Introduction

In an era of rapid digitization, where artificial intelligence (AI) continues to seep into every facet of our lives, there are growing concerns that the absence of proper regulation of such technologies may cause more damage than the potential benefits they offer. The dangers posed by AI in this regard disproportionately affect women compared to their male counterparts.

From exhibiting gender bias to facing repercussions of breaches of data privacy and security, women are rendered increasingly vulnerable in today’s technology-driven age. This challenge is further heightened for women in APAC countries, in particular, Southeast Asian countries, where age-old societal prejudices still wield significant influence.

AI Bias

AI utilizes data, statistical analysis, and human-created hypotheses to achieve specific outcomes. The operation of AI hinges on the data fed to it, which primarily influences the outputs it generates. AI, just like the data it’s fed, is neither immune nor exempt from human bias, and as a result, its decisions are also prone to the same bias.

In recent years, there have been numerous reports of AI bias that have had a direct and adverse impact on the rights of women. Such AI biases are a much more significant concern than human bias, as AI not only has the potential to exacerbate these biases but also carries far-reaching consequences beyond those of human actions.

Amazon AI Recruitment Tool

In 2015, the machine-learning specialists at Amazon discovered that the AI algorithm employed by the company as its recruiting engine ‘did not like women’. The data provided to the AI tool limned the domination of men, leading to the software teaching itself that men were preferable. This had the effect of penalizing resumes that had mentioned the word “women’s”.

Although Amazon corrected this bias, there was no assurance that the software would not showcase some other forms of bias in the recruitment process, ultimately resulting in the discontinuation of the AI tool.

Apple Credit Card

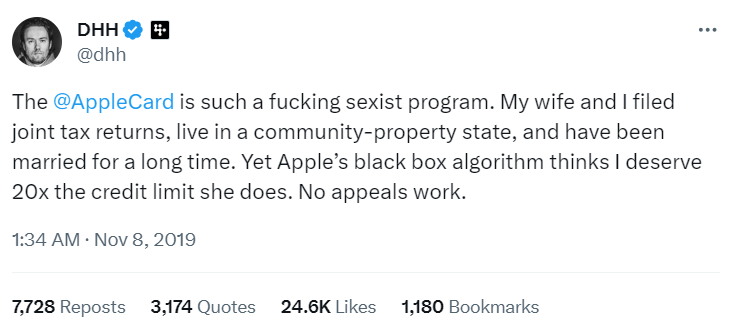

Similarly, Apple’s credit card which utilizes AI algorithms to determine creditworthiness was bashed for discriminating against women on the accusation that it offered smaller limits of credit to women as compared to their male counterparts. The issue came into the limelight in 2019 when an influencer took to his X (formerly Twitter) that Apple Credit Card had portrayed sexism.

As per him, his credit line was 20x more than his wife’s despite both of them sharing the same income and credit score. The perplexing aspect of this accusation was that the software did not solicit any gender input. The discrimination it exhibited, occurred without any awareness of gender per se, which highlights AI’s potential to amplify gender-based bias.

Gym Software

Computer software being used by a gym in the UK automatically categorized Dr. Louise Shelby, a woman, as a male after she had entered “doctor” as her title. Having categorized her as a male, she was given access to the men’s changing room. She was told that if she needed it fixed, she should remove her professional title from the gym’s online registration system. These instances highlight AI’s potential to exacerbate systemic bias held against women, undoing decades of progress in women’s rights.

Furthermore, such instances contravene anti-discrimination laws, in particular, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW). CEDAW defines “discrimination” as, “any distinction, exclusion or restriction made on the basis of sex which has the effect or purpose of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by women, irrespective of their marital status, on a basis of equality of men and women, of human rights and fundamental freedoms in the political, economic, social, cultural, civil or any other field”.

This definition indicates that when AI systems exhibit such bias against women, they essentially perpetuate discrimination and reinforce societal inequalities. Without a robust legal framework governing the intersection of innovation, ethics, and law, and providing mechanisms to mitigate these AI deficiencies, safeguarding fundamental rights, especially of women, becomes a daunting endeavor.

Privacy & Data Protection

Without the data provided to it, AI is an empty vessel, and this reality underscores the growing apprehension surrounding the impact of AI technologies on data privacy. One’s facial features or voice can be misused by ‘bad’ actors to create AI-generated fake images or videos, mostly of women (often sexual in nature) to injure their social repute, take revenge, show ‘masculinity’, ‘sextort’, bully, or spread misinformation.

Such fake images and videos, which are referred to as ‘deepfakes’ are predominantly non-consensual creations, which, in particular, target women. As per the report of Sensity AI, out of the non-consensual sexual deepfakes, 99 percent were made of women. Individuals, including women, who have dared to advocate against such image-based sexual abuse, have experienced becoming targets of such abuse themselves.

There are concerns that the creation of deepfakes does not amount to the processing of ‘personal data’ of individuals and thus does not infringe the data or privacy rights of individuals. Some argue that the data protection rules do not encompass the governance of deepfakes, as the content produced through deepfake AI technologies does not belong to any real individual. Chidera Okolie contends that while this assertion may hold in cases involving deepfakes of non-existent or fictional individuals, it becomes less defensible when applied to deepfakes of real, existing individuals.

Okolie maintains that when a deepfake is created by using the data of an individual, and the end product i.e. the deepfake can be traced back to that person, it would fall under Article 4(1) of the EU General Data Protection Regulation: Regulation (EU) 2016/679, the definition of ‘personal data’, which is defined as, “any information which are related to an identified or identifiable natural person.” Therefore, a deepfake that can be linked to an individual could be considered the ‘personal data’ of that person—a non-consensual deepfake thus violates an individual’s data and privacy rights.

The creation and dissemination of non-consensual sexual deepfakes featuring women can subject women to severe psychological trauma. In theory at the very least, there is a striking parallel between viewing one’s pornographic deepfakes and being drugged and violated. This underpins AI’s capability of perpetuating gender-based violence against women, becoming the modern mode of stripping women of their sexual autonomy.

Apart from the mental trauma on the victim, the effects of sexual deepfakes targeting women are particularly dangerous in developing Southeast Asian countries, such as Pakistan, where killing women in the name of ‘honor’ is still endemic. Although the country’s legal framework forbids honor crimes, prevalent cultural stereotypes often rationalize such mindless acts, even resulting in the exoneration of individuals accused of murder under the guise of honor.

The far-reaching consequences stemming from violations of personal data and the abuse of generative AI to produce explicit deepfakes emphasize the need for comprehensive regulation of AI on the issue. Non-consensual explicit deepfakes of women run counter to international legal instruments such as the CEDAW and the Lanzarote Convention.

On a national level, different countries have different legal frameworks governing the issue; most of them bring explicit deepfakes within the ambit of criminal law as sexual offenses. The UK’s Revenge Pornography Guideline, Nigeria’s Sexual Offenses Act 2003 and Violence Against Persons (Prohibition) Act 2015, Pakistan’s Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act (PECA) 2016 and Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) 1860, and Canada’s Canadian Criminal Code, all outlaw sexual exploitation of women, potentially encompassing instances of non-consensual explicit deepfakes targeting women.

Technology & Women at Work

The quantitative and qualitative impacts of technological change also disproportionately affect women. Women currently occupy a significant portion of low-skilled and labor-intensive jobs, positions that teeter at the edge of displacement due to advancements in automation and technology. It is estimated by McKinsey and Company that around 15% of the global workforce could be displaced between 2016 and 2030.

The International Labor Organization’s report titled ‘The Game Changers: Women and the Future of Work in Asia and the Pacific’ has highlighted how technology is going to affect the garment sector in APAC countries—a sector dominated by working women in the region. For women coming from Southeast Asian countries with conservative social norms such as India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, the garment sector has played a pivotal role in enhancing their economic and social positions. The technological displacement of this sector would therefore deliver a severe blow to the economic and social rights of women in the region.

With the phasing out of low-skilled and labor-intensive jobs, new opportunities may emerge for women in job markets traditionally dominated by men. However, technology cannot bridge gender inequality automatically—“it largely depends on the design of the technology and the capabilities of women from under-represented groups to access and use technologies and solutions that respond to their needs.”

While women possess the capability to excel in tasks traditionally performed by men, the decisive factor in their shift from low-skilled positions to roles once monopolized by men hinges on deeply ingrained societal prejudices and attitudes. Nevertheless, online work procurement through app-based platforms has opened gateways for women to access jobs in male-dominated fields.

The flexibility associated with such procurement of work is a way to open new job opportunities to women; however, research by Barzilay and Ben David shows that there are significant pay gaps between male and female online workers. Furthermore, the pace of digitization has left labor laws lagging significantly behind the evolving labor landscape, posing potential harm to women’s economic and social rights. Conversely, women might find increased opportunities for employment in the technology sector itself, encompassing the fields of automation, robotics, and artificial intelligence, taking on roles such as technicians, clerical, or administrative support staff.

In the Philippines, women already constitute 59% of the business processing outsourcing workforce. To sustain and extend this trend across the APAC, it is crucial to offer necessary training and support to women in the region. Additionally, certain companies, such as All Claims Adjustment Bureau, hire female workers from the APAC region for remote positions. Although the primary motivation behind such endeavors may be cost-effectiveness, these opportunities nonetheless stand as crucial pillars in protecting the employment rights of women in the Asia Pacific in the face of the changing technological landscape.

Conclusion

As the human race enters into the epoch of the 4th industrial revolution, there are legitimate concerns regarding the adverse impacts of this technological age on women and their rights. This concern is grounded in the manifestations of AI discrimination, violations of women’s data privacy rights, and the imminent peril of their job displacement to technology and automation.

The unprecedented rate of technological advancement underscores the need for regulation of AI and other emerging technologies. Such regulation should aim at adopting a human-rights (or perhaps women-rights) approach—testing and validating AI softwares along the lines of established women-rights norms and standards. It also warrants the upgradation of the existing legal framework for the protection of women’s rights to keep them relevant in the contemporary age.

Regarding the looming threat of job displacement of women, states should introduce measures to support women in preparing and adapting to the morphing tech landscape by investing in the development of their skills through training.

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please check the Submissions page.

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.