Abstract

Groundwater, often called “liquid gold,” is rapidly depleting due to the pressures of urbanization and industrialization. The situation is further worsened by the actions of a tanker mafia operating in several cities across Pakistan and India. These operators exploit water scarcity for profit and, in doing so, aggravate the overall water crisis. This research analyses the role of the tanker mafia in exploiting groundwater in the cities of Karachi, Islamabad, Mumbai, and New Delhi. It focuses on how these illegal operations worsen water scarcity and disrupt urban water management systems.

Using elite theory as its framework, the study explores how powerful elites in Pakistan and India exploit both public populations and natural resources. Based on a qualitative analysis of secondary data, the study underscores the urgent need for policy reforms such as stricter groundwater use regulations, increased investment in sustainable infrastructure, and the promotion of community-based water management solutions. Addressing these challenges requires collaborative efforts to dismantle inequities and ensure sustainable water governance in these rapidly urbanizing cities.

Introduction

Clean, safe, and adequate access to water is a fundamental right of every individual. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 focuses on ensuring the availability and management of water and sanitation for all (Everything about the Sustainable Development Goal 6). However, rapid urbanization and industrialization have left many regions facing unprecedented water crises. With overpopulation, access to water in highly urbanized cities becomes increasingly challenging. Urban water scarcity in South Asia, particularly in the most populated cities of Pakistan and India, is growing.

Water scarcity impacts water availability and threatens political stability, economic growth, and long-term public health. Scarcity drives the over-extraction of groundwater to meet demands. In India and Pakistan, most water is used for agriculture, while domestic needs play a comparatively minor role. Rapid urbanization and population growth have intensified water demands, particularly in Karachi, Islamabad, Mumbai, and New Delhi.

The main issue is that groundwater is considered the property of the landowner on whose land it is found. Thus, it can be exploited at the discretion of the landowner. The absence of laws to regulate groundwater extraction poses a significant threat to the water table. The BGS report states, “Pakistan and India have some of the most exploited groundwater systems on the Earth”(Press, 2022). Moreover, water is a necessity that people require at all costs.

When the government fails to supply it, they seek alternatives. The situation is worsened by the unregulated and informal water tanker industry. The water tanker mafia exists in places where there is an inadequate municipal water supply system. This exploitation manifests in the overcharging for water, a practice that further drives the over-extraction of groundwater and exacerbates the scarcity problem. The term “tanker mafia” refers to organized groups that operate water tankers by diverting water from state-run freshwater pipelines, groundwater aquifers, and open water bodies (Yousuf Sajjad, 2019).

Despite strong advocacy for water billing, where residents of Lohi Bher, Islamabad, pay monthly fees for water supply and security services, they often remain deprived of these essential services (Sulaiman, 2020). The lack of planning, inadequate water management infrastructure, and failure to address the issue significantly contribute to the proliferation of such mafias. This research analyses the impacts of groundwater over-extraction and government failures within informal systems. It also proposes alternative solutions to reduce reliance on tanker mafias. The study is guided by the following research questions:

- How do tanker mafias exploit groundwater in Pakistan and India?

- To what extent do governance failures contribute to the proliferation of tanker mafias?

- What alternative water supply systems can mitigate the reliance on tanker mafias?

Literature Review

Groundwater exploitation by tanker water markets (TWMs) has emerged as a key issue in the urban areas of Pakistan and India (Zozmann, 2022). Urban and peri-urban populations in Pakistan depend on informal tanker water markets (Rana, 2024). Islamabad, the capital of Pakistan, suffers from an urban water crisis due to the depletion of the groundwater level (Sulaiman, 2020). The article “Investigating Corruption and Tanker Mafias in Karachi’s Water Supply Chain” highlights systematic corruption in Karachi’s water distribution network, offering insight into the dynamics of groundwater exploitation (Maher, 2024).

Groundwater exploitation and the rise of tanker mafias is a regular phenomenon in the metropolitan and large urban centers of states like India. Delhi, Bangalore, Chennai, and Mumbai are all suffering from this issue. Water is a prominent theme in Delhi’s Politics (Birkinshaw, 2018). Groundwater exploitation in Pakistan has reached unsustainable levels, posing significant challenges for urban water management. Urban centers are facing water scarcity and will eventually fall prey to water cartels (Rehman, 2023).

TWMs operate in areas where public water infrastructure is not working properly (Zozmann, 2022). The literature highlights that water scarcity in urban areas, due to over-population and less public investment in water infrastructure, and politicization of water leads to the propagation of these markets (Birkinshaw, 2018). TWMs provide water for residential and industrial consumers in cities like Karachi, Bangalore, and Delhi (Zozmann, 2022; Sulaiman, 2020). The literature sheds light on the unsustainable practices carried out by tanker mafias, which pose severe ecological and health challenges, including aquifer depletion and contamination (Birkinshaw 2018).

In Lohi Bher Islamabad, the groundwater levels have fallen from 40 meters to over 150 meters within a short span of 10 years (Sulaiman, 2020). In Pakistan, the groundwater level is dropping drastically; the per capita availability of surface water has plummeted from 5,260 cubic meters in 1951 to 900 cubic meters by 2023 (Rehman, 2023). Studies in Karachi and Chennai indicate that unregulated water extraction exacerbates the regional water crisis and accelerates the decline of the water table (Zozmann 2022). The malpractice of these water cartels has posed not only serious ecological and health risks but also economic and governance risks to both the residents and ruling governments (Rana, 2024).

Residents struggle daily to access clean drinking water. Despite being willing to pay for public water supply or piped systems, they are exploited by tanker mafias due to poor governance and the politicization of water (Sulaiman 2020). These dynamics of the informal water economy were studied in Sangam Vihar, Delhi. Many unauthorized colonies, excluded from municipal water systems, exist there and the government has failed to regulate them due to political involvement. These informal settlements heavily rely on tanker water mafias, utilize unregulated borewells, and operate within informal governance networks, which ultimately leave them vulnerable to exploitation. However, these markets are not affordable for each stratum of society (Birkinshaw, 2018).

Moreover, the informal nature of many TWM operators, along with regulatory gaps and unchecked extraction of groundwater, exacerbates the situation (Zozmann, 2022; Rehman, 2023). Corruption and political turmoil have created monopolistic and oligopolistic control over these markets, which, as a result, intensify already existing disparities (Maher, 2024). The absence of stern regulatory frameworks, together with weak enforcement mechanisms, allows tanker operators to monopolize water distribution and charge as per their demands for their profit maximization.

Cities like Islamabad, Karachi, and Lahore have become synonymous with both necessity and opportunism. These mafias also get political patronage (Rana, 2024). The governance challenges linked with the tanker mafia are deeply rooted in the broader context of resource politics and urban informality. Literature reveals that attempts to regulate or integrate informal water networks into formal systems often face resistance due to the political and economic interests of local actors integrated and served through this system (Birkinshaw, 2018).

Literature reveals how the private tanker mafia, with vested interests in government officials, divert water from public utilities to get water profit. This is from meddling with official meters and running illegal hydrants to creating a parallel market propelled by an inequitable conception and institutional oversight (Maher, 2024). The Aam Admi Party in Delhi tried to burst this system but was unable to do so because of a lack of institutional reforms (Birkinshaw, 2018). The informal water economy in both Pakistan and India highlights the blurred boundaries between public and private interests, legality and illegality, and exploitation and governance system failure.

The literature argues that although TWM provides temporally flexible services, it fails to meet the standard and quality of water. In both Pakistan and India, tanker operator associations set prices and limit market entry to maximize profits, imposing a “poverty penalty” on low-income groups (Zozmann, 2022). Resulting in reliance on tanker-supplied water that often poses severe health risks. Inadequate policy planning, climate-induced challenges, and poor infrastructure further exacerbate the crisis, and it calls for urgent but sustainable water management solutions (Rehman, 2023).

The study reveals that residents pay approximately 3000 per month to tanker mafias, even though they would be willing to pay around 140 per month for tap water services. This stark contrast underscores the failure of governance to provide basic facilities and enforce regulations on tanker mafias (Sulaiman, 2020). As urban populations grow, water scarcity will intensify, and reliance on informal sectors will increase. This trend calls for comprehensive water management policies that integrate technological solutions, sustainable groundwater regulations, and active public participation.

Urban populations continue to grow, and reliance on such informal systems intensifies, highlighting the urgent need for comprehensive water management policies (Birkinshaw 2018). These dynamics emphasize the need for integrated water management policies that balance the instant utility of TWMs with long-term sustainability goals, particularly through regulatory reforms, equitable pricing mechanisms, and investments in alternative water sources to reduce dependence on groundwater (Zozmann, 2022).

The existing literature highlights the need for an integrated water management system that addresses the socio-political dynamics of groundwater exploitation. Promotion of community-based management and enforcement of legal constraints on tanker mafia are needed. The research suggested technological interventions, like monitoring water extraction through digital tools and expanding alternative water sources, including rainwater harvesting and surface water treatment (Rana, 2024).

However, attaining these goals requires a participatory governance framework that includes local communities and places in order to have equitable access to water resources. The challenges studied call for corresponding efforts by policymakers, urban planners, and civil society to mitigate the effects of the tanker mafia and ensure sustainable groundwater usage (Zozmann, 2022; Birkinshaw, 2018; Rana, 2024).

The study suggests rainwater harvesting is a promising solution to lessen groundwater depletion and the dominance of tanker mafias. However, investment in infrastructure, awareness campaigns, and policy incentives like subsidies, etc., are required. Additionally, public-private partnerships can be framed to build and develop an equitable water management framework (Rehman, 2023). There is an urgent need for government intervention to regulate the tanker mafia and establish sustainable water management policies. Such measures are vital to alleviate the economic and health impacts of water scarcity and to ensure safe water for all (Sulaiman, 2020).

The existing literature highlights the over-extraction of groundwater by tanker mafias and its long-term effects on water sustainability in Pakistan and India. The studies also investigate the governance failures that played a role in the rise of these mafias. Furthermore, alternative water supply systems, such as rainwater harvesting, are discussed as potential solutions to recharge depleted water tables. However, the existing literature does not offer comprehensive and sustainable solutions. This research aims to address these gaps by proposing some actionable strategies in the discourse.

Theoretical Framework

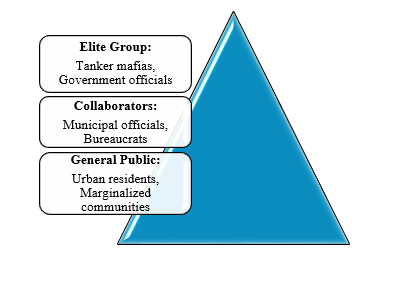

This research is grounded in elite theory, as developed by Gaetano Mosca and Vilfred Pareto, a framework in political science that emphasizes the disproportionate influence of elites on policymaking processes (Maloy, 2025). The theory states that the power is concentrated in the hands of the small, privileged group, exploiting the broader population. In Pakistan and India, the elite theory offers a compelling framework for examining how a small group of powerful individuals and organizations, such as tanker mafias, manipulate resources to serve their own interests.

The tanker mafia, in both countries, consists of wealthy individuals and businesses. These businesses control the supply of water in regions facing urbanization and water scarcity. They violate the existing laws and regulations to monopolize groundwater resources. Under the elite theory, it can be argued that policymaking in both countries is shaped by the interests of these elites, whose neglect often leads to wider public needs. Despite the increasing concern about groundwater depletion, the public policies in both countries tend to prioritize the interests of a few.

Additionally, the elite theory suggests that these mafias maintain their dominance by exerting influence over local governments and leveraging informal networks to navigate bureaucratic and political obstacles. On the other hand, government agencies often lack the resources, capacity, or political will to confront their proliferation. Thus, applying the lens of elite theory, the issue of groundwater exploitation in Pakistan and India provides a deeper insight into the interests of the tanker mafia and other elites that shape public policy.

Methodology

The research has adopted a qualitative approach, relying on secondary sources to explore the issue of groundwater exploitation by tanker mafias in Pakistan and India. Data has been gathered from a range of sources, including academic literature, government reports, news articles, and research papers. The sources were selected based on their relevance to the research questions and their ability to represent both Pakistan and India.

This research employs comparative analysis to highlight the similarities and differences in the operations of tanker mafias in Pakistan and India. Contextualizing these findings within theoretical frameworks will provide deeper insights into the systematic nature of the issue. Ethical considerations include the proper citation of all secondary sources and the acknowledgment of the limitations of relying solely on secondary sources.

The research aims to comprehensively understand tanker mafias’ role in groundwater exploitation, identify the governance gaps, and propose actionable policy recommendations for sustainable water management in urban areas. This research relies on articles, journals, and research papers for data, as no books addressing the issue of prevailing tanker mafias were found.

Findings and Analysis

A detailed analysis of the literature reveals that water resources are heavily exploited in both India and Pakistan, particularly in urban areas such as Mumbai, Karachi, Islamabad, and New Delhi. The essential commodity, often referred to as “liquid gold,” is being exploited by the tanker mafia, with the government fully aware of this practice. In addition to being exploited, the water supplied by the tanker mafia is often of poor quality and unsafe for drinking, leading to various health problems. The following are the findings derived from the study of the literature.

Groundwater and Tanker Mafia Activities

According to Worldometer’s 2025 estimate, India and Pakistan together account for about 20.9% of the world’s population. To meet rising demands, groundwater is extensively extracted (Worldometer, 2025). However, this practice often results in the contamination of water sources due to the lack of proper infrastructure. As demand rises in urban areas, illegal extraction exacerbates water stress. Moreover, water in these regions is essential not only for domestic use but also for agriculture.

Pakistan is a federal state, and the 18th Amendment to its Constitution (1973) has granted provinces the authority to regulate water issues within their jurisdictions. In contrast, India, comprising 28 states, grants jurisdiction over its rivers to these states, with local governments managing water distribution. Another common issue between both countries is the over-exploitation of water in urban cities, driven by the involvement of various tanker mafias. Furthermore, the tanker mafias in each country operate independently and employ different methods.

The tanker mafia operates differently in various Pakistani cities, such as Karachi and Islamabad. Karachi, located on the country’s coastline, is severely water-stressed; the city requires at least 70 million gallons per day to meet demand (Editorial, 2025). The problem is rooted in a dysfunctional water distribution system caused by state negligence. Consequently, while water is distributed to only half of the population, the remaining residents must rely on illegally operating tanker mafias (Fioriti & Wahlha, 2021).

In contrast, the tanker mafia in Islamabad exploits the population using a different method. Over the last decade, groundwater levels in Lohi Bher have decreased from 40m to 150m. Here, residential societies supply water in exchange for a monthly bill; however, on average, households pay approximately Rs. 3000 per month while still facing an insufficient supply. This forces residents to rely on local water tankers, with the mafia exploiting users by over-extracting from aquifers, charging extra fees, and delivering an inadequate supply.

India is one of the largest users of groundwater, yet it holds only about 4% of the world’s total. The country allocates 60% of its water for irrigation and 40% for domestic purposes, although this domestic allotment is considered insufficient to meet growing demand (Shiferaw, 2021). In cities like New Delhi and Mumbai, rapid urbanization has outstripped the capacity of public water systems, resulting in high dependency on groundwater.

Additionally, local governments face challenges in providing a consistent water supply due to limited availability. This situation creates an opportunity for the tanker mafia to exploit the population by offering a private water supply. In 2014, the Government of India reported that nearly three-fourths of Delhi’s underground aquifers are over-exploited by tanker mafias. Despite various initiatives to curb illegal water pumping and sales, efforts have been unsuccessful.

In India, the tanker mafia operates in an unorganized, fragmented manner, making it difficult to eliminate by targeting only the major players (Sethi, 2025). In Mumbai, there are two distinct groups of water tanker operators. One group illicitly steals water from council pipelines and the local distribution system, while the other supplies water, often with government sponsorship, to meet demand. The first group is referred to as the “tanker mafia,” whereas the second is known as “legitimate water suppliers” (Kearnan, 2019).

In both cases, groundwater is being exploited to fulfill the demands. Water is not only essential for domestic use but also crucial for drinking and food-related needs. The situation is worsened by the tanker mafias, who extract water without any regulations, primarily by over-extracting beyond the set limit. Typically, the groundwater is recharged by rain, but excessive extraction beyond the limit fails to address the issue.

According to the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), Delhi’s groundwater extraction rate has reached 100.77%. The capital’s groundwater recharge was recorded at 34,190.47 cubic hectares meters, but approximately 34,453.58 cubic hectares were extracted (Gandhiok, 2025). In the case of Mumbai, the over-extraction of water may result in salination and contamination of groundwater from the coast. The CGWB has warned that by 2025, Mumbai’s water availability per person will be reduced to just 25% (Tembekar, 2018). The detailed extraction of groundwater for Islamabad is not available. Karachi faces a similar problem to Mumbai, with the city extracting 550 to 600 million gallons of water per day (Fazal, 2023). The situation is alarming and requires the authorities’ immediate attention and action.

Governance Challenges in Tanker Mafia Growth

Governance failures in both countries have significantly contributed to the proliferation of tanker mafias. Weak enforcement, regulatory loopholes, and institutional corruption create an environment in which these illegal operators can thrive. Moreover, poor infrastructure development, especially in urban areas, forces communities to depend on alternative water sources, which are then exploited by these mafias.

In Karachi, the water supply infrastructure is outdated, costly, and inadequate. The existing technology is wasteful, rendering the city vulnerable to system failures. Although the Karachi Water and Sewerage Board (KWSB) is responsible for water distribution, the government’s inability to provide a consistent supply has allowed the tanker mafia to expand its influence. These groups have transformed a public resource into a profit enterprise, controlling access and selling water at excessively high prices (Editorial, 2025). Moreover, Karachi’s century-old pipeline network is insufficient to meet the current demand. In response, the government encouraged private tanker associations to refill at hydrants and help meet the city’s water needs.

Initially, the association was allowed to operate for two years, but it later flourished due to the government’s inefficiency in keeping it under control (Maher, 2024). The mafia has spread so extensively that it has become dangerous for researchers to expose them. Additionally, it has been observed that the water tanker mafia is extracting water daily without any limitations daily. The investigations carried out by Dawn Investigations revealed, “The government functionaries, KWSB personnel, military personnel, hydrant contractors, tanker owners, police, Rangers, community-level strongmen, and political workers all are part of this mafia” (Naziha Syed Ali, Aslam Shah, 2023).

In Islamabad, water supply is managed by the Water and Power Development Authority (WAPDA), with local society administrations further regulating distribution. Although water is supplied daily to households, enabling residents to fill their tanks, financial corruption among society leaders often results in WAPDA cutting off water meters and halting the supply. Consequently, residents are forced to rely on local private tanker associations, which not only overcharge but also provide poor-quality water. In 2024, the price for approximately 300 gallons of water supplied by the tanker mafia rose to Rs. 2200, double the original rate of Rs. 1100. Although society leaders raised concerns about this problem, no effective solution was reached.

The situation in India is different from Pakistan. In the city of Delhi, the tanker mafia results from a neglected and corrupted water system of the Delhi Jal Board (DJB). Water is obtained from the borehole operators at a set cost. The minimum order required for the tanker water is 1050 gallons. The mafia in the city exploits the poor, as they are unable to get it. Delhi was initially an agricultural city back in the 1960s. However, the town went up for urbanization within 20 years. This resulted in the authorized and unauthorized formation of colonies.

The city was divided into certain classes, and the elite societies feared that the further spread of the societies would lead to a scarcity of resources, mainly water. Thus, the Common Cause filed a case in 1993 against illegal colonies in the Delhi High Court. It took eight years to announce the verdict. In the meantime, the colonies took the matter into their own hands and dug out borewells and water pumps to draw out groundwater. The DJB drilled a series of boreholes in the city where water was released for eight hours. The private tankers were also allowed to supply drinking water. However, the residents had to wait in queues to get the water from the borewells.

Thus, the tanker association in 2005 connected their pipeline system to the homes of the residents who were willing to pay monthly fees. On the other hand, some residents dug out their own to connect to the pipelines. Thus, the tanker mafia was created. The association initially created by the DJB to provide water as a necessity free of charge to households has now started operating as a business, generating profits. The audits in 2013 found that the colonies get 1 gallon per person of water per day; however, the residents of Central Delhi, which is home to politicians, judges, and other elites, get 116 gallons (Sethi, 2025).

In Mumbai, water has also become a major business. As previously noted, there are two types of tanker associations: one that is “legitimate” and controlled by the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), and another run by private operators, the so-called tanker mafia. Despite the operation of these groups, the city faces severe water scarcity; even the seven dams that supply the city are insufficient. Water is pumped through these tanker networks into the underground tanks of apartments and buildings, although analysts contend that the tanker mafia is closely linked to government interests (Kearnan, 2019).

The case studies from Pakistan and India reveal both similarities and differences in how water is managed and exploited. In Karachi, Mumbai, and Delhi, government failures have paved the way for the proliferation of tanker mafias, with vast urban areas even witnessing the rise of illegal colonies. The direct involvement of government entities in the illegal water supply raises serious governance concerns. Conversely, in Islamabad, financial corruption among society leaders and the government’s lack of proactive intervention exacerbate the situation. Regardless of the differences, the central issues remain: ensuring public access to this essential resource and preventing the depletion of groundwater. Ultimately, despite mounting costs and exploitation, citizens in Karachi, Mumbai, New Delhi, and Islamabad continue to rely on water for their daily needs.

Recommendations

Pakistan and India must adopt alternative strategies that recharge groundwater and ensure equitable water access for all citizens. The governments of both nations should be held accountable for addressing water-related issues. As water-stressed countries, they are particularly vulnerable to water-related disasters. Reducing reliance on tanker mafias in Karachi, Islamabad, New Delhi, and Mumbai necessitates the implementation of alternative water supply systems. Consequently, a collaborative and comprehensive approach is essential to tackle these challenges.

Alternative Water Supply Systems

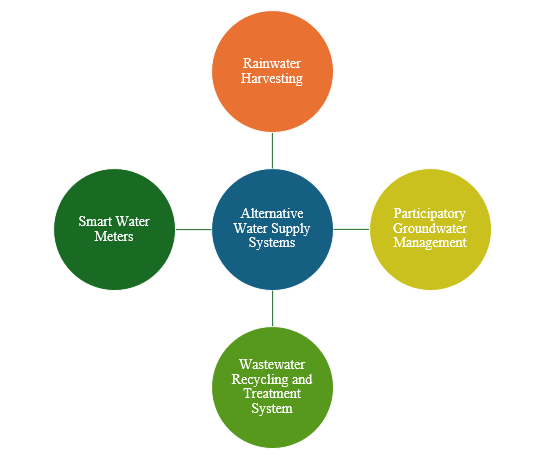

One way to reduce reliance on tanker mafias is through rainwater harvesting. This system not only provides a sustainable, cost-effective alternative for obtaining clean drinking water but also helps mitigate waste by capturing rainwater that would otherwise be lost. Rainwater is collected from runoff via structured systems, water is gathered in gutters, channeled through downspouts, and directed into storage vessels (‘Rainwater Harvesting 101, 2024).

Since both Pakistan and India receive most of their water during the monsoon season, storing this rainwater at the municipal or community level can significantly contribute to addressing water crises. Additionally, this strategy mitigates flooding in low-lying regions, reduces dependence on well water, and eventually aids in restoring groundwater levels. Governments can further support this initiative by offering tax subsidies to households that invest in such a system (Rehman, 2023). Mandatory rainwater harvesting systems for new constructions can alleviate water scarcity and reduce reliance on illegal water suppliers in the populated cities of Karachi, Islamabad, New Delhi, and Mumbai (Majumder, 2015).

Participatory Groundwater Management (PGM) is another effective approach. It empowers communities within a specific aquifer area by granting them governance rights, raising social awareness, and equipping them with the knowledge necessary for effective regulation and implementation. Strengthening community participation in groundwater governance can thus significantly improve management (Shiferaw, 2021).

Wastewater Recycling and Treatment can also be used at the community level, particularly in the cities of Karachi and New Delhi. These systems are cost-effective and can be incrementally upgraded to meet increasing demand or stricter quality standards. The successful implementation of this approach has been carried out in Brazil at the community level by the Environmental Institute (OIA). The system can recycle toxic sewage water into biofuel and clean water, which can be used for domestic purposes (The Environmental Institute, 2024).

Additionally, installing smart water meters through public-private partnerships can empower local communities to report irregularities and reduce the influence of tanker mafias. These smart meters can also monitor changes in groundwater levels, aiding in more effective water resource management.

Mitigating the Governance Challenges

The governance challenge is one of the key barriers to regulating groundwater and preventing its exploitation by tanker mafias in both countries. The involvement of the government and law enforcement agencies in the matter further exacerbates the situation. With transparency and accountability within the governance, certain reforms within institutions, structures, and legal frameworks can mitigate the influence of these mafias.

Pakistan’s National Water Policy of 2018 is its first comprehensive framework addressing both surface and groundwater management, emphasizing efficient resource utilization, especially in areas highly dependent on groundwater. The policy outlines plans for constructing additional storage facilities and rehabilitating existing infrastructure (The Government of Pakistan, 2018). Although it stresses licensing and monitoring for groundwater extraction, inconsistent enforcement, particularly at the provincial level, remains a challenge. Strengthening capacity within state and provincial institutions is therefore essential for effective implementation.

On the other hand, India has several policies and regulations that address the sustainable use and over-extraction of groundwater. The National Water Policy of 2012 deals with sustainable use, water conservation, extraction, and water recharge of both surface and groundwater (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). The National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) and the Central Ground Water Authority (CGWA) are responsible for regulating groundwater. Certain policies and authorities in India deal with the state level. DJB has worked for groundwater recharge, protection, and awareness campaigns. However, in the case of Mumbai, MCGM regulates water supply and extraction.

Despite these regulations, groundwater extraction continues due to weak enforcement and insufficient monitoring. Although appropriate policies exist, their effective implementation requires greater accountability and transparency within government institutions. In several instances, government officials have been implicated in corruption that enables the exploitation of this essential public resource. Moreover, enforcing stricter regulations on groundwater extraction is critical to safeguarding these resources from exploitation by tanker mafias.

Conclusion

In conclusion, due to rising demand and weak governance, groundwater management in Pakistan and India has failed, resulting in severe water shortages. This situation has elevated the tanker mafia to a major stakeholder in an informal water economy. The cities of Karachi, Islamabad, New Delhi, and Mumbai are experiencing a multifaceted crisis, one marked by environmental degradation, socio-economic inequalities, and governance failures. For instance, Karachi and New Delhi, with their high population densities, vividly illustrate the dire consequences of overreliance on groundwater.

In Karachi, where chronic water shortages prevail, the tanker mafia has emerged as a dominant provider, charging exorbitant rates for water. Similarly, in New Delhi, alarming levels of groundwater depletion have compelled informal suppliers to bridge the gap left by failing municipal services. Meanwhile, Mumbai and Islamabad illustrate different facets of the same challenge.

Mumbai’s seasonal monsoons offer only temporary relief, and its structural inefficiencies perpetuate the dominance of tanker mafias—especially in suburban and slum areas- while Islamabad faces a growing reliance on water tankers due to insufficient municipal supply. Addressing these issues requires city-specific yet interconnected solutions with a focus on strengthening municipal water infrastructure and investing in alternative water sources to ensure sustainable water availability.

References

- British Geological Survey (2022, April 22). Hidden from view: A century of rising groundwater levels in India and Pakistan. https://www.bgs.ac.uk/news/hidden-from-view-a-century-of-rising-groundwater-levels-in-india-and-pakistan/

- Editorial. (2025, January 6). Water politics. The Express Tribune. https://tribune.com.pk/story/2520222/water-politics-1

- Everything about the Sustainable Development Goal 6: Clean water and sanitation (n.d.). One Drop Foundation. https://www.onedrop.org/en/news/everything-about-the-sustainable-development-goal-6-clean-water-and-sanitation/

- Fazal, H. (n.d.). Is the shiny new $1.6 billion corporation the answer to Karachi’s water woes? Asia News Network.

- Fiotiti, S. C., & Wahlah, S. (2021, January 12). Focus—Residents of the Pakistani city of Karachi in the grip of the water mafia. France 24. https://www.france24.com/en/tv-shows/focus/20210112-residents-of-pakistani-city-of-karachi-in-grip-of-water-mafia

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (n.d.). National Water Policy 2012. https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC163536/

- Gandhiok, J. (2025, January 6). ‘More groundwater used than recharged’. Hindustan Times. https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/delhi-news/more-groundwater-used-than-recharged-101736187118246.html

- Kearnan, J. (2019, November 3). The Water Mafia of Mumbai. The Water Story. https://thewaterstory.com.au/2019/11/03/the-water-mafia-of-mumbai/

- Maher, M. (2024, February 28). Investigating Corruption and the ‘Tanker Mafias’ in Karachi’s Water Supply Chain. https://gijn.org/stories/investigating-corruption-karachis-water-supply-chain/

- Majumder, S. (2015, July 28). Water mafia: Why Delhi is buying water on the black market. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-33671836

- Naziha Syed Ali, Aslam Shah. (08:30:23+05:00). Dawn Investigations: Selling liquid gold — Karachi’s tanker mafia. Dawn News. https://www.dawn.com/news/1733033

- Rainwater Harvesting 101|Your How-To Collect Rainwater Guide. (2024, December 5). Innovative Water Solutions LLC. https://www.watercache.com/education/rainwater-harvesting-101

- Rehman, Dr. A. (2023, May 3). Breaking The Tanker Mafia’s Grip On Pakistan’s Water Supply. The Friday Times. https://www.thefridaytimes.com/2023/05/03/breaking-tanker-mafias-grip-on-pakistans-water-supply/

- Sethi, A. (2025, January 9). At the Mercy of the Water Mafia. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2015/07/17/at-the-mercy-of-the-water-mafia-india-delhi-tanker-gang-scarcity/

- Sharif, M. H. (2025, January 25). Water shortages in Pakistan: The urgency for water governance. Paradigm Shift. https://www.paradigmshift.com.pk/water-shortages-in-pakistan/

- Shiferaw, B. (2021, August 23). Addressing groundwater depletion: Lessons from India, the world’s largest user of groundwater. https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/blog/addressing-groundwater-depletion-lessons-india-worlds-largest-user-groundwater

- Sulaiman, M. (2020). Economic Burden of Groundwater Shortages and Willingness to Pay for Water Access: A Case Study of Lohi Bher, Islamabad. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics, Islamabad.

- Tembekar, C. (2018, May 9). Tankers are fast depleting Mumbai’s groundwater. The Times of India. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/tankers-are-fast-depleting-mumbais-groundwater/articleshow/64087345.cms

- The Government of Pakistan. (2018). National Water Policy-2018. https://ffc.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/National-Water-Policy-April-2018-FINAL_3.pdf

- Worldometer. (n.d.). Population by Country (2025). https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-country/

- Yousuf Sajjad. (2019, June 3). The water tanker mafia. MSJ Research Projects. https://ir.iba.edu.pk/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1010&context=research-projects-msj

If you want to submit your articles and/or research papers, please visit the Submissions page.

To stay updated with the latest jobs, CSS news, internships, scholarships, and current affairs articles, join our Community Forum!

The views and opinions expressed in this article/paper are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the editorial position of Paradigm Shift.