In “The Silmarillion,” Tolkien explained the origins of orcs. Orcs had originated from the mighty and learned elves. The dark lord, Melkor, had captured many elves, tortured them, and warped them into his servants who served him in fear. These products of tyranny and torture became known as Orcs, who fought as soldiers of evil for millennia and ensured that the tyranny’s positive feedback cycle continued.

One of the things that makes Tolkien such a legendary writer is that his fiction provides deep insights into our realities. The mechanism of the creation of orcs correctly explains how tyrannies warp and destroy nations by instigating self-propelling positive feedback cycles. For example, British colonialism destroyed the society of the regions comprising Pakistan today and created a captive/slave local elite that would serve the British tyranny in the same way orcs served Dark Lord Melkor. That elite continued its orcish ways even after the British left and found new neocolonial masters in the Americans, just like orcs became enthralled by Sauron after the fall of Melkor.

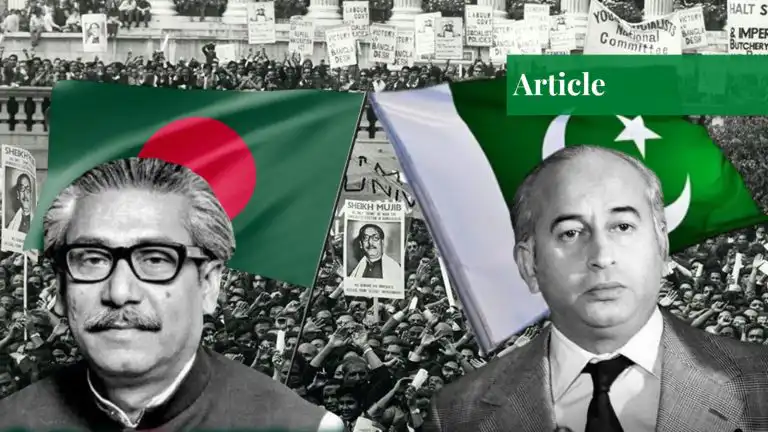

The Fracturing of a Union

The traumatic birth of Bangladesh in 1971 and the tyranny that preceded its birth created a similar mechanism. To understand this mechanism, we must understand the tyranny that warped Bangladesh (then East Pakistan). The Bengalis of East Pakistan had been the most enthusiastic patriots initially. However, Ayub Khan’s martial law of 1958, which led to complete West Pakistani hegemony (the Pak Army was 95% West Pakistani), alienated many of them due to non-representation. A narrative took root that East Pakistan was being ruled as a colony by West Pakistan.

At that time, the Awami League was the largest East Pakistani political party, and it was led by H. S. Suhrawardy. Suhrawardy was considered one of the founding fathers of Pakistan by many. He had served as the prime minister from 1956-57, and his era is remembered today as the time in which the gulf between East and West Pakistan was at its narrowest. Suhrawardy believed in the integrity of Pakistan and had effectively curbed many hotheads in his party, like Sheikh Mujib, who had started thinking about secession during the 1950s. However, Suhrawardy was jailed by Ayub Khan and was released in poor health later on.

His death in 1963 (there were unsubstantiated but widely believed rumors that he had been poisoned) and the infamous rigged election of 1965 (in which almost all of East Pakistan backed Fatima Jinnah) strengthened the separatist tendencies among East Pakistanis and brought Sheikh Mujib to the fore. Sheikh Mujib’s rhetoric was simple: The West Pakistani army has no sense of fair play, and the tyranny cannot be overthrown through any legal means, like elections, etc. Mujib also strove to enlist Indian help in his quest for separatism and power. Unlike Suhrawardy, he was a man with no scruples, morals, or even an ideology. His political strategy was solely based on spreading hatred against West Pakistan. As I have explained in a previous article, Sheikh Mujib’s brand of hate politics and the military regime’s tyranny developed a synergy and fed off each other.

The 1971 Cataclysm: Civil War and the Dilemma of Loyalty

After Pakistan’s military dictator Yahya Khan (who had kicked Ayub aside in 1969) denied Sheikh Mujib the opportunity to assume the office of the Prime Minister of Pakistan despite the victory of the Awami League in the 1970 elections, East Pakistan descended into violence and anarchy on the 1st of March, 1971. The Awami League now openly talked about creating a sovereign Bangladesh and would only go as far as to consider a merely symbolic confederal arrangement between West Pakistan and Bangladesh. Goons related to the Awami League (allegedly armed by India) committed horrific acts of ethnic violence against non-Bengalis.

Yahya Khan showed little interest in curbing this violence and appeared solely concerned with perpetuating his rule over Pakistan. When it became clear to him that the Awami League had no intention of accepting this, he chose to launch a military operation against it on the 25th of March, 1971. Thus began the bitter civil war that tore Pakistan asunder, resulting in thousands of killings, and gave India “the opportunity of a century” to strike forceful blows against both wings of Pakistan and cement its influence in the soon-to-be-born state of Bangladesh.

The 1971 war (known as the Liberation War in Bangladesh) sandwiched the people of Bangladesh between two tyrannies. On one hand was the vicious and illegitimate military dictator of a “hard state” who had no compunctions in committing horrific and widespread atrocities against his countrymen. On the other hand was a separatist party led by an opportunist, which became totally dependent on Indian support following the military crackdown. Many Bengalis who supported the latter did so not because of love for the Awami League but only to free their country from the tyranny imposed by a vicious military dictator.

Quite a few of the Bangladeshis who fought against Pakistan were wary of Indian intentions and loathed its total control over the Awami League’s residual leadership (Sheikh Mujib himself remained in a Pakistani jail throughout the whole war, which spanned 8 months). Military commanders like Ziaur Rahman and Shariful Haq Dalim were quite vocal in their belief that Bangladesh wanted freedom instead of replacing Yahya Khan’s tyranny with Indira Gandhi’s!

The same was the case for those Bengalis who fought on the side of Pakistan. Many of them loathed Yahya Khan and his dictatorship. However, they believed that the defeat of the Pakistan Army in East Pakistan would lead to Bangladesh’s birth as a satellite state of “Hindu” India. The most important East Pakistani organization that held this view was the Jamaat-e-Islami (JI). JI had been a party that had stood up bravely against Ayub Khan’s dictatorship under the leadership of Maulana Maududi.

It had claimed (plausibly) that the elections of 1970 had been heavily rigged by the Awami League goons with passive support from Yahya Khan’s military that stood aside and enabled the Awami League to bully all the other political parties before and during the elections. The volunteers who fought on Pakistan’s side were mostly linked to JI and chose the name “Al Badr” for their paramilitary organization. They widely became known as “razakar” (an Urdu word that means volunteer) among the Bangladeshi people. Wars are a cruel business. One of the worst fates that can befall a human is to be stranded on the losing side after a war. This is what happened to the JI, which was labeled as a traitor organization in independent Bangladesh following the surrender of the Pakistan Army.

Swapping One Despot for Another

As a parting gift of a departing tyranny, Yahya Khan’s army had asked for no safeguards for the local Pakistani loyalists when it suddenly surrendered to India on the 16th of December, 1971. It had not even bothered to inform them of the impending surrender. Cast adrift, they were left to be butchered by the victorious Awami League. The word “razakar” became a synonym for traitor/collaborator in independent Bangladesh.

It wasn’t long before the Bangladeshi people realized that they had swapped Yahya Khan’s tyranny for the twin tyranny of India and the Awami League. The latter found it convenient to label all its political opponents as “razakars” as Sheikh Mujib strove to emulate Yahya Khan in trampling the people of Bangladesh. Just as Yahya had (ab)used the Pakistan Army as an instrument of state repression, Mujib created his own army known as the Rakhi Bahini, which committed widespread killings and torture to force the people of Bangladesh into submission. Sheikh Mujib himself had been a product of the tyranny of Ayub and Yahya Khan. That tyranny had warped and mangled the societal dynamics in East Pakistan/Bangladesh and created a fascist political organization that abused Bengali nationalism in a way similar to how Islam had been abused to hoodwink the people by the Pakistani military dictatorships.

Mujib was killed in 1975 by some of those very men who had fought against Pakistan in the 1971 war. By then, he had become one of the most hated men in Bangladesh due to his corruption, vicious repression of political opponents, and complete subservience to Indian hegemony. This created a golden opportunity for Bangladesh to finally gain complete freedom from tyranny. Alas! It was not to be. Those who followed Mujib proved themselves little better. The rule of law remained sporadic at best, and corruption remained rampant. However, General Ziaur Rahman (the man who belatedly replaced Mujib as the nation’s leader) understood the importance of resisting Indian hegemony. Unfortunately, the Indians had made some very deep investments in Bangladesh, and they enjoyed the loyalty of a significant chunk of Bangladeshis on account of religious ties.

The JI orchestrated a cautious resurgence during the Zia era. Zia wanted to counter the Awami League through JI. He also understood the political value of Islam in a country like Bangladesh (90% of whose people are passionate and practicing Muslims) and wanted to reintroduce this element in Bangladesh’s politics to strengthen his position against the avowedly secular Awami League. JI’s position of junior partner to Zia’s Bangladesh National Party (BNP) provided it with precious breathing space.

Unlike the JI in West Pakistan, the Bangladeshi JI proved very successful in creating and running social organizations for the health, education, and welfare of the Bangladeshi people. It accrued significant soft power through these organizations. JI also established a stellar reputation for honesty, as it was deemed the least corrupt political party in Bangladesh by a distance. However, it could never compete with the BNP and Awami League due to one major issue: the label of “razakar,” the gift that Yahya Khan’s tyranny had bequeathed to it!

The Second Revolution: The 2024 Uprising and the Ghosts of History

2024 proved an epochal year in the history of Bangladesh. After 15 years of Sheikh Mujib’s daughter, Sheikh Hasina’s tyrannical rule (made possible through Indian help), the Bangladeshi people had had enough. They rose up in an impressive revolution and even chanted slogans like “I am a Razakar” in defiance of Hasina’s dictatorship. The invocation of the word “razakar” shouldn’t delude anyone into thinking that this uprising was meant to undo 1971 or that the protestors were eulogizing the actual razakars of 1971.

It was just a political expression directed at negating Hasina’s ploy of labeling every political opponent as a “razakar.” In fact, many revolutionaries who took to the streets in 2024 envisioned themselves as taking part in a second revolution (after the first one in 1971) that would complete the quest for freedom and justice for Bangladesh. They didn’t despise Hasina and her father, Sheikh Mujib, for the secession of 1971 (many Bangladeshis consider this the only redeeming quality of Sheikh Mujib). They despised them for trying to make Bangladesh a slave state to India, for their mind-blowing corruption, and for their vicious atrocities committed against the people of Bangladesh after mislabeling them as traitors/razakars.

The 2nd revolution of Bangladesh did vindicate JI’s long-held stance about India, though. If the revolution of 1971 was aimed towards obtaining freedom from what was termed by Bangladeshis as the Pakistani tyranny, the revolution of 2024 was squarely aimed towards thwarting Indian hegemony. Sheikh Hasina’s vicious crackdown only fanned the flames of the revolution further. Like in 1971, the students formed the vanguard of the uprising, but this time their chief ally was the JI.

The soft power of JI, the sacrifices it gave during the long night of Hasina’s tyranny, and its capacity to outsource its welfare organizations in the service of the revolution cemented its role as one of the two prime movers behind the 2nd revolution. The BNP, in contrast, was a fringe player in the revolution. It was also repressed mercilessly by Sheikh Hasina, but it suffered much less than the JI. It didn’t have the vibrant energy of the students or the welfare muscle of the JI.

When the revolution succeeded in toppling Sheikh Hasina, the role of BNP underwent a tremendous shift. Unlike the students and JI, the BNP was similar to the Awami League in being a traditional political party whose chief strength didn’t lie in ideology or providing services to the people. It lay in widespread patronage networks. The fall of the Awami League enabled the BNP to take over its patronage networks as well. It made sense for the BNP to stall the revolution and enable the revival of “traditional politics” to counter the momentum of the youth who were clamoring for big structural changes with far-reaching consequences. The JI, on the other hand, found itself mostly in sync with the students in demanding a complete overhaul of the Bangladeshi state. So, the student revolutionaries’ National Citizen Party (NCP) and the JI formed an electoral alliance against the BNP in a two-horse race for the momentous 2026 elections in Bangladesh.

An interesting fact about this election is that the BNP favored the traditional first-past-the-post system while both the NCP and JI favored a proportional representation system. The former is much more suited to patronage politics because in it, every vote doesn’t count, and full representation from a constituency can be won by getting only 30-40% of the total votes. In short, most of the voters remain unrepresented in such a system. On the other hand, every vote is deemed worthy of representation in the parliament in the proportional system.

The NCP and JI knew that they faced an uphill battle against patronage politics, a battle they had to win in order to complete the revolution. The JI was the major partner in this alliance, as it was a very experienced and well-organized political party. Tellingly, it was the debt of history and the price of tyranny that ended up thwarting the JI. The effects of tyrannies linger long even after their eradication. Unfortunately for Bangladesh, the first tyranny brought over that land by a drunk (on both power and alcohol) Pakistani general and his henchmen, and the second tyranny that spawned from the loins of the first in the form of Sheikh Mujib’s kleptocratic, violent, and fascistic despotism, combined in birthing ghosts that halted the progress of Bangladesh’s 2nd revolution.

The label of “collaborator” was engraved upon the JI due to Yahya’s tyranny, and the remnants of the Awami League combined to ensure a resounding victory for the BNP! The latter factor’s importance can be judged by the fact that pre-poll surveys had shown JI and BNP neck and neck at around 32-35%. JI ended up getting around 32% of the votes in the elections, but the BNP ended up getting around 50%!

The key moral of the story of Bangladesh’s 2nd revolution is that tyranny/imposed slavery warps and wrecks the nations through positive feedback mechanisms whose impact lingers on even long after the tyranny is gone. The ghosts of Yahya Khan and Sheikh Mujib, though weakened, haven’t vanished completely yet. It was these ghosts whose shadowy arms snatched away a golden chance of completing the revolution in Bangladesh. I hope that the JI and NCP continue guarding and nurturing their revolution until the time comes when the ghosts of tyrannies are finally vanquished with the birth of a Bangladesh that would possess the potential to become a very prosperous country, with the potential to thwart the encroaching Hindutva-crazed India decisively and play a leadership role in the Islamic world.

The Pakistani Parallel: A Nation Still Caught in the Feedback Loop

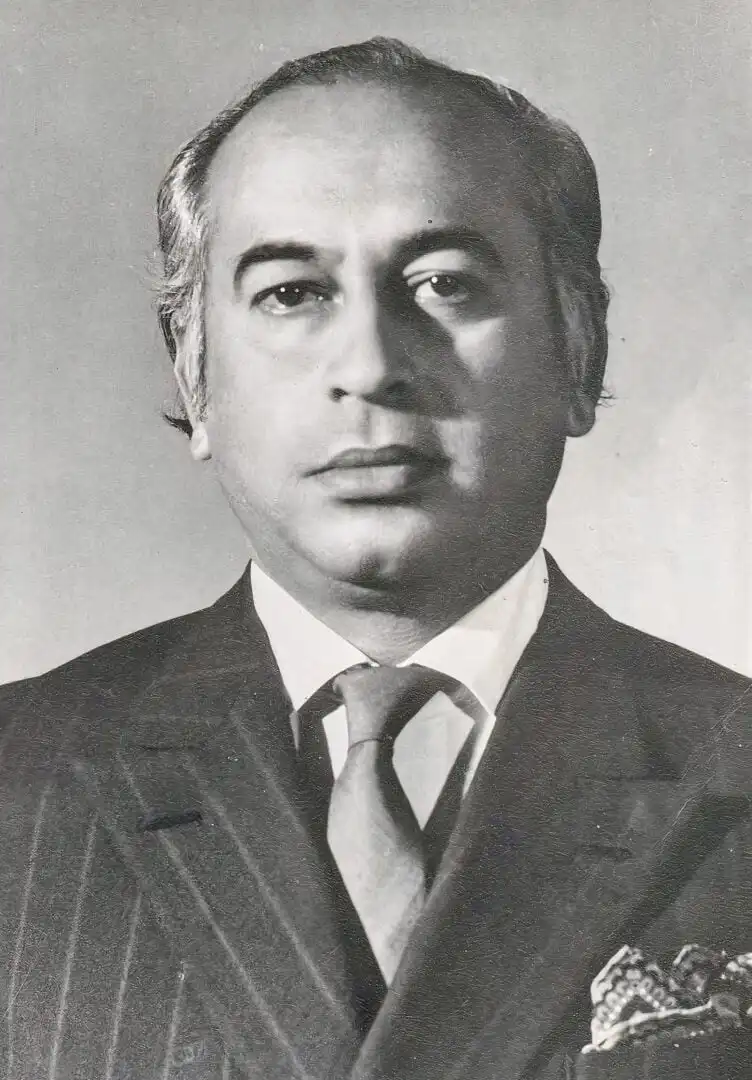

In the end, I would discuss my own country, Pakistan, a little. Unlike Bangladesh, the ghosts of past tyrannies haven’t faded at all. In contrast, they have solidified into huge monsters carrying on the legacy of tyrants like Yahya Khan and charlatans like Mr. Bhutto. We must remember that it was Mr. Bhutto who was the chief enabler of Yahya Khan’s tyranny. He thought that he could win power by egging on Yahya to eliminate Mujib. The shrewd Bhutto knew quite well that he had no democratic mandate, and his only hope for power lay through intrigues and fomenting chaos. He hoped for a destructive civil war that would destroy both of his chief rivals (the Awami League and the Pakistan Army).

He got what he wanted, and the price of his ambition was paid through a horrible civil war that brought ruin to East Pakistan/Bangladesh and enduring shame and humiliation to the rump that remained. Today, Mr. Bhutto’s son-in-law reigns as the president of Pakistan on the basis of an election in which the public mandate was brazenly desecrated and stolen by the successors of Yahya Khan. We must remember that it would take decades, if not centuries, to undo the effects of the cycles of tyrannies engulfing Pakistan.

Just like Yahya Khan in 1971, the present regime is pushing Pakistan to the brink of another civil war in futile attempts to entrench itself by trampling the people and soliciting the Western masters in order to gain their blessings and support. While India was the chief puppeteer behind Bangladesh’s tyrants and kleptocrats after 1971, it was always the West (chiefly the USA) that held the strings of both military and civilian Pakistani tyrant-puppets in its hands.

I will end this article by sharing the advice of the renowned Pakistani academic Professor Shahid Alam to our nation:

“Pakistanis alone can end their humiliation: only they can overthrow the system that has castrated them for more than six decades. Pakistan was born gagged and bound, delivered into the control of the very classes that had been the chief collaborators and chief beneficiaries of colonial rule. These neocolonial hirelings have served themselves and their Western masters quite well. Between themselves, the two local contracting parties of the neocolonial enterprise—the military and the party of the landlords—have taken turns running the country into the ground. When the people have appeared to get sick of one of these parties, it has transferred power to its twin, which offers itself as just the medicine that will cure the country’s sickness…More than at any other time, growing numbers of Pakistanis have been grooming themselves for service to the Empire that rules from Washington, as their predecessors once eagerly sought to serve the British Raj. This groveling by Pakistan’s elites will only change when the people act to change the incentives on offer to these soulless servants of Empire. But this will only happen when the people of Pakistan can put these mercenaries in the dock, charge them for their crimes against the people and the state, and force them to disgorge the loot they have stowed away in Western banks.”

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please visit the Submissions page.

To stay updated with the latest jobs, CSS news, internships, scholarships, and current affairs articles, join our Community Forum!

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.

Dr Hassaan Bokhari is a graduate of Rawalpindi Medical College, Rawalpindi. In 2018-19, he cleared the CSS exam and was 34th in Pakistan. However, he declined to join the civil service in order to pursue his passion for the study and analysis of history more freely. Presently, he is running a YouTube channel "Tareekh aur Tajziya (History and Analysis)" which focuses on the objective analysis of history and current affairs. Dr. Hassaan Bokhari has authored a book titled "Forks in the Road" about the 1971 fratricide and has also headed the India Desk at South Asia Times Islamabad. He aims to play a part in the process of enabling the nation to understand its history in a perspective marked by objectivity, honesty, and confidence.