Introduction

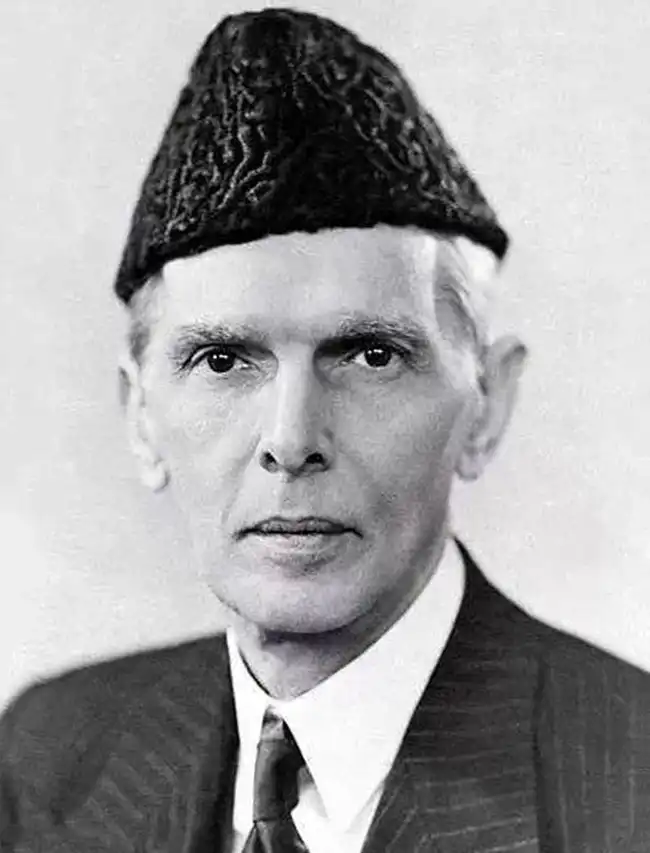

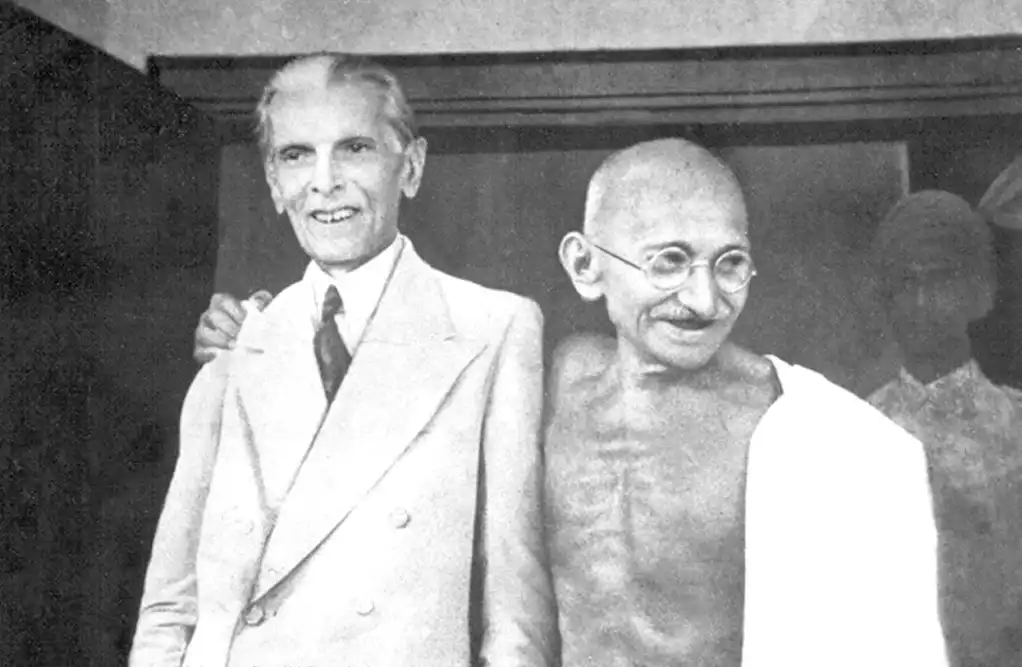

In September 1944, two of India’s most prominent leaders, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi and Muhammad Ali Jinnah (RH), met in Bombay for a series of in-depth discussions. These meetings were significant given India’s tense political situation. The country was moving towards independence but faced a deep division over its future shape and the relationship between its two main communities.

The political landscape was defined by key disagreements. Jinnah, representing the All-India Muslim League (AIML), firmly advocated for the creation of independent, Muslim-majority states, based on the Lahore Resolution of 1940 and the belief that Muslims were a separate nation (the two-nation theory) (Hamdani, 2020, p. 172). This stance had garnered significant support among Indian Muslims. Conversely, the Indian National Congress and leaders like Gandhi fundamentally rejected the two-nation theory and aimed for a united India, exploring ways to accommodate Muslim concerns within that framework. This fundamental difference created a major political deadlock between the two main parties. The Jinnah-Gandhi talks of 1944 were a direct attempt to bridge this divide and find a pathway forward.

Backdrop of the Jinnah-Gandhi Talks

The backdrop to these talks included earlier attempts to bridge the communal divide. A major political vacuum emerged in August 1942 after Congress launched its “Quit India Movement,” leading to the swift arrest of Gandhi and the entire Congress Working Committee on August 9th. Into this void stepped senior Congress Figure C. Rajagopalachari (Rajaji), who actively sought a resolution while the main leadership was imprisoned. As early as April 1942, Rajaji had persuaded Congress legislators in the Madras presidency to pass resolutions recommending that the All-India Congress Committee (AICC) accept the Muslim demand for partition in principle. However, these recommendations were firmly rejected by the AICC later that month, as it deemed any proposal to divide India detrimental (Singh, 2009, p. 286).

Undeterred, Rajaji continued his efforts. Around February 1943, while Gandhi was still imprisoned, Rajaji discussed the Pakistan question with him and secured Gandhi’s consent for a more developed, multi-point formula. This proposal evolved further. On April 8, 1944, Rajaji formally presented this “Rajaji Formula” (or “C.R. Formula”) to Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Khaliquzzaman, 1961, p. 282).

The core tenets of the Rajaji Formula presented to Jinnah in April 1944 proposed (Khaliquzzaman, 1961, p. 282):

- The Muslim League would first endorse India’s pursuit of independence and join Congress in a provisional interim government.

- Following the war, a special commission would identify and demarcate contiguous districts in the northwest and east where Muslims formed an absolute majority.

- Then a plebiscite involving all residents of these demarcated areas would determine if they wished to separate from Hindustan.

- Should separation be the outcome, mutual agreements would be established to manage essential matters like defence, commerce, and communications.

- Any transfer of population between the new entities would be entirely voluntary.

- Finally, the entire agreement would only come into effect once Britain fully transferred power and responsibility for governing India.

Jinnah, however, did not approve or accept the formula when Rajaji presented it in April 1944, reportedly feeling it was offered on a “take it, or leave it” basis, which he considered “pure and simple dictation.” He famously characterized it as a “parody and negation of Pakistan,” arguing vehemently that it fundamentally failed to meet the League’s demand as per the Lahore Resolution (Allana, 1967, p. 247). While Jinnah later clarified he would have been willing to place the formula before the Muslim League Working Committee had he been permitted by Rajaji or if Gandhi sent it directly, his stance against the formula’s substance, particularly as it came from Rajaji who lacked official Congress backing, was unmistakably clear: it was unacceptable as a basis for settlement (Ravoof, 1955, p. 72).

Despite Jinnah’s prior rejection of the formula when presented by Rajaji, and the fact that other key Congress leaders like Nehru did not accept it (with the Bengal Congress conference and the Hindu Mahasabha also condemning it) (Abid & Abid, 2008, p. 52), Gandhi, released from jail on May 6, 1944, due to deteriorating health (following an earlier 21-day fast in 1943), personally endorsed this very formula. He saw it as a potential basis for negotiation and decided to initiate direct talks with Jinnah, hoping to convince him to accept it as a pathway to a settlement.

Gandhi initiated contact by writing to Jinnah on July 17, 1944. Choosing to write in Gujarati, their shared mother tongue, he addressed Jinnah warmly as “Brother Jinnah” and signed off as “Your brother, Gandhi.” Gandhi expressed his long-held view of being a “friend and servant” to Jinnah and the Muslim community. He urged Jinnah not to see him as an enemy but as a friend. He asked to be invited whenever Jinnah was ready and added, “Do not disappoint me” (Hamdani, 2020, p. 171).

Jinnah replied relatively quickly, on July 24th from Srinagar. His reply was formal, in English and addressing Gandhi as “Dear Mr. Gandhi,” and stated that he would be glad to receive him at his Bombay residence upon his return in mid-August (Hamdani, 2020, p. 171).

The Dialogue Begins

The talks began on 9th September 1944, at Jinnah’s Bombay residence. They would continue for a further 18 days to conclude on September 27th. The negotiations were both face to face as well as through correspondence, as preferred by Jinnah, who wanted to ensure clarity and maintain a precise record of each leader’s position (Bolitho, 1953, p. 148).

Initially, the meeting started warmly with warm personal gestures. Reports mention handshakes and embraces at their first meeting, suggesting a genuine human connection between the two. Jinnah personally came out to greet Gandhi and even allowed them to be photographed together. During the duration of prolonged talks, Gandhi sent special food to Jinnah and even his “nature cure doctor” to give Jinnah massages since Jinnah wasn’t in the best of health (Singh, 2009, pp. 298-300).

However, despite these benevolent gestures, the depth of the disagreement between the two became clear quickly. The main points where both of them fundamentally disagreed with each other were:

1. Who Was Representing Whom?

From the start, Jinnah insisted on a framework for the talks. He argued that Gandhi MUST come to the table as a representative of the Hindus and the Indian National Congress, just as Jinnah represented the All India Muslim League and the Muslims, for any meaningful outcome. This was particularly pertinent given that the formula under discussion (Rajaji Formula) lacked official Congress endorsement (with most of the Congress Working Committee still imprisoned) and had already been criticized by Jinnah when presented by Rajaji.

Jinnah believed that the Muslim League was the “sole voice” of the Muslims of India; meanwhile, Gandhi stated he was meeting Jinnah in his individual capacity and was not there on behalf of the Indian National Congress. Gandhi explained that he had openly said he represented no one in this private meeting. Jinnah found this to be unacceptable and “extraordinary.” Jinnah felt as though this created an uneven playing field since any agreement between them would be binding on Jinnah and the League, but since Gandhi could only offer personal recommendations to the Congress, potentially not binding them to the agreement (Nanda, 2010, p. 310).

2. The Basis for a Settlement: One Nation or Two?

Jinnah’s main demand was based on the Lahore Resolution of 1940. He insisted that Gandhi must first accept the two-nation theory and the core belief that Hindus and Muslims were two major nations in India, distinct from each other. Only after accepting this could they discuss the details. Gandhi instead rejected the idea of Muslims and Hindus being two separate nations. While Gandhi was willing to discuss the Rajaji Formula’s idea of self-determination for the Muslim majority areas, after gaining independence, Jinnah viewed this formula with deep distrust.

He reiterated strong objections he had voiced months earlier, particularly criticizing the proposal for a plebiscite involving all residents (not just Muslims) in the demarcated areas and what he considered its other vague and unsatisfactory terms. Jinnah saw Gandhi’s insistence on these aspects of the formula, especially the inclusive plebiscite, as an attempt to undermine the very concept of Pakistan (Ali, 1967, p. 39).

3. What Should Happen First, Independence or Separation?

Another contentious issue between them was the order of events. Gandhi believed that the top priority should be for the League and the Congress to unite now to achieve independence. Gandhi believed Hindu-Muslim unity was key to doing this. Jinnah, however, argued that the recognition of Muslims as a separate nation and the principle of partition had to be accepted first. Only then could cooperation towards independence meaningfully happen (Nanda, 2010, p. 311).

Why Did the Talks Fail?

The talks became increasingly difficult due to these fundamental differences. Jinnah found Gandhi to be “too technical” (Allana, 1967, p. 248), while Gandhi later called the discussions a “test of my patience” and “most disappointing” (Singh, 2009, p. 300). The conversations seemed to be running on “parallel courses” and never truly meeting for a meaningful settlement. Jinnah felt he had failed to “convert Mr. Gandhi” (Allana, 1967, p. 248), while Gandhi observed that Jinnah seemed to want him to simply agree and “join the band of the faithful” (Singh, 2009, p. 300).

A personal story during these times comes from Kanji Dwarkadas, who met Jinnah shortly after the talks concluded. Dwarkadas mentioned that thirteen days after the talks had ended with Gandhi, he found Jinnah to be unwell, weak, and feeling low. Jinnah spoke softly, and Dwarkadas could barely understand what Jinnah was saying. He heard Jinnah whisper: “Why did Gandhi come to see me if he had nothing better to offer?” This sentiment perhaps reflected Jinnah’s frustration that Gandhi was reiterating a formula he had already found inadequate.

When Dwarkadas asked whether Jinnah found that Gandhi intended to make him look bad publicly, Jinnah surprisingly responded, “No, no. Gandhi was very frank with me and we had very good talks.” This exchange suggests Jinnah’s internal disappointment for lack of substantive new proposals from Gandhi to address his demands (Bolitho, 1953, p. 151).

After eighteen days of intense discussions and exchanges of letters, it was now clear that they couldn’t find any agreement. The talks ended on September 27, 1944, and the public was officially informed of this fact, with the letters being made public to the press. At a press conference, Jinnah directly stated that it was “not possible to reach an agreement with Gandhi.” Meanwhile, Gandhi tried to maintain some optimism and called the breakdown “only so-called,” describing it as a pause and expressing hope to meet again in the future (Allana, 1967, p. 252).

The main reasons for the failure were precisely the fundamental disagreements they couldn’t overcome: Gandhi’s rejection of the two-nation Theory, his condition that a vote on separation include all communities (a key feature of the Rajaji Formula that Jinnah had consistently opposed), meanwhile Jinnah’s insistence that Gandhi negotiate as a formal representative, which Gandhi refused. They simply couldn’t find a way to bridge the gap between Jinnah’s demand for a sovereign Pakistan based on the Lahore Resolution and Gandhi’s proposal for limited self-determination within some form of unified India, a proposal Jinnah had already deemed insufficient when presented earlier by Rajaji.

Conclusion

The direct consequences of the talks meant no immediate settlement in any form between the two largest political parties in India. The meetings boosted Jinnah’s profile as they indirectly accepted him to be the “sole voice” of the Muslims of India, who would represent their interests at the highest level, which greatly increased his standing and influence further. The published letters from the talks allowed a more refined version of the Pakistan demand to come forward from the league and confirmed the depth of the divide.

The British Viceroy (the highest British official in India), Lord Wavell, was unimpressed by the talks’ outcome. He famously called them a display of “complete futility” and a “deplorable exposure of Indian leadership,” comparing the meeting of the two leaders to “two great mountains” from which “not even a ridiculous mouse has emerged” (Singh, 2009, p. 511). While the talks broke down, many in the nationalist press criticized Jinnah. However, some contemporaries also suggested that aspects of Gandhi’s approach, such as his insistence on acting only in a personal capacity (especially given the formula’s lack of broad Congress support with key leaders imprisoned or unaligned with the formula) and his refusal to accept the premise of two nations, also contributed to the deadlock (Ravoof, 1955, pp. 72-73).

References

- Abid, S. Qalb-i, and Massarrat Abid. Muslim League, Jinnah, and the Hindu Mahasabha. J.R.S. Publisher, 2008.

- Ali, Chaudhri Muhammad. The Emergence of Pakistan. Columbia University Press, 1967.Allana, G. Quaid-e-

- Azam Jinnah: The Story of a Nation. Ferozsons, 1967.

- Bolitho, Hector. Jinnah: Creator of Pakistan. John Murray, 1953.

- Hamdani, Yasser Latif. Jinnah: A Life. Pan Macmillan India, 2020.

- Khaliquzzaman, Chaudhry. Pathway to Pakistan. Longmans, 1961.

- Nanda, B. R. Road to Pakistan: The Life and Times of Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah. Routledge, 2010.

- Ravoof, A. A. Meet Mr. Jinnah. Muhammad Ashraf, 1955.

- Singh, Jaswant. Jinnah: India, Partition, Independence. Rupa & Company, 2009.

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please visit the Submissions page.

To stay updated with the latest jobs, CSS news, internships, scholarships, and current affairs articles, join our Community Forum!

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm