Abstract

This paper aims to discover the underlying efforts of regional states to bring peace and stability to Afghanistan. For that purpose, the interests of regional states in Afghanistan are briefly mentioned in the paper, making the base for the research question. The paper’s main focus is on why the regional states want a peaceful Afghanistan and how they tried, in their respective capacity, to stabilize the region.

Afghanistan seems more like a playground rather than a graveyard for empires and regional contestants. These states tried to establish a peaceful Afghanistan via military approaches, geopolitical interactions, economic investment, cozying up with Afghanistan’s and their own internal dynamics. Whether these states were successful or not in their efforts is a separate debate, but the underpinning importance of a peaceful Afghanistan has pushed states towards these efforts. Drawing from the empirical data provided, one can conclude that each state was worried about its interests, survival, security maximization, and relative gain.

Keywords: Afghanistan, Peace, Stability, Pakistan, Iran, China, Central Asia, Regional Efforts.

Introduction

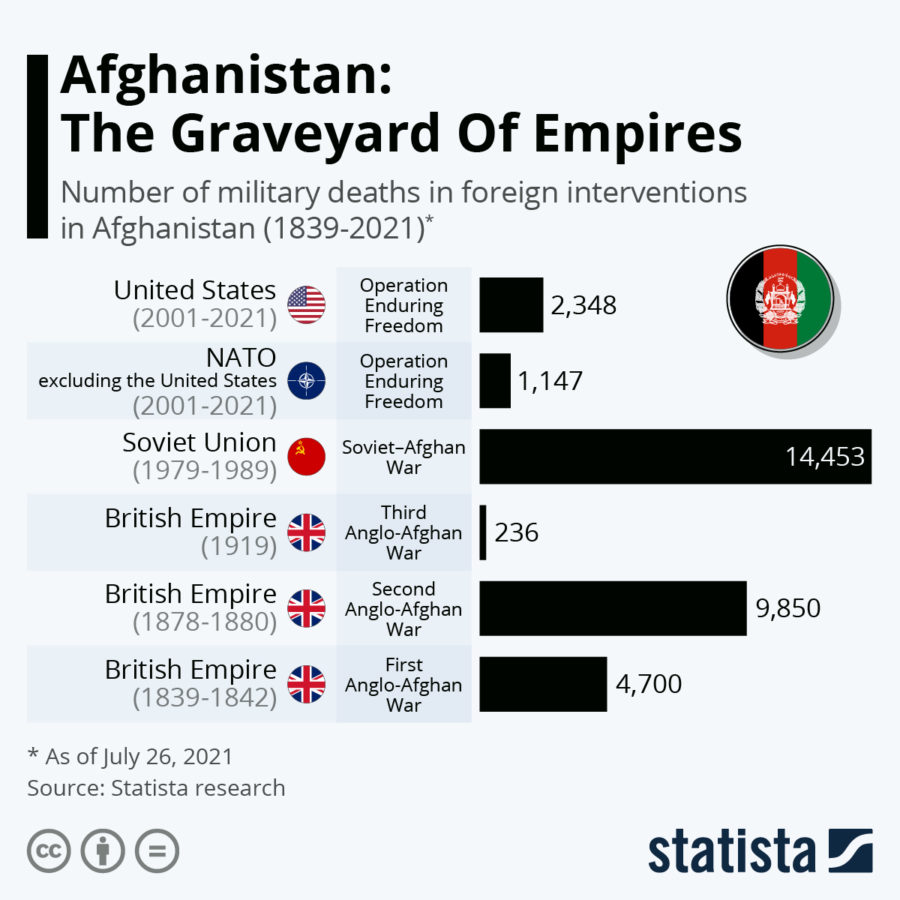

Since the 1970s, Afghanistan has been politically unstable due to the interference of global and regional powers along with multiple actors striving for power. The aphorism the “graveyard of empires” aged well. However, it might be argued that Afghanistan is “the playground of empires”.1

Over the years, the country has passed through terrorism, drug trafficking, human rights abuse, political turmoil, geostrategic and geo-economic tussle, and societal deterioration. Amidst all this chaos, regional states, especially Afghanistan’s neighbors, tried hard to bring peace and stability to the unfortunate land. The countries that played a significant or geostrategic role in establishing a peaceful Afghanistan are Pakistan, China, Iran, and the Central Asian Republics.

After the Kabul fall last year, Islamabad arranged a virtual meeting of the foreign ministers of regional states to discuss the rapidly changing political situation in Afghanistan.2 The topic under discussion was peace and reconciliation in Afghanistan. Everyone agreed that there is no military solution for creating a peaceful and stable Afghanistan. However, this meeting revealed the interests of the regional states in Afghanistan.

Islamabad’s primary concern was the growing Indian presence, especially in the border areas. It is not in the interests of Pakistan to have a confrontation on both sides of its border. Beijing was concerned about terrorism. China feared that non-state actors (like the East Turkestan Islamic Movement) would damage the Chinese assets in the region. China wanted a friendly relationship with the Afghan administration. Whereas, Turkey’s interest lies in wanting a big say in the Islamic world, for which it saw an opportunity in Afghanistan, and offered security.

Iran and Afghanistan have a common enemy named the Islamic State – Khorasan Province (ISKP), so, Iran wanted a bold action against the group. The Central Asian Republics (CARs) also have apprehensions about the growing ISKP presence in the region and fear that Afghanistan would become a haven for them.3

Apart from that, the Central Asian Republics always wanted to protect the social, political, and economic rights of their respective minorities in Afghanistan. Moreover, these states saw an economic opportunity in Afghanistan and want to export their energy resources through Iran or Pakistan, for which stability in Afghanistan is vital.

Research Problem

All the neighboring states want a peaceful and stable Afghanistan to obtain their respective interests. Their fates, more or less, are connected to that of Afghanistan. Thus, the following study will answer the research question: Why are regional efforts significant for Afghanistan’s peace and stability?

This research question has been explored by answering the following sub-questions:

- Were these efforts based on self-interest or was it the liberal paradigm that pushed the states to bring peace to Afghanistan?

- How did the geopolitical compulsions of the regional states push them in making efforts for the stability of Afghanistan?

Theoretical Framework

To answer our research question, we’ve used the realist framework. Realists say that the state is a main and unitary actor in international relations. They do not exclude other bodies out of the system rather narrate that their role is limited. According to the realists, national interest is the guide that leads a state to speak and act in one way. States are considered as rational actors; thus, their rational choice is the pursuit of national interest.

States won’t take any steps that weaken their position in international politics. The competitive international system presses the leaders to ensure their states’ survival. States believe in the concept that there is “no guardian of the international system, and the structure is anarchic.” Another tenet of realism is “self-help”, which underpins the idea that there is no permanent friend or permanent enemy, the only thing which is permanent is interests.

According to the realist thought, states are after survival, power maximization, relative gain, and national interests. In the context of Afghanistan, the regional states want to pursue their interests, and their interests lie in the stability of Afghanistan. Without a peaceful Afghanistan, other states won’t be able to experience peace, stability, and prosperity in their own country.

Regional States & a Peaceful Afghanistan

1. Pakistan

In 2011, while signing a new partnership deal with India, former Afghan president, Hamid Karzai, remarked that India was Afghanistan’s friend, but Pakistan was its twin brother.4 We are conjoined twins and whether we accept it or not, we can’t change geography. Pakistan shares its longest border with Afghanistan, which is 2,670 km.

The trouble in Afghanistan directly disturbs Pakistan’s security and economy, which is why it continues to remain an essential stakeholder in Afghanistan. Pakistan views its security concerns in Afghanistan through the prism of India.5 Pakistan sees an opportunity in Afghanistan in strategic depth to overcome its geographical shortcoming.

Role in Establishing a Peaceful Afghanistan

From the beginning of the foreign invasion, Pakistan advocated a peaceful Afghanistan through talks and dialogue. In the 2001 Bonn Conference, when a roadmap for post-invasion Afghanistan was being drawn, Pakistan urged to invite the Taliban, assessing them as a major stakeholder in the war-torn country. Later in September 2021, in one of his op-eds, Henry Kissinger said that creative diplomacy could have prevented terrorism.6

After the troop surge in 2009, the Obama administration felt the reality on their throats and started talking about diplomatic engagements with the Taliban. However, throughout the last two decades, Pakistan maintained its stance on peace talks and thus, appreciated the High Peace Council established under the Afghan government in 2010. But its activities halted due to the assassination of Burhanuddin Rabbani.

With the Central Asian Republics and other key regional players, Pakistan mandated political, economic, counterterrorism, peace, and stability as crucial variables of cooperation in the heart of the Asia-Istanbul Process initiated in November 2011. Continuing the legacy, Pakistan initiated Murree Peace Dialogue in 2015, but it got sabotaged by the news of Mullah Omar’s death in the same year.7

In January 2016, Pakistan came up with the Quadrilateral Coordination Group (QCG). But it had one flaw and faced one setback. The flaw was the absence of the Taliban, while the setback was the death of Mullah Mansur in a US drone attack. Debacles of the past led to the Six Nations Talks convened in 2016. The talks included Russia, China, Pakistan, Iran, Afghanistan, and India.

The purpose was to encourage the Taliban to honor the peace process with the Afghan regime. But India hesitated from engaging with the Taliban and had reservations regarding China, Pakistan, and Russia that these states wanted to use the Taliban against the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS). Pakistan, Russia, and China, worried about the looming threat of ISIS presence in Afghanistan, formed a trilateral talks forum in late 2016. But this initiative didn’t get an endorsement from the US and European states, and Afghanistan was also concerned about its exclusion from the talks.

Pakistan has continuously been extending its political and diplomatic support to peace processes meant to bring stability to Afghanistan. The same was when Ashraf Ghani’s Afghanistan inked a peace deal with Hizb-e-Islami Gulbadin (HIG) in September 2016.8 This support has also been reflected in the highest military ranks of the Pakistan Army.

For example, in April 2018, during his visit to Moscow, General Qamar Javed Bajwa emphasized the importance of a peaceful and secure Afghanistan. The same stance was reiterated in June 2018, when General Bajwa traveled to Kabul. Pakistan also played a vital role in the Doha Peace Talks between the US and the Taliban. Due to the tremendous efforts of Pakistan for establishing a peaceful Afghanistan, a deal was signed by the Taliban and the US representatives on 29th February 2020, enacting the plan for the US troops’ withdrawal from the state.9 The Doha deal was a diplomatic win for Pakistan.

Development, Assistance, and Reconstruction

Besides diplomatic maneuvers and economic assistance, cultural exchange, education, and reconstruction are essential for building peace and stability. Pakistan has never been economically viable to support other countries via large-scale projects and economic assistance. However, since 2001, Pakistan has been providing financial, technical, and institutional aid and assistance to Afghanistan for its rehabilitation, reconstruction, development, and improving the capacity of state institutions, in hopes of making it peaceful and stable.

Under the Planning Commission of Pakistan, the state authorities established an Afghanistan planning cell destined to assist and evaluate projects designed for Afghanistan. In 2002, the government of Pakistan announced $100 million developmental aid for the rehabilitation and renovation of Afghanistan in the International Conference on Reconstruction Assistance to Afghanistan, held in Tokyo, to help the state facing violence and destruction for a long time.10

Pakistan financed many projects of Afghanistan, including the railway line from Chaman to Kandahar, reconstruction of the Torkham to Jalalabad Road, the road from Ghulam Khan to Khost city of Afghanistan. For the energy sector, Pakistan developed the electricity transmission line to Khost.

Pakistan provided 200 trucks, 100 buses, 38 ambulances, and aid to Kabul University, reconstructed many schools, constructed a block for faculty in Balkh University, and constructed a kidney center in Jalalabad city. Pakistan has provided 6,000 fully-funded scholarships to the students of Afghanistan, in which 100 seats have been reserved for females annually.11 In 2018 alone, 750 Afghani students have been enrolled in different universities of Pakistan to pursue their education.

2. China

China shares a tiny part of its border (74 kilometers) with Afghanistan. However, Beijing has mainly three overlapping and complementary national interests to fulfill in the context of Afghanistan.

Investment Opportunities and BRI

Afghanistan is at the heart of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). China has aspired to connect India to Iran via energy corridors, railways, and other infrastructure projects. In 2016, former Chinese ambassador to Afghanistan, Yao Jing, stated that there’s no connectivity without Afghan connectivity.12

At the economic level, China is highly viable, capable, and insistent on investment in Afghanistan. However, it’s only possible when there are no security issues. Due to weakening security conditions, China has been hesitating to invest. The security threat is the sole reason keeping China away from engaging with Afghanistan on mega-scale economic projects.

Despite being shy of economic interventions, China did some noticeable development in Afghanistan. The Chinese built Kabul’s largest public-sector hospital (Jamhuriat Hospital). For the people of Afghanistan, China developed national vocational education and training centers. China adopted the policy of cultural and educational exchange.

It inaugurated the Chinese department in Kabul University and invested heavily in the university. But the negative side of the fact is that most of the development remained in Kabul or its peripheries. Due to security concerns, the rest of Afghanistan remained thirsty for foreign investment.

Threat of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement

Chinese relations with Afghanistan have been state-to-state and stable since 2001. China has acted as a mediator and has included Afghanistan in bilateral and multilateral engagements. It has done shuttle diplomacy between Kabul and Islamabad. China also helped Afghanistan train Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and cooperated to build a base in Badakhshan.

China fears Afghanistan becoming a haven for terror groups hampering Chinese interests at the security level. It fears that the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) may get a strong foothold in war-torn Afghanistan, affecting China’s security and territorial integrity. China has a clear interest in lending help to Afghanistan to overcome the terror threats of multiple groups, including the ETIM.

Both countries carried out several ministerial-level visits regarding the common interest. At the diplomatic level, China has done a remarkable job. China has problems with ETIM, and the Taliban had links with this movement. Yet, China didn’t pick sides and avoided making another unnecessary enemy.

There were five occasions from 2014 till 2019 when Chinese officials met with the Taliban representatives for bilateral talks on the Afghan peace process. In July 2021, Chinese officials met with the Taliban.13 The Chinese media intentionally publicized this event to propagate that China is ready to engage with Afghanistan after the foreign troops withdraw.

3. Iran

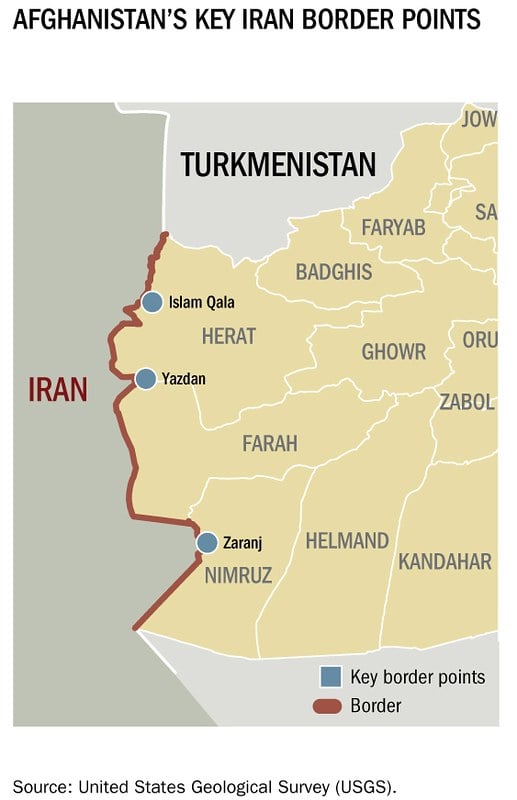

In 2001, Iran wanted an Afghanistan without the Taliban. Iran wanted to exterminate Salafi extremism from Afghanistan. In 1998, Iran was about to declare war on Afghanistan but it rattled to irregular means to obtain its objectives. It started supporting Tajik and Hazara militias along the northern border of Afghanistan. Iran’s Quds force and local Hazara militias carried out operations in the Herat province.14

However, in 2002, when Taliban were not there for some time and Karzai held the office, Iran drew four objectives – to cooperate with Karzai yet support its irregular allies, to reconstruct the areas that are strategic to Iran, to avoid direct collision with the US, and to reduce drug trafficking. Besides this, Iran had water flow and refugee issues with Afghanistan.

Iran’s Pragmatism

Iran had stored unofficial cultural ties with Afghanistan. Iran used its ties to exercise its influence, especially in Herat. However, Iranians also had contacts with non-Shia groups like Hekmatyar’s Hizb-e-Islami. Nevertheless, Iran was also in talks with Taliban representatives and hosted intra-Afghan talks. Iran has not allowed its religious groups to gain leverage on political forums. Iran never came to direct blows with the Taliban, but it was one of the prominent endorsers of the anti-Taliban movement along with Russia and India.

Politically speaking, Iran had leverage over the Northern Alliance, a Tajik resistance group. After the Taliban overthrow, when Karzai – a Pashtun – was pushed to lead the country, the Northern Alliance held resentment. It wanted to push for an administration with heavy Tajik influence and a non-Pashtun leader. Iran played a critical role to bring the Northern Alliance on board to accept Karzai.

James Dobbins, an American ambassador, commended the Iranian efforts.15 But the central government in Kabul didn’t allow Iran to exercise its strategic influence beyond the province of Herat. Iran was pragmatic, that’s why it heavily supported the US despite the mutual hostility between Tehran and Washington. However, the initial cooperation between the two in Afghanistan had distrust and tensions.

Iran had issues with the Taliban, but it did not aggravate the situation against its interest. It helped the Afghan insurgents militarily for two reasons. One, it wanted to pressurize the US in Afghanistan. Two, Iran had problems with the Baluch separatists and insurgents across the Iranian border with Afghanistan and Pakistan. Iran says that these insurgents are funded by the US, Israel, and Saudi Arabia. Thus, to neutralize this threat, Iran did not cut off its ties with the Taliban.

Increasing Influence Through Investments

Iran aims to create a sphere of economic influence and a transit hub for Central Asian trade. Iran pledged an amount of 500 million dollars for Afghanistan in 2002.16 Most of this aid went to infrastructure, education, and energy development. This pledge was the 12% of 4.5 billion dollars promised for Afghanistan at Tokyo’s International Pledging Conference (2002).17

At the London Conference in 2006, Iran pledged 100 million dollars more. Bilateral trade between the two countries stood at almost 5 billion dollars in 2013, increasing 250% compared to 2011. However, this trade volume was lopsided, favoring Iran. One of its reasons was Afghanistan’s weaker industrial base. Iran had used its economic advantage for political leverage.

Iran’s investment remained limited to the Herat province. To link Iran’s Dougharoun with Herat, it allocated 43 million dollars for paving a 125-kilometer long “Golden Transit Route”. Tajikistan obtained grants and loans from Iran to construct a 5-kilometer long Anzab tunnel, eventually connecting Iran with China via Herat, Mazar-i-Sharif, and Tajikistan.18 Iran built multiple schools in the province of Herat. Some of these schools even borrowed the Iranian curriculum and helped propagate the Iranian narrative.

Chabahar Port’s Significance

Iran’s Chabahar Port also had significant importance for Afghanistan. India urged to connect Afghanistan to the Indian Ocean via roads and railways through Iran. Chabahar is undoubtedly motivated by the geopolitics between China and India, and India wanted to cut off Pakistan to reach Afghanistan and build a stronger partnership.

Iran’s relations with India are also based on Iran not wanting to be isolated in the international system. On the one hand, if the Chabahar adventure succeeds, Afghanistan will be free of Pakistan’s influence, while on the other hand, Pakistan will lose a crucial amount of capital when the trade routes are changed.

Water Disputes, Drug Trafficking & Refugees

Iran is concerned about water disputes, narcotics, and Afghan refugees. The development projects in Helmand have exacerbated the water dispute. Iran is worried about the water flow due to dams built for supporting Afghan agriculture. Iran was accused of attempting to sabotage the dams under construction.

A captured Taliban commander claimed that Iran offered him 50,000 dollars to sabotage the Kamal Khan Dam in Nimroz. Iran is also worried about Harirud, which flows from Herat into Khorasan-e-Razavi. India has built the Salma Dam on Harirud, which would affect 3.4 million Iranians.19 Iran also protested over the construction of the Baksh Abad Dam in Farah.

Afghanistan is a source of Iran’s drug problems. The International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) failed to counter drug trafficking. Under the banner of the UN, Iran has housed the Joint Planning Cell with Afghanistan and Pakistan to share intelligence to eradicate smuggling and drug trafficking. But Kabul does not have enough capacity for border security.

The US has accused the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) of covering the drug traffickers. It seems ironic, but it might be true in a way that Iran used drug money to support its militias across Afghanistan.

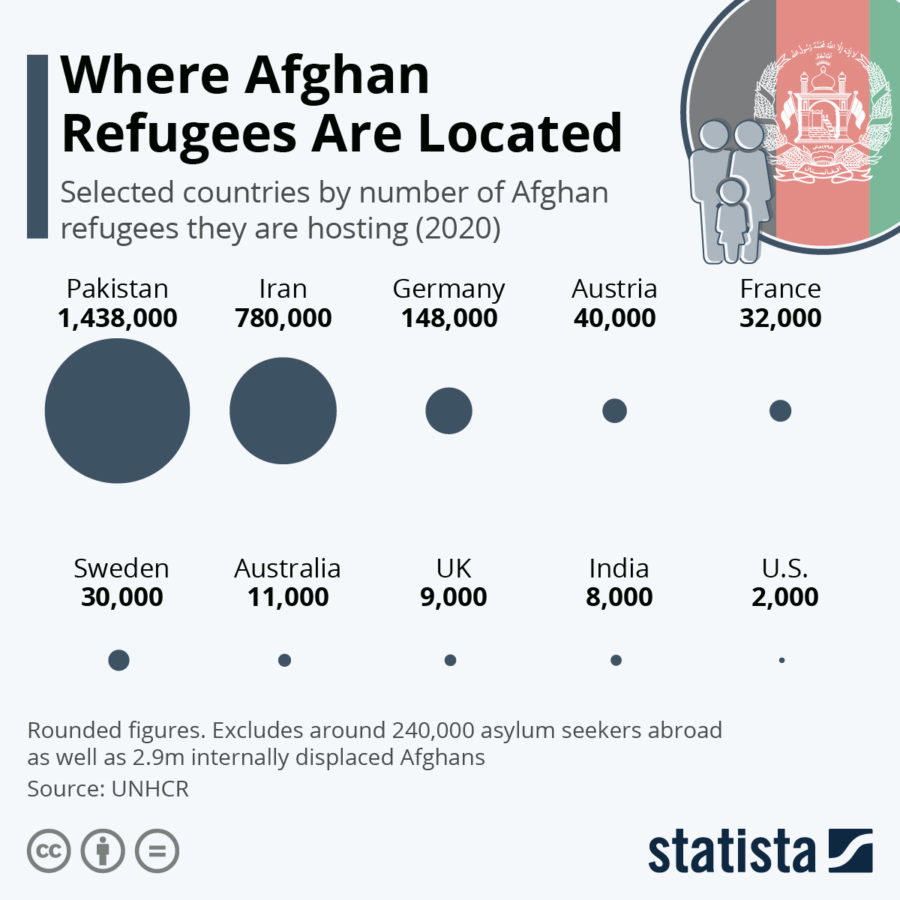

Iran has hosted approximately a million Afghan refugees. Iran took a hardline against undocumented refugees, and it deported more than 100,000 undocumented refugees. In 2012, Iran thought of repatriating the Afghan refugees by 2015. It warned that it would rapidly deport the refugees if Karzai signed a US defense pact.

4. Turkey

In the last two decades, Turkey faced two significant dilemmas. One was 9/11, while the other was the Arab Spring (2011). In the case of Afghanistan, Turkey’s soft power came into use, as mentioned by one of the former Turkish ambassadors. Behind every move of Turkey in Afghanistan, there were four motives.

Firstly, Ankara searched for a proactive foreign policy. Secondly, Turkey didn’t want Afghanistan to become a haven for extremism and terrorism. Thirdly, Turkey wanted to strengthen its ties with Afghanistan and Pakistan in economic and political terms. Lastly, Turkey was concerned about the Afghans. Turkey contributed militarily as well as non-militarily to obtain a peaceful Afghanistan.

Projecting a Positive Image of the Turks

Ankara was a part of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) coalition forces, yet the Afghans had a positive attitude towards Turkish forces, exploring the historical and cultural ties between the two nations. Turkish officials claimed to have won over the hearts of the Afghan people. Turkey’s main motto was “Afghanistan for Afghans”.20

In Afghanistan, the Turks channeled their military capabilities through the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), but they refrained from taking part in combat operations. Turkey is very cautious about the level of military involvement in Afghanistan. Thus, it has only trained the indigenous Afghan forces.

Turkey has formed Turkish Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs) led by civilians. These PRTs enforced judicial procedures, built infrastructure, initiated projects for health and education, improved the quality of life for the local population, etc. The first PRT was established in Wardak province in November 2006. The former governor of Wardak said that the Turks work within Afghan culture and values; thus, their programs are happily accepted. Another operational PRT team was formed in July 2010 in Jawzjan province.

Turkey carried out a sustainable assistance program for Afghanistan in cooperation with the Turkish International Cooperation Agency (TIKA), the Foreign Ministry, and the Turkish General Staff. This was a comprehensive program to assist educational and health projects. On one side, Turkey abstained from troops surge in Afghanistan, while on the other side, it launched its assistance programs to reconstruct the war-torn state.

A Diplomatic Approach to a Peaceful Afghanistan

Turkey pursued active diplomacy to tackle the worsened scenario in Afghanistan. Recognizing the geopolitical reality, Turkey strengthened its ties with Pakistan for bringing stability to the region and establishing a peaceful Afghanistan. In 2009, Davutoglu phrased that both countries had historical, permanent, and strategic ties.21 Both states cantered for economic cooperation, cultural exchange, and security solutions. Turkey, Afghanistan, and Pakistan held trilateral meetings. The Turks have always vowed complementary and interlocking regional programs.

Turkey launched regional collaboration programs to tackle the situation in Afghanistan. The Istanbul Process or Heart of Asia conference was one such effort. This conference was attended by the state heads and ministers of the regional states. Before this conference, a regional summit was held in 2009 in Istanbul.

Turkey wanted a well-coordinated framework to tackle terrorism, extremism, and drug trafficking. Under this framework, regional partners established a mind platform to improve regional dialogue, security, and cooperation.22 At the London conference, the former Afghan president, Hamid Karzai, paid his gratitude to Turkey for its trilateral and regional efforts.

From the above discussion, one can conclude that Turkey was eager to be a significant factor, and its diplomatic adventures were crucial in developing regional cooperation. Turkey’s role in Afghanistan cannot be underestimated. Turkey has the potential to reconstruct Afghanistan; its vision was always one of a broad regional consensus of the states to help Afghanistan.

5. Central Asian Republics

Central Asian states have the most to lose when it comes to Afghanistan. Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan were the most willing and able states when it comes to making Afghanistan peaceful. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan remained at the far end while Turkmenistan played a mediocre role.23 These Central Asian states have three concerns—war spillover, terrorism, and narcotics. Their policy response was usually in three broad strategies—defense, development, and diplomacy. They have maintained a military buffer zone, contributed via socio-economic development, and expedited a negotiated peace process.24

Kazakhstan’s Campaign in Afghanistan

Kazakhstan always wanted to create a model of a regional zone of peace and security. It ensured Russia and Iran in 2010 that there would be no US military presence in Kazakhstan. It adopted the Nazarbhaev codex. This code included preventive diplomacy, prophylactic work with the youth, disruption of terror financing, intelligence sharing, and economic development.25 It spent a few million dollars under the banner of humanitarian projects.

Kazakhstan adopted the law of official development assistance in 2014, which sought to elevate women’s rights and economic independence in Afghanistan, making it more peaceful. It introduced an education program in 2010, which amounted to 50 million US dollars, but did not produce any practical result. This project got repackaged in the form of the 2018 Astana Initiative.

Kazakhstan’s foreign direct investment in Afghanistan, from 2005 to 2017, remained 300 thousand US dollars. It tends to maintain the security architecture of Russia and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO). In 2018, Kazakhstan held the CSTO’s chair and participated in military drills.

Uzbekistan: Reaping Economic Benefits

Uzbekistan has focused on regional security and regionalization. Tensions prevailed from 2005 till 2017 between the US and Uzbekistan. After the 2005 Andijan massacre, Uzbeks closed the American base. In 2018, the Jaihun military exercise was carried out with Tajikistan. Uzbekistan acted as a mediator between the great powers. It resumed participation in counter-terror exercises with Russia and Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) in 2018.

To minimize state crimes against pious Muslims, Uzbekistan refurbished its National Security Service. Its new name is “State Security Service”.25 This act was to discourage ISIS and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and de-legitimize their actions. But the whole idea of Uzbekistan about a peaceful Afghanistan spun around two things, how to subside the Afghan threat and economic jackpots.

For Afghanistan to be peaceful, dialogue appeared as the most plausible option in the Tashkent conference and in the other peace initiatives. Uzbekistan’s foreign minister met with the Taliban’s representative in 2018. This meeting was crucial as it increased the Taliban’s legitimacy and urged on the plan that dialogue is the only option left for a peaceful Afghanistan.

Economically speaking, Tashkent saw TAPI (the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India Pipeline) and CASA-1000 as economic opportunities but mainly focused on smaller projects funded by external agencies like World Bank or the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Kyrgyzstan Main Concern

Kyrgyzstan followed the footsteps of the other Central Asian Republics, whether in terms of economic engagement, military actions, or diplomatic runs. Bishkek does not have the desire or capacity to improve relations with Kabul. Seeing the inherent value for itself, Kyrgyzstan invested in upgrading the Andijan-Osh-Kashgar automobile corridor, ignoring the reality check that it would have very little meaning for Afghanistan. The same was the case with a railway built by China connecting Kyrgyzstan with China and Uzbekistan.

Kyrgyzstan saw ISIS as the single most perilous threat which would jeopardize sustainable development in Central Asia. At a point, Kyrgyzstan was in talks with Russia about a new Russian military base. Former Kyrgyz president, Jeenbekov, gave a wide-ranging interview in May 2018. He highlighted the need for “intergovernmental coordination” in the struggle against challenges and security threats from Afghanistan to the Central Asian states. In the meantime, Bishkek had contemplated a “collective response” displayed during the “Issyk–Kul Anti-terror 2018” military exercise.

Threats to Tajikistan

Tajikistan is primarily apprehensive of the situation in Afghanistan. Its response throughout the last two decades remained agitated. Tajikistan signed a defense pact with Russia worth 122 million US dollars in weapon sales in 2018. Russia also reinforced its 201st base to protect Tajikistan. The country is mainly worried about war spillover, drug trafficking, smuggling, and ISIS presence on Afghan soil.

Tajikistan faces major issues to halt cross-border drug trafficking, despite enough border patrols (however 4.6 times lesser than that of Pakistan). Tajikistan had clashes with the Afghan administration over the issue of border administration. Realistically speaking, the Tajik military didn’t have enough capacity for satisfying border management. There may be a considerable amount of exaggeration in the claims, but the Tajik military struggled to keep its face and not lose at the hands of its rivals.

Tajikistan was at the crossroads of NDN (Northern Defence Network). Thanks to this project, mobility, and infrastructure improved in Afghanistan to some limits. Other measures remained either static or plummeted. Tajikistan, however, follows the strategy of Development-Security Nexus.

Turkmenistan’s Neutrality

As far as Turkmenistan is concerned, it has primarily declared state neutrality. In April 2018, President Gurbanguly Berdimuhammedov reiterated his state’s neutrality, suggesting that Ashgabat could provide a valuable forum for progressing talks for a peaceful Afghanistan. Turkmenistan maintained its legacy of self-isolation. The leadership of the most reclusive Central Asian republic abstained from passing a value judgment on the performance and future of the central government in Kabul.

It sent a low-level representative to the Tashkent conference, did not participate in any military exercises in the region, and refrained from the wholehearted endorsement of any new initiatives supporting a peaceful Afghanistan. Turkmenistan is highly obsessed with the TAPI megaproject, which has been suffering for a long time now. Turkmenistan issued its official foreign policy journal, which cited that the international community must support TAPI financially as it is highly beneficial for Afghanistan. It would help Afghanistan overcome regress and stagnation.

It also argued that the future of Afghanistan is reliant on the involvement of external agential as well as structural involvement but TAPI is equally important to Turkmenistan. “TAPI is a project for regime stability; it’s not a socially constructed artifact,” said Luca Anceschi. The internal dynamics of Turkmenistan have been worrying the Central Asian Republics and Russia.

Conclusion

Analyzing the above data, it can be concluded that the regional actors were keener on pursuing their interests in Afghanistan. Their efforts were significant in the context that they served them the stability they wanted for their ambitions. Pakistan wanted to devise a power-sharing formula including the Taliban in the equation. China feared war spillover and terrorism in Xinjiang. It also wanted to keep the US busy in Afghanistan.

Iran wanted to push its enemy, the US, out of the region; however, it was initially aligned with it in 2001 on the fact that the Taliban should be dethroned. Turkey was seeking a bigger role in the Islamic world and international politics, and it was also a part of NATO. The Central Asian Republics strived for survival and increasing their importance in international politics, and they wanted to export the resources they have. All of their efforts were interest-based and motivated by the geopolitical compulsions they face.

Endnotes

- Mustafa Nawaz Khokhar, “Playground of Empires,” The News International, August 31, 2021. https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/885614-playground-of-empires.

- Ayesha Zafar,”Pakistan Hosts the 2021 OIC Meeting on Afghanistan,” Paradigm Shift, 2021. https://www.paradigmshift.com.pk/oic-meeting-pakistan/

- Kirill Nourzhanov and Amin Saikal, The Spectre of Afghanistan: Security in Central Asia (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021).

- “Pakistan Our Twin Brother, India A Friend: Karzai,” Hindustan Times, October 5, 2011. https://www.hindustantimes.com/world/india-is-friend-pak-twin-brother-karzai/story-IZsYwindRKBWGTsrQlk1ZN.html

- Michael E. O’Hanlo, “A Deadly Triangle Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India,” Brookings, 2013. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2013/07/03/hope-in-a-deadly-triangle-of-afghanistan-pakistan-and-india/

- Henry Kissinger, “Henry Kissinger on Why America Failed in Afghanistan,” The Economist, 2021. https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2021/08/25/henry-kissinger-on-why-america-failed-in-afghanistan.

- Amina Khan, “Prospects of Peace in Afghanistan,” Strategic Studies 36, no. 1 (2016): 18–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48535932.

- Shawn Snow, “Ghani’s Deal with the Devil: Hekmatyar and Transitional Justice,” The Diplomat, September 22, 2016. https://thediplomat.com/2016/09/ghanis-deal-with-the-devil-hekmatyar-and-transitional-justice/.

- Zainab Riaz, “From the American Invasion of Afghanistan to Taliban 2.0,” Paradigm Shift, 2021. https://www.paradigmshift.com.pk/american-invasion-of-afghanistan/.

- Kate Clark, “Flash from the Past: The 2002 Tokyo Conference – The World’s Most Difficult Story,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, March 9, 2020. https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/economy-development-environment/flash-from-the-past-the-2002-tokyo-conference-the-worlds-most-difficult-story/.

- APP, “Pakistan’s Development Assistance to Afghanistan Reaches 1 Billion US$: Envoy,” The Nation, June 15, 2018. https://nation.com.pk/15-Jun-2018/pakistan-s-development-assistance-to-afghanistan-reaches-1-billion-us-envoy.

- Jason Li, “China’s Conflict Mediation in Afghanistan,” Stimson, 2021. https://www.stimson.org/2021/chinas-conflict-mediation-in-afghanistan/

- Al Jazeera, “Chinese Officials and Taliban Meet, in Sign of Warming Ties,” July 28, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/7/28/chinese-officials-taliban-vow-warm-ties-in-meeting.

- James Dobbins, “Engaging Iran,” The Iran Primer, October 11, 2010. https://iranprimer.usip.org/resource/engaging-iran

- Louis Charbonneau, “Iran Says Its Aid to Afghanistan Totals $500 Million,” Reuters, November 4, 2010. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-iran-idUSTRE6A34PN20101104

- “Donors Meet in Tokyo to Commit to Major Recovery Plan for Conflict-Ravaged Afghanistan,” United Nations, January 18, 2002. https://www.un.org/press/en/2002/afg181.doc.htm.

- Mohsen M. Milani, “Iran’s Policy Towards Afghanistan.” Middle East Journal 60, no. 2 (2006): 235–56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4330248.

- Sudha Ramachandran, “India’s Controversial Afghanistan Dams,” The Diplomat, February 5, 2020. https://thediplomat.com/2018/08/indias-controversial-afghanistan-dams/

- Salih Dogan, “Turkey’s Presence and Importance in Afghanistan,” USAK Yearbook of International Politics and Law 4, 2011.

- Murat Yeşiltaş and Ali Balcı, “A Dictionary of Turkish Foreign Policy in the AK Party Era: A Conceptual Map,” Center for Strategic Research (SAM), 2013. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep05083

- Richard Ghiasy and Maihan Saeedi, “The Heart of Asia Process at a Juncture: An Analysis of Impediments to Further Progress,” 2014.

- Kirill Nourzhanov and Amin Saikal, The Spectre of Afghanistan: Security in Central Asia (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021).

- Ibid.

- Malika Orazgaliyeva, “Kazakhstan Launches First ODA Project in Afghanistan, with Support from UNDP and Japan,” Astana Times, 23 February 2017 https://astanatimes.com/2017/02/kazakhstan-launches-first-oda-project-in-afghanistan-with-support-from-undp-and-japan/

- Timur Toktonaliev and Turonbek Kozokov, “Uzbek President Reins in Security Service,” IWPR, 4 April 2018, https://iwpr.net/global-voices/uzbek-president-reins-security-service

Bibliography

- Al Jazeera. “Chinese Officials and Taliban Meet, in Sign of Warming Ties.” July 28, 2021. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/7/28/chinese-officials-taliban-vow-warm-ties-in-meeting.

- APP. “Pakistan’s Development Assistance to Afghanistan Reaches 1 Billion US$: Envoy.” The Nation. June 15, 2018. https://nation.com.pk/15-Jun-2018/pakistan-s-development-assistance-to-afghanistan-reaches-1-billion-us-envoy.

- Charbonneau, Louis. “Iran Says Its Aid to Afghanistan Totals $500 Million.” Reuters. November 4, 2010. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-afghanistan-iran-idUSTRE6A34PN20101104

- Clark, Kate. “Flash from the Past: The 2002 Tokyo Conference – The World’s Most Difficult Story.” Afghanistan Analysts Network, March 9, 2020. https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/economy-development-environment/flash-from-the-past-the-2002-tokyo-conference-the-worlds-most-difficult-story/.

- Dobbins, James. “Engaging Iran.” The Iran Primer. October 11, 2010. https://iranprimer.usip.org/resource/engaging-iran

- “Donors Meet in Tokyo to Commit to Major Recovery Plan for Conflict-Ravaged Afghanistan.” United Nations. January 18, 2002. https://www.un.org/press/en/2002/afg181.doc.htm.

- Ghiasy, Richard, and Maihan Saeedi. “The Heart of Asia Process at a Juncture: An Analysis of Impediments to Further Progress.” 2014.

- Khan, Amina. “Prospects of Peace in Afghanistan.” Strategic Studies 36, no. 1 (2016): 18–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48535932.

- Khokhar, Mustafa Nawaz. “Playground of Empires.” The News International. August 31, 2021. https://www.thenews.com.pk/print/885614-playground-of-empires.

- Kissinger, Henry. “Henry Kissinger on Why America Failed in Afghanistan.” The Economist. 2021. https://www.economist.com/by-invitation/2021/08/25/henry-kissinger-on-why-america-failed-in-afghanistan.

- Li, Jason. “China’s Conflict Mediation in Afghanistan.” Stimson. 2021. https://www.stimson.org/2021/chinas-conflict-mediation-in-afghanistan/

- M. Milani, Mohsen. “Iran’s Policy Towards Afghanistan.” Middle East Journal 60, no. 2 (2006): 235–56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4330248.

- Zafar, Ayesha. “Pakistan Hosts the 2021 OIC Meeting on Afghanistan.” Paradigm Shift. 2021. https://www.paradigmshift.com.pk/oic-meeting-pakistan/

- Nourzhanov, Kirill, and Amin Saikal. The Spectre of Afghanistan: Security in Central Asia. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2021.

- O’Hanlon, Michael E. “A Deadly Triangle Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India.” Brookings. 2013. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2013/07/03/hope-in-a-deadly-triangle-of-afghanistan-pakistan-and-india/

- Orazgaliyeva, Malika. “Kazakhstan Launches First ODA Project in Afghanistan, with Support from UNDP and Japan.” Astana Times. 23 February 2017 https://astanatimes.com/2017/02/kazakhstan-launches-first-oda-project-in-afghanistan-with-support-from-undp-and-japan/

- “Pakistan Our Twin Brother, India A Friend: Karzai.” Hindustan Times. October 5, 2011. https://www.hindustantimes.com/world/india-is-friend-pak-twin-brother-karzai/story-IZsYwindRKBWGTsrQlk1ZN.html

- Ramachandran, Sudha. “India’s Controversial Afghanistan Dams.” The Diplomat. February 5, 2020. https://thediplomat.com/2018/08/indias-controversial-afghanistan-dams/

- Riaz, Zainab. “From the American Invasion of Afghanistan to Taliban 2.0.” Paradigm Shift. 2021. https://www.paradigmshift.com.pk/american-invasion-of-afghanistan/.

- Salih Dogan. “Turkey’s Presence and Importance in Afghanistan.” USAK Yearbook of International Politics and Law 4 (2011).

- Snow, Shawn. “Ghani’s Deal with the Devil: Hekmatyar and Transitional Justice.” The Diplomat. September 22, 2016. https://thediplomat.com/2016/09/ghanis-deal-with-the-devil-hekmatyar-and-transitional-justice/.

- Toktonaliev, Timur, and Turonbek Kozokov. “Uzbek President Reins in Security Service.” IWPR. 4 April 2018. https://iwpr.net/global-voices/uzbek-president-reins-security-service

- Yeşiltaş, Murat, and Ali Balcı. “A Dictionary of Turkish Foreign Policy in the AK Party Era: A Conceptual Map.” Center for Strategic Research (SAM). 2013. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep05083

If you want to submit your articles, research papers, and book reviews, please check the Submissions page.

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.