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: The “Greatest Con Game.” Economic and Political Weekly, 43(32), 43–45.

- Krige, J. (2006). Atoms for Peace, Scientific Internationalism, and Scientific Intelligence. Osiris, 21(1), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1086/507140

- Kwameh, N. (1957, March 5). Independence Speech. [Speech Audio Recording]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=knrFJMhjB_0

- Kwameh, N. “I Speak of Freedom.” 1 January 1961. Fordham University, https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/mod/1961nkrumah.asp

- Loves, K. (1958, April 23). ‘‘African Nations Ask Nuclear Ban,’’ New York Times.

- McLachlan, D. H. (1951). The Partisans of Peace. International Affairs (Royal Institute of International Affairs 1944-), 27(1), 10–17.

- Mukai, W. (2005). The importance of Nuclear Weapons Free Zones. ISYP Journal on Science and World Affairs, 1(2), 79-86.

- Ogunbanwo, S. 1996. The Treaty of Pelindaba: Africa is Nuclear-Weapon-Free. Security Dialogue, 27(2), 185-200.

- Paris Degree Bars Parade for ‘Peace’. (1949, April 23). New York Times, 2.

- Peace Partisans Listed: Red-Led Group Says 273, 470, 566 Sign ‘Stockholm Appeal’. (1950, August 10). New York Times, 3.

- Sadat, A. Letter to J. D Bernal. (1962, May 10). Marx Memorial Library. https://www.marx-memorial-library.org.uk/project/jd-bernal/world-congress-general-disarmament-and-peace

- The African Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty (The Treaty Of Pelindaba). (1996). Security Dialogue, 27(2), 233–240.

- The African Weapon-Free-Zone Treaty (Pelindaba Treaty). (April 11, 1966). African Union. The Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. (1996). Preparatory Commission for the

- Waltz, K. (1990). Nuclear Myths and Political Realities. The American Political Science Review, 84(3), 731–745.

- Warren, L. (1949, April 21). Paris ‘Peace Congress’ Assails on US and Atlantic Pact, Upholding Soviet. New York Times, 1.

- Warren, L. (1949, April 21). West Again Scored at Paris Congress. New York Times, 9.

If you want to submit your articles, research papers, and book reviews, please check the Submissions page.

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.